Alex Baia in McSweeney’s:

“Dad, I’m hungry”

“Hi, Hungry. I’m Dad.”

“Why’d you name me ‘Hungry,’ Dad?”

“Because every day you will consume food and entertainment until you are sick, yet every night you will fall asleep empty inside.”

More here.

Alex Baia in McSweeney’s:

“Dad, I’m hungry”

“Hi, Hungry. I’m Dad.”

“Why’d you name me ‘Hungry,’ Dad?”

“Because every day you will consume food and entertainment until you are sick, yet every night you will fall asleep empty inside.”

More here.

Jason Hickel in The Guardian:

Last week, as world leaders and business elites arrived in Davos for the World Economic Forum, Bill Gates tweeted an infographic to his 46 million followers showing that the world has been getting better and better. “This is one of my favourite infographics,” he wrote. “A lot of people underestimate just how much life has improved over the past two centuries.”

Last week, as world leaders and business elites arrived in Davos for the World Economic Forum, Bill Gates tweeted an infographic to his 46 million followers showing that the world has been getting better and better. “This is one of my favourite infographics,” he wrote. “A lot of people underestimate just how much life has improved over the past two centuries.”

Of the six graphs – developed by Max Roser of Our World in Data – the first has attracted the most attention by far. It shows that the proportion of people living in poverty has declined from 94% in 1820 to only 10% today. The claim is simple and compelling. And it’s not just Gates who’s grabbed on to it. These figures have been trotted out in the past year by everyone from Steven Pinker to Nick Kristof and much of the rest of the Davos set to argue that the global extension of free-market capitalism has been great for everyone. Pinker and Gates have gone even further, saying we shouldn’t complain about rising inequality when the very forces that deliver such immense wealth to the richest are also eradicating poverty before our very eyes.

It’s a powerful narrative. And it’s completely wrong.

More here.

by Susan Firer

from Rattle #16, Winter 2001

Sarah Burris in AlterNet:

A new report from the Center for Religion and Civil Culture at the University of Southern California revealed that evangelical Christians can be divided into five different sects. “The Varieties of American Evangelicalism,” detailed the ways in which the community has managed to divide, thanks in part, to President Donald Trump, The Christian Postcited. The five groups are described as Trump-vangelicals, Neo-fundamentalist evangelicals, iVangelicals, Kingdom Christians, and Peace and Justice evangelicals.

A new report from the Center for Religion and Civil Culture at the University of Southern California revealed that evangelical Christians can be divided into five different sects. “The Varieties of American Evangelicalism,” detailed the ways in which the community has managed to divide, thanks in part, to President Donald Trump, The Christian Postcited. The five groups are described as Trump-vangelicals, Neo-fundamentalist evangelicals, iVangelicals, Kingdom Christians, and Peace and Justice evangelicals.

Trump-vangelicals are exactly what many think of when they picture political evangelical Christians. The Post described them as a kind of “Christian nationalist” serving as Trump’s base. They’re primarily white, with only a few Latino or black pastors. “They value access to political power and many believe God chose and blessed Trump in order to ‘make American great again.’”

Neo-fundamentalists can also be folded into the Trump-loving group of evangelicals, the study concluded. The difference is that they still maintain some semblance of their Christian values and distance themselves from the president’s “moral failings.” They focus on understanding their theology and being more personally moral.

iVangelicals sound exactly like the name. The megachurch movement helped spur them on and they aren’t as politically active as the other groups. They tend to be conservative, but they focus more on being non-partisan. Pastors like Joel Osteen and T.D. Jakes are good examples of iVangelicals ministering to mostly white suburbanites.

More here.

From Delanceyplace.com:

In 1966, Robert “Bob” Taylor, an employee at the U.S. government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, had an insight that led to the creation of the internet: “[Bob Taylor’s] most enduring legacy, however, was … a leap of intuition that tied together everything else he had done. This was the ARPANET, the precursor of today’s Internet.

In 1966, Robert “Bob” Taylor, an employee at the U.S. government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, had an insight that led to the creation of the internet: “[Bob Taylor’s] most enduring legacy, however, was … a leap of intuition that tied together everything else he had done. This was the ARPANET, the precursor of today’s Internet.

