Mallika Rao at The Atlantic:

Jhabvala may have written of Indians, but she wrote largely for the Western Hemisphere. “I have no fans in India,” she told a Los Angeles Times writer in 1993, with what the article described as a “one-note laugh.” A self-confessed “chameleon” at ease in saris or slacks, Jhabvala doled out insights not often shared across racial or class lines. Such a position—an “our woman in India,” to remix the Graham Greene title—would be harder to pull off today, when few audiences are ever exclusive, when everyone seems able to hear everyone else.

Jhabvala may have written of Indians, but she wrote largely for the Western Hemisphere. “I have no fans in India,” she told a Los Angeles Times writer in 1993, with what the article described as a “one-note laugh.” A self-confessed “chameleon” at ease in saris or slacks, Jhabvala doled out insights not often shared across racial or class lines. Such a position—an “our woman in India,” to remix the Graham Greene title—would be harder to pull off today, when few audiences are ever exclusive, when everyone seems able to hear everyone else.

The characters collected in At the End of the Century thus deploy, through Jhabvala’s satirical lens, what could be thought of as endangered speech. “Even physically the English looked cold to her,” goes a line in the story “Miss Sahib,” “with their damp white skins and pale blue eyes.” The England-born teacher who moors the story finds during a stint at home that she longs to return to India, to be once more “surrounded by those glowing coloured skins; and those eyes! The dark, large, liquid Indian eyes! And hair that sprang with such abundance from their heads.”

more here.

The trade in ideas, technologies, art and culture between Africa and her partners flowed both ways, a reality that was accentuated by the slavery trade – something that Green explores in great depth. Not only did African goods and commodities pulse through the arteries of the Atlantic world, cultural knowledge and intellectual capital was taken to the New World in the minds of the millions of human beings who were themselves commodified and exchanged. The Maroons, communities of escaped slaves that emerged in Jamaica, Panama and elsewhere, fought their wars using military theories they had learnt on the continent of their birth. Likewise, the rice plantations of South Carolina were cultivated using not just African labour but also African knowledge. This expertise was intentionally transplanted into American soil by British slave traders who had enslaved thousands of people from the rice-growing regions of Sierra Leone. These Africans were kidnapped to order, their minds as valuable a commodity as their bodies.

The trade in ideas, technologies, art and culture between Africa and her partners flowed both ways, a reality that was accentuated by the slavery trade – something that Green explores in great depth. Not only did African goods and commodities pulse through the arteries of the Atlantic world, cultural knowledge and intellectual capital was taken to the New World in the minds of the millions of human beings who were themselves commodified and exchanged. The Maroons, communities of escaped slaves that emerged in Jamaica, Panama and elsewhere, fought their wars using military theories they had learnt on the continent of their birth. Likewise, the rice plantations of South Carolina were cultivated using not just African labour but also African knowledge. This expertise was intentionally transplanted into American soil by British slave traders who had enslaved thousands of people from the rice-growing regions of Sierra Leone. These Africans were kidnapped to order, their minds as valuable a commodity as their bodies. Edmundson has written an admirably concise yet powerful book. It blends a critical account of Rawls’ work with an original case for democratic socialism hewn from Rawlsian stone. In my opinion, this case has some flaws but it remains a timely contribution to the enduring quest for justice and social stability.

Edmundson has written an admirably concise yet powerful book. It blends a critical account of Rawls’ work with an original case for democratic socialism hewn from Rawlsian stone. In my opinion, this case has some flaws but it remains a timely contribution to the enduring quest for justice and social stability. Take a look at the world poverty clock, which shows in real time the fall in the number of people living in extreme poverty. Or consider two recent bestsellers –

Take a look at the world poverty clock, which shows in real time the fall in the number of people living in extreme poverty. Or consider two recent bestsellers –  ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it.

ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it. Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’

Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’ In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “

In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “ On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published

On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published  “I am not a man, I am dynamite!” Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for this kind of bombast, but most of his works are unassuming in tone, and his sentences are always plain, direct and clear as a bell. Take for instance the celebrated assault on “theorists” in his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872. Theorists, Nietzsche says, know everything there is to know about “world literature”—they can “name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts.” But instead of “plunging into the icy torrent of existence” they merely content themselves with “running nervously up and down the river bank.”

“I am not a man, I am dynamite!” Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for this kind of bombast, but most of his works are unassuming in tone, and his sentences are always plain, direct and clear as a bell. Take for instance the celebrated assault on “theorists” in his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872. Theorists, Nietzsche says, know everything there is to know about “world literature”—they can “name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts.” But instead of “plunging into the icy torrent of existence” they merely content themselves with “running nervously up and down the river bank.” DeVore had hanging in his office an 1838 quote from Darwin’s notebook: “Origin of man now proved … He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” It’s an aphorism that calls to mind one of my favorite characterizations of anthropology—philosophizing with data—and serves as a perfect introduction to the latest work of Richard Wrangham, who has come up with some of the boldest and best new ideas about human evolution.

DeVore had hanging in his office an 1838 quote from Darwin’s notebook: “Origin of man now proved … He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” It’s an aphorism that calls to mind one of my favorite characterizations of anthropology—philosophizing with data—and serves as a perfect introduction to the latest work of Richard Wrangham, who has come up with some of the boldest and best new ideas about human evolution. String theory was originally proposed as a relatively modest attempt to explain some features of strongly-interacting particles, but before too long developed into an ambitious attempt to unite all the forces of nature into a single theory. The great thing about physics is that your theories don’t always go where you want them to, and string theory has had some twists and turns along the way. One major challenge facing the theory is the fact that there are many different ways to connect the deep principles of the theory to the specifics of a four-dimensional world; all of these may actually exist out there in the world, in the form of a cosmological multiverse. Brian Greene is an accomplished string theorist as well as one of the world’s most successful popularizers and advocates for science. We talk about string theory, its cosmological puzzles and promises, and what the future might hold.

