Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

Israeli physicists think they have confirmed one of the late Stephen Hawking’s most famous predictions by creating the sonic equivalent of a black hole out of an exotic superfluid of ultra-cold atoms. Jeff Steinhauer and colleagues at the Israel Institute of Technology (Technion) described these intriguing experimental results in a new paper in Nature.

Israeli physicists think they have confirmed one of the late Stephen Hawking’s most famous predictions by creating the sonic equivalent of a black hole out of an exotic superfluid of ultra-cold atoms. Jeff Steinhauer and colleagues at the Israel Institute of Technology (Technion) described these intriguing experimental results in a new paper in Nature.

The standard description of a black hole is an object with such a strong gravitational force that light can’t even escape once it moves behind a point of no return known as the event horizon. But in the 1970s, Hawking demonstrated that—theoretically, at least—black holes should emit tiny amounts of radiation and gradually evaporate over time.

Blame the intricacies of quantum mechanics for this Hawking radiation. From a quantum perspective, the vacuum of space continually produces pairs of virtual particles (matter and antimatter) that pop into existence and just as quickly annihilate away. Hawking proposed that a virtual particle pair, if it popped up at the event horizon of a black hole, might have different fates: one might fall in, but the other could escape, making it seem as if the black hole were emitting radiation. The black hole would lose a bit of its mass in the process. The bigger the black hole, the longer it takes to evaporate. (Mini-black holes the size of a subatomic particle would wink out of existence almost instantaneously.)

More here.

The debate over meritocracy has been intensifying. Is it a good thing? A bad thing? Do we want it or don’t we?

The debate over meritocracy has been intensifying. Is it a good thing? A bad thing? Do we want it or don’t we? Editors’ note: This is the third installment in a new series, “Op-Eds From the Future,” in which science fiction authors, futurists, philosophers and scientists write Op-Eds that they imagine we might read 10, 20 or even 100 years from now. The challenges they predict are imaginary — for now — but their arguments illuminate the urgent questions of today and prepare us for tomorrow. The opinion piece below is a work of fiction.

Editors’ note: This is the third installment in a new series, “Op-Eds From the Future,” in which science fiction authors, futurists, philosophers and scientists write Op-Eds that they imagine we might read 10, 20 or even 100 years from now. The challenges they predict are imaginary — for now — but their arguments illuminate the urgent questions of today and prepare us for tomorrow. The opinion piece below is a work of fiction. It’s a source of great irony and outrage that the Turkish authorities have decided to investigate

It’s a source of great irony and outrage that the Turkish authorities have decided to investigate  About a year ago, some—but not all—of the mice in

About a year ago, some—but not all—of the mice in  Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver seems at least in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver seems at least in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “ It’s fun to spend time thinking about how other people should behave, but fortunately we also have an inner voice that keeps offering opinions about how we should behave ourselves: our conscience. Where did that come from? Today’s guest, Patricia Churchland, is a philosopher and neuroscientist, one of the founders of the subfield of “neurophilosophy.” We dig into the neuroscience of it all, especially how neurochemicals like

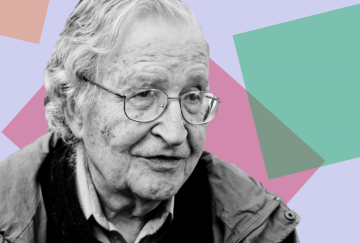

It’s fun to spend time thinking about how other people should behave, but fortunately we also have an inner voice that keeps offering opinions about how we should behave ourselves: our conscience. Where did that come from? Today’s guest, Patricia Churchland, is a philosopher and neuroscientist, one of the founders of the subfield of “neurophilosophy.” We dig into the neuroscience of it all, especially how neurochemicals like  Noam Chomsky: There have been changes, even before the recent shift you mention. Both parties shifted to the right during the neoliberal years: the mainstream Democrats became something like the former moderate Republicans, and the Republicans drifted virtually off the spectrum. There’s merit, I think, in the observation by Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein that increasingly since the Newt Gingrich years—and strikingly in Mitch McConnell’s Senate—the Republican Party has become a “radical insurgency” that is largely abandoning normal parliamentary politics. That shift—which predates Donald Trump—has created a substantial gap between the two parties. In the media it’s often called “polarization,” but that’s hardly an accurate description.

