Theodore Dalrymple in Standpoint:

Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief.

Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief.

But quite apart from the valuable function that the bad performs in helping us to appreciate the good, I would amend Connolly’s dictum as follows: the more books we read, the clearer it becomes that there is no book, however bad or merely mediocre it may be, that has nothing to say to us, for every book tells us something. Thus reading a book may be a relative waste of time, for we might be doing something better or more useful than reading it, such as reading a better book. But it is never a waste of time in the absolute sense, at least for the inquisitive or reflective mind. For the uninquisitve or unreflective mind, of course, Armageddon itself would be dull and without interest or lessons.

Every contact leaves a trace, said the great French forensic scientist, Edmond Locard; and likewise, every book tells us something (even if, unlike every crime, it appears to leave no trace). This is especially so for those, which is almost all of us, who have access to the internet.

More here.

OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS—

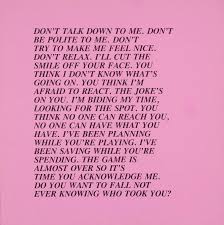

OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS— If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The

If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The  When

When  Soraya Roberts in Longreads:

Soraya Roberts in Longreads: First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently.

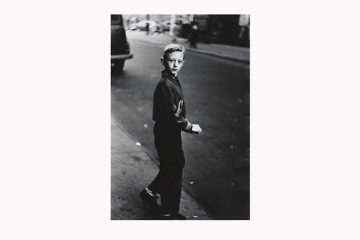

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently. In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of

In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of  I

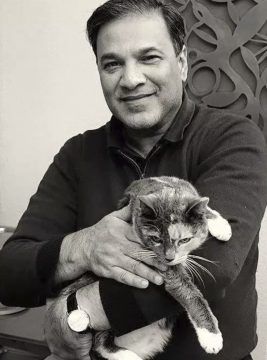

I In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

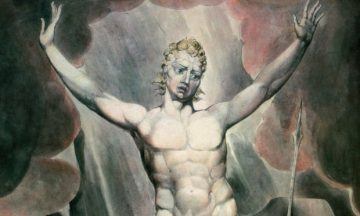

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books: The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this?

The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this? IN 1997

IN 1997 He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”

He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”