“Taylor’s original model of a nationwide computer network grew out of his observation that time-sharing was starting to promote the formation of a sort of nationwide computing brotherhood (at this time very few members were women). Whether they were at MIT, Stanford, or UCLA, researchers were all looking for answers to the same general questions. ‘These people began to know one another, share a lot of information, and ask of one another, “How do I use this? Where do I find that?”‘ Taylor recalled. ‘It was really phenomenal to see this computer become a medium that stimulated the formation of a human community.’

“There was still a long way to go before reaching that ideal, however. The community was less like a nation than a swarm of tribal hamlets, often mutually unintelligible or even mutually hostile. Design differences among their machines kept many groups digitally isolated from the others. The risk was that each institution would develop its own unique and insular culture, like related species of birds evolving independently on islands in a vast uncharted sea. Pondering how to bind them into a larger whole, Taylor sought a way for all groups to interact via their computers, each island community enjoying constant access to the others’ machines as though they all lived on one contiguous virtual continent.

More here.

Greg Grandin in The Nation:

Donald Trump has been hot for Venezuela for some time now. In the summer of 2017, Trump, citing George H.W. Bush’s 1989–90 invasion of Panama as a positive precedent, repeatedly pushed his national-security staff to launch a military assault on the crisis-plagued country. Trump was serious. He wanted to know: Why couldn’t the United States just invade? He brought up the idea in meeting after meeting.

Donald Trump has been hot for Venezuela for some time now. In the summer of 2017, Trump, citing George H.W. Bush’s 1989–90 invasion of Panama as a positive precedent, repeatedly pushed his national-security staff to launch a military assault on the crisis-plagued country. Trump was serious. He wanted to know: Why couldn’t the United States just invade? He brought up the idea in meeting after meeting.

His military and civilian advisers, along with foreign leaders, forcefully dismissed the proposal. So, according to NBC, he outsourced Venezuela policy to Florida Senator Marco Rubio, who, along with National Security Adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, began coordinating with the Venezuelan opposition. On Tuesday, Vice President Mike Pence called on Venezuelans to rise up and overthrow the country’s president, Nicolás Maduro. On Wednesday, the head of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, the heretofore unknown 35-year-old Juan Guaidó (whose political godfather is, according to The Washington Post, jailed far-right leader Leopoldo López), declared himself president. Guaidó was quickly recognized by Washington, followed by Canada; a number of powerful Latin American countries, including Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia; and the United Kingdom.

More here.

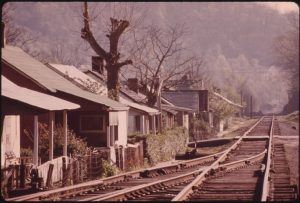

Elizabeth Catte in the Boston Review:

Political veterans such as Pelosi and Israel think that the cornerstones of the emerging left platform—housing as a human right, criminal justice reform, Medicare for all, tuition-free public colleges and trade schools, a federal jobs guarantee, abolition of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and for-profit prisons, campaign finance reform, and a Green New Deal—might perform well in urban centers but not so much elsewhere. Appalachia has become symbolic of the forces that gave us Trump. After all, his pandering to white racial anxiety did find purchase here. His fantasies to make America great again center on our dying coal industry. And the region’s conservative voters, who have been profiled endlessly, have been a reliable stand-in for all Trump voters, absorbing the outrage of progressive readers. But what Pelosi and Israel see as common sense and pragmatism can also be interpreted as tired oversimplifications and a failure of imagination.

Political veterans such as Pelosi and Israel think that the cornerstones of the emerging left platform—housing as a human right, criminal justice reform, Medicare for all, tuition-free public colleges and trade schools, a federal jobs guarantee, abolition of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and for-profit prisons, campaign finance reform, and a Green New Deal—might perform well in urban centers but not so much elsewhere. Appalachia has become symbolic of the forces that gave us Trump. After all, his pandering to white racial anxiety did find purchase here. His fantasies to make America great again center on our dying coal industry. And the region’s conservative voters, who have been profiled endlessly, have been a reliable stand-in for all Trump voters, absorbing the outrage of progressive readers. But what Pelosi and Israel see as common sense and pragmatism can also be interpreted as tired oversimplifications and a failure of imagination.

