Meehan Crist at the LRB:

There is a belief, particularly prevalent among scientists, that science writing is more or less glorified PR – scientists do the intellectual work of discovery and writers port their findings from lab to public – but Silent Spring is a powerful reminder that great science writing can expand our scientific and cultural imaginations. Rarely has the work of a single author – or, indeed, a single book – had such an immediate and profound impact on society. Silent Spring was the first book to persuade a wide audience of the interconnectedness of all life, ushering in the idea that ‘nature’ refers to ecosystems that include humans. It spurred the passage in the United States of the Clean Air Act (1963), the Wilderness Act (1964), the National Environmental Policy Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Endangered Species Act (1973). Perhaps most significant, it showed how human health and well-being ties in with the health of our environment, leading to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. No wonder, then, that writers, activists and scientists concerned about the ongoing destruction of biodiversity and the catastrophic effects of climate change look to Carson with urgent nostalgia.

There is a belief, particularly prevalent among scientists, that science writing is more or less glorified PR – scientists do the intellectual work of discovery and writers port their findings from lab to public – but Silent Spring is a powerful reminder that great science writing can expand our scientific and cultural imaginations. Rarely has the work of a single author – or, indeed, a single book – had such an immediate and profound impact on society. Silent Spring was the first book to persuade a wide audience of the interconnectedness of all life, ushering in the idea that ‘nature’ refers to ecosystems that include humans. It spurred the passage in the United States of the Clean Air Act (1963), the Wilderness Act (1964), the National Environmental Policy Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Endangered Species Act (1973). Perhaps most significant, it showed how human health and well-being ties in with the health of our environment, leading to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. No wonder, then, that writers, activists and scientists concerned about the ongoing destruction of biodiversity and the catastrophic effects of climate change look to Carson with urgent nostalgia.

more here.

Truly, the older I get, the older are the books I want to read, and the fewer. I creep further and further back into history. I hide in the murk of lost time.

Truly, the older I get, the older are the books I want to read, and the fewer. I creep further and further back into history. I hide in the murk of lost time. TWO YEARS AGO

TWO YEARS AGO Instagram launched in 2010, some hundred and twenty years after Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The slender novel is a fable of a new Narcissus, of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages and conforms to the life he has lived while his body does not. Dorian Gray, awakened to the magnificence and fleetingness of his own youth by an aesthete’s words and the glory of his picture, breathes a murmured prayer that his soul might be exchanged for a visage and body never older than that singular summer day they were portrayed. By an unknown magic his prayer is answered, and the accidents of his flesh are somehow severed from his essence so that he may live as he likes, physically untouched and unchanged. But this division of body and soul leads Dorian to ethical dissolution. For by the fixed innocence of his appearance, the link between action and consequence is severed.

Instagram launched in 2010, some hundred and twenty years after Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The slender novel is a fable of a new Narcissus, of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages and conforms to the life he has lived while his body does not. Dorian Gray, awakened to the magnificence and fleetingness of his own youth by an aesthete’s words and the glory of his picture, breathes a murmured prayer that his soul might be exchanged for a visage and body never older than that singular summer day they were portrayed. By an unknown magic his prayer is answered, and the accidents of his flesh are somehow severed from his essence so that he may live as he likes, physically untouched and unchanged. But this division of body and soul leads Dorian to ethical dissolution. For by the fixed innocence of his appearance, the link between action and consequence is severed. The Spercheios river—which, legend tells us, was dear to the warrior Achilles—marks the southern boundary of the great Thessalian plain in central Greece. I arrived there in late October, but it still felt like summer, and few people were around. Away on the left, the foothills of Mount Oiti were hazed with heat. On my right, at some distance from the road, screened by cotton fields and intermittent olive groves, flowed the Spercheios. At the village of Paliourio, road and river converged, and leaving my car, I wandered down a track that led to a shattered bridge shored with makeshift planking. The river itself was sparkling, picturesquely overhung with oak and wild olive, but on closer inspection I saw machinery and discarded appliances rusting in its shallows.

The Spercheios river—which, legend tells us, was dear to the warrior Achilles—marks the southern boundary of the great Thessalian plain in central Greece. I arrived there in late October, but it still felt like summer, and few people were around. Away on the left, the foothills of Mount Oiti were hazed with heat. On my right, at some distance from the road, screened by cotton fields and intermittent olive groves, flowed the Spercheios. At the village of Paliourio, road and river converged, and leaving my car, I wandered down a track that led to a shattered bridge shored with makeshift planking. The river itself was sparkling, picturesquely overhung with oak and wild olive, but on closer inspection I saw machinery and discarded appliances rusting in its shallows. In 1996,

In 1996,  The

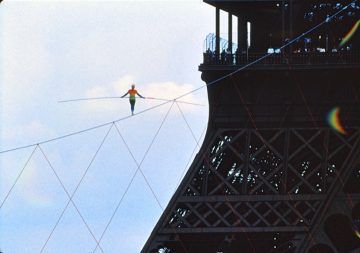

The Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing.

Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing. Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world.

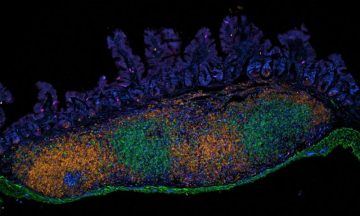

Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world. Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human

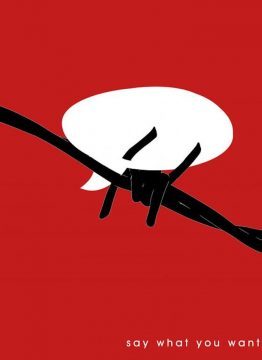

Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human  ‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

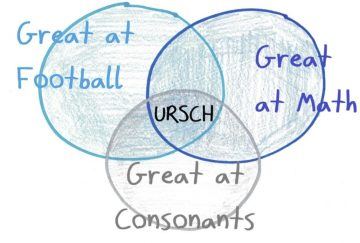

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision? Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive.

Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive. There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of  Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city. S

S