String theory was originally proposed as a relatively modest attempt to explain some features of strongly-interacting particles, but before too long developed into an ambitious attempt to unite all the forces of nature into a single theory. The great thing about physics is that your theories don’t always go where you want them to, and string theory has had some twists and turns along the way. One major challenge facing the theory is the fact that there are many different ways to connect the deep principles of the theory to the specifics of a four-dimensional world; all of these may actually exist out there in the world, in the form of a cosmological multiverse. Brian Greene is an accomplished string theorist as well as one of the world’s most successful popularizers and advocates for science. We talk about string theory, its cosmological puzzles and promises, and what the future might hold. NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER

NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER  Neanderthals disappeared from Europe roughly 40,000 years ago, and scientists are still trying to figure out why. Did disease, climate change or competition with modern humans — or maybe a combination of all three — do them in? In a recent

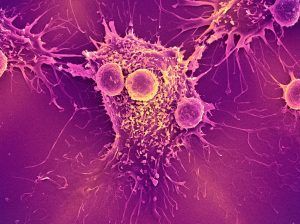

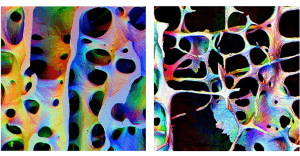

Neanderthals disappeared from Europe roughly 40,000 years ago, and scientists are still trying to figure out why. Did disease, climate change or competition with modern humans — or maybe a combination of all three — do them in? In a recent  Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!” Henry David Thoreau exhorted in his 1854 memoir Walden, in which he extolled the virtues of a “Spartan-like” life. Saint Thomas Aquinas preached that simplicity brings one closer to God. Isaac Newton believed it leads to truth. The process of simplification, we’re told, can illuminate beauty, strip away needless clutter and stress, and help us focus on what really matters. It can also be a sign of aging. Youthful health and vigor depend, in many ways, on complexity. Bones get strength from elaborate scaffolds of connective tissue. Mental acuity arises from interconnected webs of neurons. Even seemingly simple bodily functions like heartbeat rely on interacting networks of metabolic controls, signaling pathways, genetic switches, and circadian rhythms. As our bodies age, these anatomic structures and physiologic processes lose complexity, making them less resilient and ultimately leading to frailty and disease.

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!” Henry David Thoreau exhorted in his 1854 memoir Walden, in which he extolled the virtues of a “Spartan-like” life. Saint Thomas Aquinas preached that simplicity brings one closer to God. Isaac Newton believed it leads to truth. The process of simplification, we’re told, can illuminate beauty, strip away needless clutter and stress, and help us focus on what really matters. It can also be a sign of aging. Youthful health and vigor depend, in many ways, on complexity. Bones get strength from elaborate scaffolds of connective tissue. Mental acuity arises from interconnected webs of neurons. Even seemingly simple bodily functions like heartbeat rely on interacting networks of metabolic controls, signaling pathways, genetic switches, and circadian rhythms. As our bodies age, these anatomic structures and physiologic processes lose complexity, making them less resilient and ultimately leading to frailty and disease. Today, cars with semi-autonomous features are already on the road. Automatic parallel parking has been commercially available since 2003. Cadillac allows drivers to go hands-free on pre-approved routes. Some B.M.W. S.U.V.s can be equipped with, for an additional seventeen-hundred dollars, a system that takes over during “monotonous traffic situations”—more colloquially known as traffic jams. But a mass-produced driverless car remains elusive. In 2013, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published a sliding scale that ranked cars on their level of autonomy. The vast majority of vehicles are still at level zero. A car at level four would be highly autonomous in basic situations, like highways, but would need a human operator. Cars at level five would drive as well as or better than humans, smoothly adapting to rapid changes in their environments, like swerving cars or stray pedestrians. This would require the vehicles to make value judgments, including in versions of a classic philosophy thought experiment called the trolley problem: if a car detects a sudden obstacle—say, a jackknifed truck—should it hit the truck and kill its own driver, or should it swerve onto a crowded sidewalk and kill pedestrians? A human driver might react randomly (if she has time to react at all), but the response of an autonomous vehicle would have to be programmed ahead of time. What should we tell the car to do?

Today, cars with semi-autonomous features are already on the road. Automatic parallel parking has been commercially available since 2003. Cadillac allows drivers to go hands-free on pre-approved routes. Some B.M.W. S.U.V.s can be equipped with, for an additional seventeen-hundred dollars, a system that takes over during “monotonous traffic situations”—more colloquially known as traffic jams. But a mass-produced driverless car remains elusive. In 2013, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published a sliding scale that ranked cars on their level of autonomy. The vast majority of vehicles are still at level zero. A car at level four would be highly autonomous in basic situations, like highways, but would need a human operator. Cars at level five would drive as well as or better than humans, smoothly adapting to rapid changes in their environments, like swerving cars or stray pedestrians. This would require the vehicles to make value judgments, including in versions of a classic philosophy thought experiment called the trolley problem: if a car detects a sudden obstacle—say, a jackknifed truck—should it hit the truck and kill its own driver, or should it swerve onto a crowded sidewalk and kill pedestrians? A human driver might react randomly (if she has time to react at all), but the response of an autonomous vehicle would have to be programmed ahead of time. What should we tell the car to do?