We remain attached, after all, to narratives that have worked very hard to simplify and neatly divide the state of the union: blue cities, red rural areas, a few swing suburbs. “In a period of political tumult, we grasp for quick certainties,” sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild writes in Strangers in Their Own Land (2016). Indeed, the biggest gift that the left has given the right since 2016 is not a few avowed socialists but the myth that Trump voters are inscrutable and monolithic.

More here.

Maayan Jaffe-Hoffman in the Jerusalem Post:

The potentially game-changing anti-cancer drug is based on SoAP technology, which belongs to the phage display group of technologies. It involves the introduction of DNA coding for a protein, such as an antibody, into a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria. That protein is then displayed on the surface of the phage. Researchers can use these protein-displaying phages to screen for interactions with other proteins, DNA sequences and small molecules.

The potentially game-changing anti-cancer drug is based on SoAP technology, which belongs to the phage display group of technologies. It involves the introduction of DNA coding for a protein, such as an antibody, into a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria. That protein is then displayed on the surface of the phage. Researchers can use these protein-displaying phages to screen for interactions with other proteins, DNA sequences and small molecules.

In 2018, a team of scientists won the Nobel Prize for their work on phage display in the directed evolution of new proteins – in particular, for the production of antibody therapeutics.

AEBi is doing something similar but with peptides, compounds of two or more amino acids linked in a chain. According to Morad, peptides have several advantages over antibodies, including that they are smaller, cheaper, and easier to produce and regulate.

More here.

Scott Atran in Scientific American:

With support from Minerva Research Initiative of the U.S. Department of Defense and National Science Foundation, we recently published the first neuroimaging study of a radicalizing population. The research used ethnographic surveys and psychological analysis to identify 535 young Muslim men in and around Barcelona—where ISIS-supporting jihadis killed 13 people and wounded 100 more in the city center in August 2017.

With support from Minerva Research Initiative of the U.S. Department of Defense and National Science Foundation, we recently published the first neuroimaging study of a radicalizing population. The research used ethnographic surveys and psychological analysis to identify 535 young Muslim men in and around Barcelona—where ISIS-supporting jihadis killed 13 people and wounded 100 more in the city center in August 2017.

Half of these young men (267) scored higher that the other half (268) on all measures of vulnerability to recruitment into violent extremism. From the more vulnerable group, 38 men, second-generation immigrants of Moroccan origin who had already “expressed a willingness to engage in or facilitate violence associated with jihadist causes,” agreed to have their brains scanned.

The young men selected for the neuroimaging study then played a ball-throwing game (Cyberball) with fellow Spaniards, and half of them were abruptly and deliberately excluded from being passed the ball. Their brains were then scanned while asking them questions about behavior and policies they considered sacred and inviolable (e.g., forbidding cartoons of the Prophet, preventing gay marriage) as well non-sacred but important values (e.g., women wearing the veil, unrestricted construction of mosques).

More here.

Nick Barrowman at The New Atlantis:

The word data is derived from the Latin meaning “given.” Rob Kitchin, a social scientist in Ireland and the author of The Data Revolution (2014), has argued that instead of considering data as given it would be more appropriate to think of it as taken, for which the Latin would be capta. Except in divine revelation, data is never simply given, nor should it be accepted on faith. How data are construed, recorded, and collected is the result of human decisions — decisions about what exactly to measure, when and where to do so, and by what methods. Inevitably, what gets measured and recorded has an impact on the conclusions that are drawn.

For example, rates of domestic violence were historically underestimated because these crimes were rarely documented. Polling data may miss people who are homeless or institutionalized, and if marginalized people are incompletely represented by opinion polls, the results may be skewed. Data sets often preferentially include people who are more easily reached or more likely to respond.

more here.

