Kim Kelly in Teen Vogue:

The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to speak out against sexual harassment, and to jumpstart stalled union negotiations. And as we just saw with the Los Angeles teachers’ successful large-scale strike, which spanned six school days, strikers have been winning. Despite the shot of energy that organized strikes have injected into the labor movement, many people aren’t content with run-of-the-mill work stoppages, or even with more militant wildcat strikes.

The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to speak out against sexual harassment, and to jumpstart stalled union negotiations. And as we just saw with the Los Angeles teachers’ successful large-scale strike, which spanned six school days, strikers have been winning. Despite the shot of energy that organized strikes have injected into the labor movement, many people aren’t content with run-of-the-mill work stoppages, or even with more militant wildcat strikes.

As President Donald Trump’s scandal-plagued government shutdown stretches into its fourth week and more than 800,000 federal workers struggle to survive sans paychecks, the words general strike have begun appearing with increasing frequency on social media and in a spate of articles. On January 20, Association of Flight Attendants-CWA President Sara Nelson suggested that a general strike could potentially end the government shutdown. The fact that a labor union official is speaking about such drastic action now is very significant, for one thing because there has not been a major U.S. general strike since the government cracked down on labor following 1946’s Oakland general strike. Also, a general strike is an incredibly massive undertaking; while many organized industry-specific strikes can comprise hundreds or even thousands of workers, a general strike could potentially involve millions.

So what does it all mean? How is a general strike different from a planned, industry-specific work stoppage; why are people interested in the idea now; and what would one look like in 2019?

More here.

HOW LONG did an hour feel in 1971? Was it like three 2018 hours? Ten minutes? The music of the eighty-six-year-old French composer Éliane Radigue forces these questions because as much as it’s about synthesizers and magnetic tape and silence and held notes and resonance, it is also about time. Her work cannot be excerpted or sliced into representative swatches or versified. The movement from a piece’s beginning to its end is the motif itself; to lose even a little of that adventure is to lose the music. Œuvres électroniques (Electronic Works), a new fourteen-CD box set recently released by Ina GRM, collects pieces recorded between 1971 and 2007. The shortest of them is a little over seventeen minutes long; most of them run closer to an hour. These days, Radigue composes largely for acoustic stringed instruments, but she remains as focused an artist as electronic music has ever had, possibly because she never needed the equipment to hear her sound, only a series of tools with which to render it.

HOW LONG did an hour feel in 1971? Was it like three 2018 hours? Ten minutes? The music of the eighty-six-year-old French composer Éliane Radigue forces these questions because as much as it’s about synthesizers and magnetic tape and silence and held notes and resonance, it is also about time. Her work cannot be excerpted or sliced into representative swatches or versified. The movement from a piece’s beginning to its end is the motif itself; to lose even a little of that adventure is to lose the music. Œuvres électroniques (Electronic Works), a new fourteen-CD box set recently released by Ina GRM, collects pieces recorded between 1971 and 2007. The shortest of them is a little over seventeen minutes long; most of them run closer to an hour. These days, Radigue composes largely for acoustic stringed instruments, but she remains as focused an artist as electronic music has ever had, possibly because she never needed the equipment to hear her sound, only a series of tools with which to render it. As the argument has progressed, a de facto alliance between ostensibly progressive identitarians and Wall Street Democrats has come together around asserting, along with Paul Krugman and others, that “horizontal inequality”—i.e., inequality between statistically defined racial/ethnic groups—is a more important problem than “vertical inequality,” characterized as inequality between individuals and households. That distinction instructively makes class and class inequality disappear, which is consistent with the trajectory of American liberalism across the more than seven decades since the end of World War II. Moreover, in a sort of mission creep, opponents of what they decry as a “class-first” position increasingly have come to denounce any expressions of concern for economic inequality as in effect catering to white supremacy. This tendency, which Touré Reed has argued rests on a race-reductionism, has surfaced and spread within the newly revitalized Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), as even many among those who consider themselves socialists object to the organization’s selection of Medicare for All as its key political campaign on the ground that pursuit of decommodified health care for all is objectionable because doing so does not sufficiently center antiracist and anti-disparitarian agendas. I submit that there’s clearly a problem when anti-socialism is defined as socialism.

