Matthew Herper in Stat:

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The data show that the company’s test can detect cancer in the blood with relatively few false positives and that it is fairly accurate at identifying where in the body the tumor was found. Another abstract seems to show that the test is more likely to identify tumors if they are more deadly. One big worry with a cancer blood test is that it would lead to large numbers of patients being diagnosed with mild tumors that would be better off untreated.

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The data show that the company’s test can detect cancer in the blood with relatively few false positives and that it is fairly accurate at identifying where in the body the tumor was found. Another abstract seems to show that the test is more likely to identify tumors if they are more deadly. One big worry with a cancer blood test is that it would lead to large numbers of patients being diagnosed with mild tumors that would be better off untreated.

…Grail is running a preliminary study called the Circulating Cell-Free Genome Atlas (CCGA), which is being conducted in 15,000 patients. The goal from the beginning was to use this study to optimize a diagnostic test. This would then be tested in two more studies: one of 100,000 women enrolled at the time of their first mammogram, and a second of 50,000 men and women between the ages of 50 and 77 in London who have not been diagnosed with cancer. These huge studies are one reason Grail has raised so much money. But the data being reported at the ASCO meeting are from a tiny sliver of that first study: an initial analysis of 2,301 participants from the training phase of the sub-study, including 1,422 people known to have cancer and 879 who have not been diagnosed. These data are being used to pick exactly what test Grail will run.

More here.

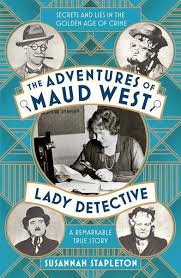

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers.

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers. The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio.

The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio. Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review:

Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review: Matteo Pucciarelli in New Left Review:

Matteo Pucciarelli in New Left Review: Joe Humphreys in The Irish Times:

Joe Humphreys in The Irish Times: Dan Bessner in The New Republic:

Dan Bessner in The New Republic: It’s the question on every cancer patient’s mind: How long have I got? Genomicist

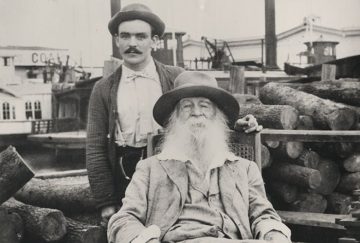

It’s the question on every cancer patient’s mind: How long have I got? Genomicist  “Whitman demonstrates part of his Americanness by placing cocksucking at the center of Leaves of Grass.” Gay liberationist Charles Shively—not one to mince words—wrote this in Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working Class Camerados (1987), his revelatory, if sometimes risible, account of the poet’s queer egalitarianism. Whether cocksucking is central to Whitman’s book, or even uniquely American, is debatable; more pertinent is the implied connection between Whitman’s homosexuality and his patriotic fervor.

“Whitman demonstrates part of his Americanness by placing cocksucking at the center of Leaves of Grass.” Gay liberationist Charles Shively—not one to mince words—wrote this in Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working Class Camerados (1987), his revelatory, if sometimes risible, account of the poet’s queer egalitarianism. Whether cocksucking is central to Whitman’s book, or even uniquely American, is debatable; more pertinent is the implied connection between Whitman’s homosexuality and his patriotic fervor.

Commentators from across the political spectrum warn us that extreme partisan polarization is dissolving all bases for political cooperation, thereby undermining our democracy. The near total consensus on this point is suspicious. A recent Pew study finds that although citizens want politicians to compromise more, they tend to blame only their political opponents for the deadlock. In calling for conciliation, they seek capitulation from the other side. The warnings about polarization might themselves be displays of polarization.

Commentators from across the political spectrum warn us that extreme partisan polarization is dissolving all bases for political cooperation, thereby undermining our democracy. The near total consensus on this point is suspicious. A recent Pew study finds that although citizens want politicians to compromise more, they tend to blame only their political opponents for the deadlock. In calling for conciliation, they seek capitulation from the other side. The warnings about polarization might themselves be displays of polarization. The movie that made me consider filmmaking, the movie that showed me how a director does what he does, how a director can control a movie through his camera, is Once Upon a Time in the West. It was almost like a film school in a movie. It really illustrated how to make an impact as a filmmaker. How to give your work a signature. I found myself completely fascinated, thinking: ‘That’s how you do it.’ It ended up creating an aesthetic in my mind.

The movie that made me consider filmmaking, the movie that showed me how a director does what he does, how a director can control a movie through his camera, is Once Upon a Time in the West. It was almost like a film school in a movie. It really illustrated how to make an impact as a filmmaker. How to give your work a signature. I found myself completely fascinated, thinking: ‘That’s how you do it.’ It ended up creating an aesthetic in my mind.