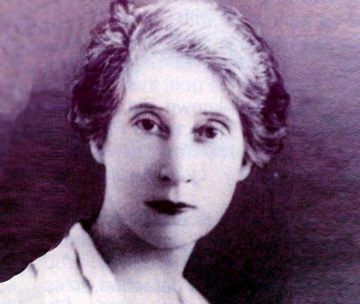

Noam Chomsky: There have been changes, even before the recent shift you mention. Both parties shifted to the right during the neoliberal years: the mainstream Democrats became something like the former moderate Republicans, and the Republicans drifted virtually off the spectrum. There’s merit, I think, in the observation by Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein that increasingly since the Newt Gingrich years—and strikingly in Mitch McConnell’s Senate—the Republican Party has become a “radical insurgency” that is largely abandoning normal parliamentary politics. That shift—which predates Donald Trump—has created a substantial gap between the two parties. In the media it’s often called “polarization,” but that’s hardly an accurate description. The life and career of the gifted Glaswegian writer Catherine Carswell was marked by such alarming and recurrent notoriety that her present obscurity is baffling. In 1908, still in her twenties and working as a newspaper critic, Carswell made headlines when a judge ruled that her husband, who suffered from murderous paranoid delusions, was of unsound mind at the time of their wedding. Although the couple had a daughter, Carswell got the marriage annulment she’d fought for and an enduring legal precedent was set. In 1930, she became a pariah in Scotland thanks to her sexually frank biography of national poet-hero Robert Burns, which offended zealous keepers of the Burns myth. One reader saw fit to send the author a letter containing a bullet, with the suggestion that she “leave the world a better, brighter, cleaner place.” Then, in 1932, Carswell’s biography of her friend D.H. Lawrence, The Savage Pilgrimage, was sensationally withdrawn from stores amid accusations of libel—not from the subject, who died in 1930, but from John Middleton Murry, the writer and critic. Murry, Lawrence’s posthumous biographer and the widower of Katherine Mansfield, had a tangled and volatile history with the late novelist and his wife, Frieda. An angry Lawrence once told Murry he was “an obscene bug sucking my life away.”

The life and career of the gifted Glaswegian writer Catherine Carswell was marked by such alarming and recurrent notoriety that her present obscurity is baffling. In 1908, still in her twenties and working as a newspaper critic, Carswell made headlines when a judge ruled that her husband, who suffered from murderous paranoid delusions, was of unsound mind at the time of their wedding. Although the couple had a daughter, Carswell got the marriage annulment she’d fought for and an enduring legal precedent was set. In 1930, she became a pariah in Scotland thanks to her sexually frank biography of national poet-hero Robert Burns, which offended zealous keepers of the Burns myth. One reader saw fit to send the author a letter containing a bullet, with the suggestion that she “leave the world a better, brighter, cleaner place.” Then, in 1932, Carswell’s biography of her friend D.H. Lawrence, The Savage Pilgrimage, was sensationally withdrawn from stores amid accusations of libel—not from the subject, who died in 1930, but from John Middleton Murry, the writer and critic. Murry, Lawrence’s posthumous biographer and the widower of Katherine Mansfield, had a tangled and volatile history with the late novelist and his wife, Frieda. An angry Lawrence once told Murry he was “an obscene bug sucking my life away.” “To read a text isn’t to discover new facts about it,” says Moi, “it is to figure out what it has to say to us.”

“To read a text isn’t to discover new facts about it,” says Moi, “it is to figure out what it has to say to us.” The truth, as strongly suggested in Eugene Onegin, is that Pushkin’s attitudes towards the country were as conflicted as the twin self the novel in verse projects. When he stayed at Mikhailovskoye after graduating from his elite Petersburg lycée he was both delighted and impatient. ‘I remember how happy I was with village life, Russian baths, strawberries and so on,’ he wrote. ‘But all this did not please me for long.’ In the country he was constantly riding out to find companionship, love and sex among his gentry neighbours – failing that, to have sex with one of the family serfs – but still had time enough for composition. In one three-month autumn stay in Boldino, where he was less desperate for company – just engaged, but without his future wife, Natalya Goncharova – he wrote thirty poems, all five Tales of Belkin and the satirical History of the Village of Goryukhino. He also wrote the ending of Eugene Onegin and four short plays, including Mozart and Salieri, the work by which he is – invisibly – best known to modern popular culture outside Russia, via the Peter Shaffer play it inspired, Amadeus, rendered onto the big screen by Miloš Forman.