As the argument has progressed, a de facto alliance between ostensibly progressive identitarians and Wall Street Democrats has come together around asserting, along with Paul Krugman and others, that “horizontal inequality”—i.e., inequality between statistically defined racial/ethnic groups—is a more important problem than “vertical inequality,” characterized as inequality between individuals and households. That distinction instructively makes class and class inequality disappear, which is consistent with the trajectory of American liberalism across the more than seven decades since the end of World War II. Moreover, in a sort of mission creep, opponents of what they decry as a “class-first” position increasingly have come to denounce any expressions of concern for economic inequality as in effect catering to white supremacy. This tendency, which Touré Reed has argued rests on a race-reductionism, has surfaced and spread within the newly revitalized Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), as even many among those who consider themselves socialists object to the organization’s selection of Medicare for All as its key political campaign on the ground that pursuit of decommodified health care for all is objectionable because doing so does not sufficiently center antiracist and anti-disparitarian agendas. I submit that there’s clearly a problem when anti-socialism is defined as socialism. On entering Pierre Huyghe’s exhibition Uumwelt at the Serpentine Gallery, we first notice the large, square, digital screens which flash images in split-second succession. The images are not decipherable, although they seem to reference real things, often organic; one in particular appears to display some kind of cleavage or nudity. They were created in arcane contemporary fashion, with the assistance of researchers into human intelligence based in Japan: a person is presented with pictures and scenarios that he or she is then asked to re-create mentally; this brain activity is scanned, and artificial intelligence, on the basis of these scans, attempts to re-create the things envisaged. These flashing images, accompanied by an unobtrusive electronic soundtrack, also derived from brainwaves, stand out in the scarcely-illuminated gallery space. Soon after, you become aware of the flies: there are hundreds of them, unusually juicy and plump. They settle on the screens, around the light sources, and sometimes on you, the visitor. They form constellations on the ceiling and, in the digital-screen context, seem like demented black pixels.

On entering Pierre Huyghe’s exhibition Uumwelt at the Serpentine Gallery, we first notice the large, square, digital screens which flash images in split-second succession. The images are not decipherable, although they seem to reference real things, often organic; one in particular appears to display some kind of cleavage or nudity. They were created in arcane contemporary fashion, with the assistance of researchers into human intelligence based in Japan: a person is presented with pictures and scenarios that he or she is then asked to re-create mentally; this brain activity is scanned, and artificial intelligence, on the basis of these scans, attempts to re-create the things envisaged. These flashing images, accompanied by an unobtrusive electronic soundtrack, also derived from brainwaves, stand out in the scarcely-illuminated gallery space. Soon after, you become aware of the flies: there are hundreds of them, unusually juicy and plump. They settle on the screens, around the light sources, and sometimes on you, the visitor. They form constellations on the ceiling and, in the digital-screen context, seem like demented black pixels. The world is as close to annihilation as it was last year, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The hands of the organization’s Doomsday Clock will stay at two minutes to midnight, it said, warning that the lack of progress on a host of global threats is a “new abnormal”. Stalled progress on addressing

The world is as close to annihilation as it was last year, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The hands of the organization’s Doomsday Clock will stay at two minutes to midnight, it said, warning that the lack of progress on a host of global threats is a “new abnormal”. Stalled progress on addressing  I’m 47 and my apartment is 325 square feet. Of course, if you measure your life by the size of your apartment you’ve got bigger problems than squeezing between the door and the bed to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Bigger problems than spending too much time playing video games and an inability to love. If you’re going to judge your life by the size of your apartment then you’re better off not thinking of any of it. Just watch some docu-series on Showtime about prison breaks and plug into your twitter feed and let the time pass peacefully. Because the size of your apartment does not matter. Or it does, but it’s not a statement on whether or not you’re successful. But then how do we measure success? Or a better question might be, why?

