Micah Meadowcroft in The New Atlantis:

Instagram launched in 2010, some hundred and twenty years after Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The slender novel is a fable of a new Narcissus, of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages and conforms to the life he has lived while his body does not. Dorian Gray, awakened to the magnificence and fleetingness of his own youth by an aesthete’s words and the glory of his picture, breathes a murmured prayer that his soul might be exchanged for a visage and body never older than that singular summer day they were portrayed. By an unknown magic his prayer is answered, and the accidents of his flesh are somehow severed from his essence so that he may live as he likes, physically untouched and unchanged. But this division of body and soul leads Dorian to ethical dissolution. For by the fixed innocence of his appearance, the link between action and consequence is severed.

Instagram launched in 2010, some hundred and twenty years after Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The slender novel is a fable of a new Narcissus, of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages and conforms to the life he has lived while his body does not. Dorian Gray, awakened to the magnificence and fleetingness of his own youth by an aesthete’s words and the glory of his picture, breathes a murmured prayer that his soul might be exchanged for a visage and body never older than that singular summer day they were portrayed. By an unknown magic his prayer is answered, and the accidents of his flesh are somehow severed from his essence so that he may live as he likes, physically untouched and unchanged. But this division of body and soul leads Dorian to ethical dissolution. For by the fixed innocence of his appearance, the link between action and consequence is severed.

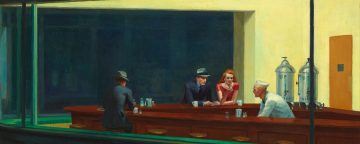

We run the risk of ethical dissolution, too, for although we cannot sever our essences from our appearances, we can indeed create a distance between them. For this we do not need Dorian Gray’s incantation. We have the witchcraft of social media to answer our own prayers — prayers that we might seem to be whatever self we wish to represent, the truth of ourselves hidden away. These mediating social sites and screens dissociate us inwardly, detaching the self from a performed image. And they dissociate us outwardly, detaching us from others by eliminating physical proximity — allowing us to forget others’ humanity, to remove ourselves from the shared scene in which we are all ethical actors.

More here.