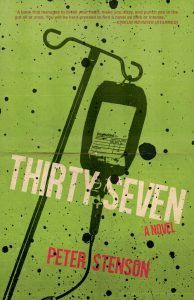

Katherine Coldiron at 3:AM Magazine:

How do you recommend an experience you never want to have again? How does a film critic say, for instance, that Requiem for a Dream is a must-watch, when it’s infused with such ugliness and despair? When a piece of art is unapologetically dark and unpleasant but of objectively excellent quality, finding a way to push audiences toward it is a challenge.

How do you recommend an experience you never want to have again? How does a film critic say, for instance, that Requiem for a Dream is a must-watch, when it’s infused with such ugliness and despair? When a piece of art is unapologetically dark and unpleasant but of objectively excellent quality, finding a way to push audiences toward it is a challenge.

In this vein is Thirty-Seven, by American novelist Peter Stenson, an intense, exceptionally well-made, unforgettable book. I loved every word, but I can’t suggest it’s an enjoyable read. It’s a horror story without ghosts or beasts, a book that continually evokes Rorschach, in Watchmen, saying “as dark as it gets.” Meticulously constructed, Hitchcockian in its layering of tension, Faulknerian in its network of ideas, wise and strange as an angel, black as a night in a dungeon. Certainly one of the best books I read in 2018. But difficult to recommend. At least, not if you’re looking for a comfortable ride.

more here.

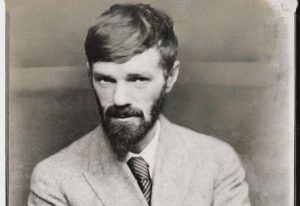

Geoff Dyer at the New Statesman:

The best parts of “Art and Morality” (1925) are not about art or morality but – via an extraordinary speculative detour into the lives of ancient Egyptians – about how the “Kodak” habit of photographing oneself all the time has fundamentally changed our sense of ourselves: a prophetic diagnosis of a defining malaise of the iPhone era. In an editorial note to “Introduction to Pictures” the scholar James T Boulton rightly points out that the essay “does not once refer to pictures”. This tendency to stray from stated intentions was best expressed by Lawrence himself on 5 September 1914. “Out of sheer rage I’ve begun my book about Thomas Hardy. It will be about anything but Thomas Hardy I am afraid – queer stuff – but not bad.”

The best parts of “Art and Morality” (1925) are not about art or morality but – via an extraordinary speculative detour into the lives of ancient Egyptians – about how the “Kodak” habit of photographing oneself all the time has fundamentally changed our sense of ourselves: a prophetic diagnosis of a defining malaise of the iPhone era. In an editorial note to “Introduction to Pictures” the scholar James T Boulton rightly points out that the essay “does not once refer to pictures”. This tendency to stray from stated intentions was best expressed by Lawrence himself on 5 September 1914. “Out of sheer rage I’ve begun my book about Thomas Hardy. It will be about anything but Thomas Hardy I am afraid – queer stuff – but not bad.”

Intended as part of a series called “Writers of the Day”, the manuscript, which had veered far from any template, was not accepted for publication. Lawrence wanted it to leave the original brief still further behind and began recasting something that had been “mostly philosophicalish, slightly about Hardy” into a more explicit statement of his “‘philosophy’ (forgive the word)”.

more here.

Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad in Atlantis:

The history of Islam’s relation to science has largely been one of harmony. It offers no real parallel to the occasional bouts of suspicion toward science that the Christian world experienced. Today, many Muslims can be found in the fields of medicine and engineering. Even the ultraconservative Muslims who long for a return to the ethical norms of the seventh century see no need to abandon cell phones to do so, and even the most extreme of Islamic extremists envies the high-tech oil-extraction techniques and the weaponry of the West. Muslims, both conservative and liberal, issue fatwas (legal opinions) over the Internet without any hesitation over the technology they employ and with no fear that it may be haram (prohibited).

The history of Islam’s relation to science has largely been one of harmony. It offers no real parallel to the occasional bouts of suspicion toward science that the Christian world experienced. Today, many Muslims can be found in the fields of medicine and engineering. Even the ultraconservative Muslims who long for a return to the ethical norms of the seventh century see no need to abandon cell phones to do so, and even the most extreme of Islamic extremists envies the high-tech oil-extraction techniques and the weaponry of the West. Muslims, both conservative and liberal, issue fatwas (legal opinions) over the Internet without any hesitation over the technology they employ and with no fear that it may be haram (prohibited).