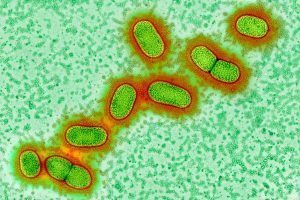

I’m 47 and my apartment is 325 square feet. Of course, if you measure your life by the size of your apartment you’ve got bigger problems than squeezing between the door and the bed to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Bigger problems than spending too much time playing video games and an inability to love. If you’re going to judge your life by the size of your apartment then you’re better off not thinking of any of it. Just watch some docu-series on Showtime about prison breaks and plug into your twitter feed and let the time pass peacefully. Because the size of your apartment does not matter. Or it does, but it’s not a statement on whether or not you’re successful. But then how do we measure success? Or a better question might be, why? If you bled when you brushed your teeth this morning, you might want to get that seen to. We may finally have found the long-elusive cause of Alzheimer’s disease: Porphyromonas gingivalis, the key bacteria in chronic gum disease.

If you bled when you brushed your teeth this morning, you might want to get that seen to. We may finally have found the long-elusive cause of Alzheimer’s disease: Porphyromonas gingivalis, the key bacteria in chronic gum disease. The glass tower that houses George Soros’s office in Manhattan is overflowing with numbers on screens, tracking and predicting the directions of markets around the world. But there’s one that’s particularly hard to figure out — a basic orange chart on a screen analyzing sentiment on social media.

The glass tower that houses George Soros’s office in Manhattan is overflowing with numbers on screens, tracking and predicting the directions of markets around the world. But there’s one that’s particularly hard to figure out — a basic orange chart on a screen analyzing sentiment on social media. N

N

Previously, Van Etten sang of the vagaries of loving too hard, or, worse, of loving the wrong person. “Remind Me Tomorrow” is focussed, lyrically, on how it feels to find peace after a long stretch of ache. It is full of glowing, grounded snapshots, as if Van Etten were trying to pause and capture fulfilled moments so that she might savor them longer. “Malibu,” a road-trip song that takes place on California’s Highway 1, is a slow encomium to a carefree couple steering a “little red number” along the Pacific Coast. Van Etten has written about these sorts of scenarios before—dreamy lost weekends, salty breezes, the world becoming so small and complete that it can only accommodate two people. The difference, this time, is that the fantasy turns real, domestic: “I walked in the door / The Black Crowes playin’ as he cleaned the floor / I thought I couldn’t love him any more.” Van Etten regards her present relationship with the wonderment and gratitude of someone who had perhaps briefly given up on love altogether.

Previously, Van Etten sang of the vagaries of loving too hard, or, worse, of loving the wrong person. “Remind Me Tomorrow” is focussed, lyrically, on how it feels to find peace after a long stretch of ache. It is full of glowing, grounded snapshots, as if Van Etten were trying to pause and capture fulfilled moments so that she might savor them longer. “Malibu,” a road-trip song that takes place on California’s Highway 1, is a slow encomium to a carefree couple steering a “little red number” along the Pacific Coast. Van Etten has written about these sorts of scenarios before—dreamy lost weekends, salty breezes, the world becoming so small and complete that it can only accommodate two people. The difference, this time, is that the fantasy turns real, domestic: “I walked in the door / The Black Crowes playin’ as he cleaned the floor / I thought I couldn’t love him any more.” Van Etten regards her present relationship with the wonderment and gratitude of someone who had perhaps briefly given up on love altogether. Every morning, I buy a black filter coffee from Pret A Manger. There is nothing refined about this. It looks and smells like something you would use to asphalt a road. But the slap of acrid liquid onto tongue is as invigorating as the caffeine itself. Yet though coffee is, ultimately, so much fuel, the means of its production are far from utilitarian: the essence of character and identity are laid bare over the decision to pop a pod in a Nespresso machine (a device whose brilliance lay in convincing Americans that George Clooney was an adequate substitute for sugar and cream) or listen to a Bialetti pot rattle and bubble on the stove top.