The truth, as strongly suggested in Eugene Onegin, is that Pushkin’s attitudes towards the country were as conflicted as the twin self the novel in verse projects. When he stayed at Mikhailovskoye after graduating from his elite Petersburg lycée he was both delighted and impatient. ‘I remember how happy I was with village life, Russian baths, strawberries and so on,’ he wrote. ‘But all this did not please me for long.’ In the country he was constantly riding out to find companionship, love and sex among his gentry neighbours – failing that, to have sex with one of the family serfs – but still had time enough for composition. In one three-month autumn stay in Boldino, where he was less desperate for company – just engaged, but without his future wife, Natalya Goncharova – he wrote thirty poems, all five Tales of Belkin and the satirical History of the Village of Goryukhino. He also wrote the ending of Eugene Onegin and four short plays, including Mozart and Salieri, the work by which he is – invisibly – best known to modern popular culture outside Russia, via the Peter Shaffer play it inspired, Amadeus, rendered onto the big screen by Miloš Forman. No novel of the past century

No novel of the past century The average person eats at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and breathes in a similar quantity, according to the first study to estimate human ingestion of plastic pollution. The true number is likely to be many times higher, as only a small number of foods and drinks have been analysed for plastic contamination. The scientists reported that drinking a lot of bottled water drastically increased the particles consumed. The health impacts of ingesting microplastic are unknown, but they could release toxic substances. Some pieces are small enough to penetrate human tissues, where they could trigger immune reactions.

The average person eats at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and breathes in a similar quantity, according to the first study to estimate human ingestion of plastic pollution. The true number is likely to be many times higher, as only a small number of foods and drinks have been analysed for plastic contamination. The scientists reported that drinking a lot of bottled water drastically increased the particles consumed. The health impacts of ingesting microplastic are unknown, but they could release toxic substances. Some pieces are small enough to penetrate human tissues, where they could trigger immune reactions. The big question that I keep asking myself at the moment is whether it’s possible that predictive processing, the vision of the predictive mind I’ve been working on lately, is as good as it seems to be. It keeps me awake a little bit at night wondering whether anything could touch so many bases as this story seems to. It looks to me as if it provides a way of moving towards a third generation of artificial intelligence. I’ll come back to that in a minute. It also looks to me as if it shows how the stuff that I’ve been interested in for so long, in terms of the extended mind and embodied cognition, can be both true and scientifically tractable, and how we can get something like a quantifiable grip on how neural processing weaves together with bodily processing weaves together with actions out there in the world. It also looks as if this might give us a grip on the nature of conscious experience. And if any theory were able to do all of those things, it would certainly be worth taking seriously. I lie awake wondering whether any theory could be so good as to be doing all these things at once, but that’s what we’ll be talking about.

The big question that I keep asking myself at the moment is whether it’s possible that predictive processing, the vision of the predictive mind I’ve been working on lately, is as good as it seems to be. It keeps me awake a little bit at night wondering whether anything could touch so many bases as this story seems to. It looks to me as if it provides a way of moving towards a third generation of artificial intelligence. I’ll come back to that in a minute. It also looks to me as if it shows how the stuff that I’ve been interested in for so long, in terms of the extended mind and embodied cognition, can be both true and scientifically tractable, and how we can get something like a quantifiable grip on how neural processing weaves together with bodily processing weaves together with actions out there in the world. It also looks as if this might give us a grip on the nature of conscious experience. And if any theory were able to do all of those things, it would certainly be worth taking seriously. I lie awake wondering whether any theory could be so good as to be doing all these things at once, but that’s what we’ll be talking about. The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire.

The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire. The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how

The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how