However, although contemporary Muslims tend not to be averse to science or technology, their strong belief in the compatibility of science and Islam may leave them vulnerable to dubious efforts to equate the two. The effort to harmonize modern technical knowledge and practice with Islamic teaching is part of a project known as the “Islamization of knowledge,” and is quite popular among Muslim intellectuals today. The most visible area of this intellectual work has been in the world of finance, with the development of so-called “Islamic banking.” A wide variety of venture-capital investments, joint-development projects, and partnership financing have been devised to avoid the appearance of charging interest, a practice forbidden by traditional Muslim jurisprudence. On a smaller scale, there has been a rising interest in bringing the sciences into a conversation with Islamic teachings.

An offshoot of this project takes an absurd turn: it attempts to demonstrate, in effect, that the Koran is a scientific textbook — that it is not merely compatible with science but actually foretells and validates specific modern scientific theories. This movement is troubling in part because it is becoming associated with the term “Islamic science,” which has long been used to refer to the medieval Golden Age during which the Muslim world made important contributions to natural philosophy, medicine, and mathematics. Confusing this new movement with that important period is a disservice to history. Moreover, this new movement to seek out science in the Koran is contrary to the scientific method and, in ignoring the Koran’s warning against confusing allegory with basic facts (3:7), is contrary to Islamic teaching.

More here.

Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

In 2014 John Cryan, a professor at University College Cork in Ireland, attended a meeting in California about Alzheimer’s disease. He wasn’t an expert on dementia. Instead, he studied the microbiome, the trillions of microbes inside the healthy human body. Dr. Cryan and other scientists were beginning to find hints that these microbes could influence the brain and behavior. Perhaps, he told the scientific gathering, the microbiome has a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The idea was not well received. “I’ve never given a talk to so many people who didn’t believe what I was saying,” Dr. Cryan recalled. A lot has changed since then: Research continues to turn up remarkable links between the microbiome and the brain. Scientists are finding evidence that microbiome may play a role not just in Alzheimer’s disease, but Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, autism and other conditions.

In 2014 John Cryan, a professor at University College Cork in Ireland, attended a meeting in California about Alzheimer’s disease. He wasn’t an expert on dementia. Instead, he studied the microbiome, the trillions of microbes inside the healthy human body. Dr. Cryan and other scientists were beginning to find hints that these microbes could influence the brain and behavior. Perhaps, he told the scientific gathering, the microbiome has a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The idea was not well received. “I’ve never given a talk to so many people who didn’t believe what I was saying,” Dr. Cryan recalled. A lot has changed since then: Research continues to turn up remarkable links between the microbiome and the brain. Scientists are finding evidence that microbiome may play a role not just in Alzheimer’s disease, but Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, autism and other conditions.

For some neuroscientists, new studies have changed the way they think about the brain. One of the skeptics at that Alzheimer’s meeting was Sangram Sisodia, a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago. He wasn’t swayed by Dr. Cryan’s talk, but later he decided to put the idea to a simple test. “It was just on a lark,” said Dr. Sisodia. “We had no idea how it would turn out.” He and his colleagues gave antibiotics to mice prone to develop a version of Alzheimer’s disease, in order to kill off much of the gut bacteria in the mice. Later, when the scientists inspected the animals’ brains, they found far fewer of the protein clumps linked to dementia.

Just a little disruption of the microbiome was enough to produce this effect. Young mice given antibiotics for a week had fewer clumps in their brains when they grew old, too.

More here.

Matt Davis in Big Think:

Lab-grown beef may very well be the path forward. In 2008, it was estimated that just half a pound of lab-grown beef would cost $1 million. Then, on August 5, 2013, the first lab-grown hamburger was eaten. It cost $325,000 and took two years to make. Just two years later, the same amount of lab-grown beef costs about $11 to make.

Lab-grown beef may very well be the path forward. In 2008, it was estimated that just half a pound of lab-grown beef would cost $1 million. Then, on August 5, 2013, the first lab-grown hamburger was eaten. It cost $325,000 and took two years to make. Just two years later, the same amount of lab-grown beef costs about $11 to make.