Every morning, I buy a black filter coffee from Pret A Manger. There is nothing refined about this. It looks and smells like something you would use to asphalt a road. But the slap of acrid liquid onto tongue is as invigorating as the caffeine itself. Yet though coffee is, ultimately, so much fuel, the means of its production are far from utilitarian: the essence of character and identity are laid bare over the decision to pop a pod in a Nespresso machine (a device whose brilliance lay in convincing Americans that George Clooney was an adequate substitute for sugar and cream) or listen to a Bialetti pot rattle and bubble on the stove top. Curing the childhood eye cancer retinoblastoma often comes at a cost. The tumor, which sprouts in the retina and primarily occurs in children under the age of 5, is fatal if not treated. Yet chemotherapy can cause permanent vision loss, and patients sometimes need surgery to remove one or both eyes. Now, scientists have found that a cancer-slaying virus seems to combat this cancer in mice without serious side effects. A clinical trial has also shown early signs of promise. “It’s potentially a game-changer,” says ophthalmic oncologist David Abramson of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, who wasn’t connected to the study. Researchers have tested cancer-targeting viruses in other types of tumors, but no one had pitted them against retinoblastoma. The tumors grow when there are defects in a molecular pathway that keeps cells from dividing out of control. Oncology researcher Ángel Montero Carcaboso of the Sant Joan de Déu Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, and colleagues used a type of virus known as adenovirus that typically causes only mild respiratory infections in people. It had been genetically modified so it was missing a key gene and could only reproduce inside cells in which the retinoblastoma pathway had malfunctioned.

Curing the childhood eye cancer retinoblastoma often comes at a cost. The tumor, which sprouts in the retina and primarily occurs in children under the age of 5, is fatal if not treated. Yet chemotherapy can cause permanent vision loss, and patients sometimes need surgery to remove one or both eyes. Now, scientists have found that a cancer-slaying virus seems to combat this cancer in mice without serious side effects. A clinical trial has also shown early signs of promise. “It’s potentially a game-changer,” says ophthalmic oncologist David Abramson of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, who wasn’t connected to the study. Researchers have tested cancer-targeting viruses in other types of tumors, but no one had pitted them against retinoblastoma. The tumors grow when there are defects in a molecular pathway that keeps cells from dividing out of control. Oncology researcher Ángel Montero Carcaboso of the Sant Joan de Déu Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, and colleagues used a type of virus known as adenovirus that typically causes only mild respiratory infections in people. It had been genetically modified so it was missing a key gene and could only reproduce inside cells in which the retinoblastoma pathway had malfunctioned. The sixties were a decade of upheaval and progress, and one of the many areas where that revolutionary spirit reared its head was in the art of nonfiction. In previous decades, nonfiction—particularly if written for periodicals—had been seen mostly as ephemeral reportage. It was for catching up on world events, local matters, and human interest, usually read over a morning cup of coffee, stained with those wet, brown rings. Partially because it was churned out on deadline, factual writing was often pooh-poohed as a lesser art form than fictional writing, with the focus merely on the transfer of information, rather than aesthetic splendor, thematic heft, and formal precision.

The sixties were a decade of upheaval and progress, and one of the many areas where that revolutionary spirit reared its head was in the art of nonfiction. In previous decades, nonfiction—particularly if written for periodicals—had been seen mostly as ephemeral reportage. It was for catching up on world events, local matters, and human interest, usually read over a morning cup of coffee, stained with those wet, brown rings. Partially because it was churned out on deadline, factual writing was often pooh-poohed as a lesser art form than fictional writing, with the focus merely on the transfer of information, rather than aesthetic splendor, thematic heft, and formal precision. It’s hardly news that computers are exerting ever more influence over our lives. And we’re beginning to see the first glimmers of some kind of artificial intelligence: computer programs have become much better than humans at well-defined jobs like playing chess and Go, and are increasingly called upon for messier tasks, like driving cars. Once we leave the highly constrained sphere of artificial games and enter the real world of human actions, our artificial intelligences are going to have to make choices about the best course of action in unclear circumstances: they will have to learn to be ethical. I talk to Derek Leben about what this might mean and what kind of ethics our computers should be taught. It’s a wide-ranging discussion involving computer science, philosophy, economics, and game theory.

It’s hardly news that computers are exerting ever more influence over our lives. And we’re beginning to see the first glimmers of some kind of artificial intelligence: computer programs have become much better than humans at well-defined jobs like playing chess and Go, and are increasingly called upon for messier tasks, like driving cars. Once we leave the highly constrained sphere of artificial games and enter the real world of human actions, our artificial intelligences are going to have to make choices about the best course of action in unclear circumstances: they will have to learn to be ethical. I talk to Derek Leben about what this might mean and what kind of ethics our computers should be taught. It’s a wide-ranging discussion involving computer science, philosophy, economics, and game theory. What makes people susceptible to fake news and other forms of strategic misinformation? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

What makes people susceptible to fake news and other forms of strategic misinformation? And what, if anything, can be done about it?