Lab-grown beef checks almost all of the boxes: it doesn’t require animal cruelty, and a study in Environmental Science and Technology showed that it could cut emissions from conventionally produced meat by up to 96 percent and cut down on the land use required for meat production by 99 percent. In the U.S., where cow pastures take up 35 percent of available land — that’s about 654 million acres — this could be huge. Imagine having 647 million acres for development, housing, national parks, anything at all!

But does lab-grown beef pass the most crucial test? Does it taste like an honest-to-goodness hamburger?

More here.

Henry Farrell in Crooked Timber:

Attention conservation notice: long (nearly 5,000 words long) essay on the economic power of ideas. To its credit, the questions discussed are plausibly important. To its detriment, the arguments are less arguments than gestures, and the structure is decidedly baggy.

For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been wanting to write a response to Aaron Major’s (paywalled) article on ideas and economic power for Catalyst. Now there’s a second piece by Jeremy Adelman in Aeon on Thomas Piketty and Adam Tooze. I think they’re both wrong, but in different ways. Major’s piece suggests that economic ideas don’t really matter very much – it’s the economic base, not the superstructure that’s doing the work. Adelman, in contrast, think that ideas are super important – he just thinks that Piketty and Tooze have ones that are leading us in the wrong direction.

These arguments come from radically different places, but they have one thing in common. They both substantially underestimate the role that ideas have played in getting us to where we are on the left, and what they they’re likely to do for us in the near future.

More here.

Dani Rodrik in Project Syndicate:

The main political beneficiaries of the social and economic fractures wrought by globalization and technological change, it is fair to say, have so far been right-wing populists. Politicians like Donald Trump in the United States, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have ridden to power by capitalizing on the growing animus against established political elites and exploiting latent nativist sentiment.

The main political beneficiaries of the social and economic fractures wrought by globalization and technological change, it is fair to say, have so far been right-wing populists. Politicians like Donald Trump in the United States, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have ridden to power by capitalizing on the growing animus against established political elites and exploiting latent nativist sentiment.

The left and progressive groups have been largely missing in action. The left’s relative weakness partly reflects the decline of unions and organized labor groups, which have historically formed the backbone of leftist and socialist movements. But ideological abdication has also played an important role. As parties of the left became more dependent on educated elites instead of the working class, their policy ideas aligned more closely with financial and corporate interests.

The remedies on offer from mainstream leftist parties remained correspondingly limited: more spending on education, improved social-welfare policies, a bit more progressivity in taxation, and little else. The left’s program was more about sugarcoating the prevailing system than addressing the fundamental sources of economic, social, and political inequities.

More here.

Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker:

For around a decade, people who think critically about the media have worried about filter bubbles—algorithmic or social structures of information flow that help us see only the news that we want to see. Filter bubbles make it easy to ignore information that could change our views. But the Covington story is an example of a different problem. It’s a story that’s disproportionately talked about and hard to avoid. It’s relatively inconsequential, but also inescapable. There is no bubble strong enough to keep it out.

For around a decade, people who think critically about the media have worried about filter bubbles—algorithmic or social structures of information flow that help us see only the news that we want to see. Filter bubbles make it easy to ignore information that could change our views. But the Covington story is an example of a different problem. It’s a story that’s disproportionately talked about and hard to avoid. It’s relatively inconsequential, but also inescapable. There is no bubble strong enough to keep it out.

The Covington saga isn’t fake news, strictly speaking. The events on the Mall really happened; what’s more, the surrounding story raises many questions of broad, genuine interest. How much should we hold teen-agers accountable for their political views? Would a group of nonwhite demonstrators have been permitted to behave as the Covington boys did? What is the moral status of Catholicism, and of socially conservative religious institutions generally? (What if the boys had been students at a Jewish or Muslim school?) How reactive should journalists be? These subjects are interesting to debate, as are the reputations of Sandmann and Phillips. All of this lends the Covington video a kind of moral momentum. As more people weigh in, the momentum builds.

It would be wrong, however, to take the moral interest of the Covington video at face value.

More here. [Thanks to Dan Dennett.]