Madeleine Watts at Literary Hub:

In some respects this reflects a national pathology. Unlike an American or British child, an Australian student can go through thirteen years of education without reading much of their country’s literature at all (of the more than twenty writers I studied in high school, only two were Australian). This is symptomatic of the country’s famed “cultural cringe,” a term first coined in the 1940s by the critic A.A. Phillips to describe the ways that Australians tend to be prejudiced against home-grown art and ideas in favor of those imported from the UK and America. Australia’s attitude to the arts has, for much of the last two centuries, been moral. “What these idiots didn’t realize about White was that he was the most powerful spruiker for morality that anybody was going to read in an Australian work,” argued David Marr, White’s biographer, during a talk at the Wheeler Centre in 2013. “And here were these petty little would-be moral tyrants whinging about this man whose greatest message about this country in the end was that we are an unprincipled people.”

In some respects this reflects a national pathology. Unlike an American or British child, an Australian student can go through thirteen years of education without reading much of their country’s literature at all (of the more than twenty writers I studied in high school, only two were Australian). This is symptomatic of the country’s famed “cultural cringe,” a term first coined in the 1940s by the critic A.A. Phillips to describe the ways that Australians tend to be prejudiced against home-grown art and ideas in favor of those imported from the UK and America. Australia’s attitude to the arts has, for much of the last two centuries, been moral. “What these idiots didn’t realize about White was that he was the most powerful spruiker for morality that anybody was going to read in an Australian work,” argued David Marr, White’s biographer, during a talk at the Wheeler Centre in 2013. “And here were these petty little would-be moral tyrants whinging about this man whose greatest message about this country in the end was that we are an unprincipled people.”

But if White could critique the country and name Australians as unprincipled, it was something he had earned by going back.

more here.

My god, isn’t it fun to read Eve Babitz? Just holding one of her books in your hand is like being in on a good secret. Babitz knows all the good secrets—about Los Angeles, charismatic men, and supposedly glamorous industries like film, music, and magazines. Cool beyond belief but friendly and unintimidating, Babitz hung out with all the best rock stars, directors, and artists of several decades. And she wrote just as lovingly about the rest of LA—the broad world that exists outside the bubble of “the Industry.” Thanks to New York Review Books putting together a collection of this work, we are lucky enough to have more of Babitz’s writing to read.

My god, isn’t it fun to read Eve Babitz? Just holding one of her books in your hand is like being in on a good secret. Babitz knows all the good secrets—about Los Angeles, charismatic men, and supposedly glamorous industries like film, music, and magazines. Cool beyond belief but friendly and unintimidating, Babitz hung out with all the best rock stars, directors, and artists of several decades. And she wrote just as lovingly about the rest of LA—the broad world that exists outside the bubble of “the Industry.” Thanks to New York Review Books putting together a collection of this work, we are lucky enough to have more of Babitz’s writing to read. Can a museum devoted to modernism survive the death of the movement? Can it bring that death about? Ever since the beginnings of the Renaissance in the 14th century, most art movements have lasted one generation, sometimes two. Today, after more than 130 years, modernism is, at least by some measures, insanely and incongruously popular — a world brand. The first thing oligarchs do to signal sophistication, and to cleanse and store money, is collect and build personal museums of modern art, and there’s nothing museumgoers love more than a survey of a mid-century giant. In the U.S., modernism represents the triumph of American greatness and wealth, and it is considered the height of 20th-century European culture — which Americans bought and brought over (which is to say, poached).

Can a museum devoted to modernism survive the death of the movement? Can it bring that death about? Ever since the beginnings of the Renaissance in the 14th century, most art movements have lasted one generation, sometimes two. Today, after more than 130 years, modernism is, at least by some measures, insanely and incongruously popular — a world brand. The first thing oligarchs do to signal sophistication, and to cleanse and store money, is collect and build personal museums of modern art, and there’s nothing museumgoers love more than a survey of a mid-century giant. In the U.S., modernism represents the triumph of American greatness and wealth, and it is considered the height of 20th-century European culture — which Americans bought and brought over (which is to say, poached). The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly eats only milkweed, a poisonous plant that should kill it. The caterpillars thrive on the plant, even storing its toxins in their bodies as a defense against hungry birds. For decades, scientists have marveled at this adaptation. On Thursday, a team of researchers announced they had pinpointed the key evolutionary steps that led to it. Only three genetic mutations

The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly eats only milkweed, a poisonous plant that should kill it. The caterpillars thrive on the plant, even storing its toxins in their bodies as a defense against hungry birds. For decades, scientists have marveled at this adaptation. On Thursday, a team of researchers announced they had pinpointed the key evolutionary steps that led to it. Only three genetic mutations  Now, you may be thinking, “Fuck those guys and the private jets they rode in on.” Fair enough. But here’s the thing: those guys are already fucked. Really. They worked like hell to get where they are—and they’ve got access to more wealth than 99.999 percent of the human beings who have ever lived—but they’re still not where they think they need to be. Without a fundamental change in the way they approach their lives, they’ll never reach their ever-receding goals. And if the futility of their situation ever dawns on them like a dark sunrise, they’re unlikely to receive a lot of sympathy from their friends and family.

Now, you may be thinking, “Fuck those guys and the private jets they rode in on.” Fair enough. But here’s the thing: those guys are already fucked. Really. They worked like hell to get where they are—and they’ve got access to more wealth than 99.999 percent of the human beings who have ever lived—but they’re still not where they think they need to be. Without a fundamental change in the way they approach their lives, they’ll never reach their ever-receding goals. And if the futility of their situation ever dawns on them like a dark sunrise, they’re unlikely to receive a lot of sympathy from their friends and family. Since at least the Great Recession a decade ago, borrowers, activists and others have been building a case that erasing debt acquired during students college years is a matter of economic justice. More recently, researchers have found that canceling some or all of the nation’s outstanding student debt has the potential to boost gross domestic product, narrow the widening racial wealth gap and liberate millions of Americans from a financial albatross that previous generations never had to contend with.

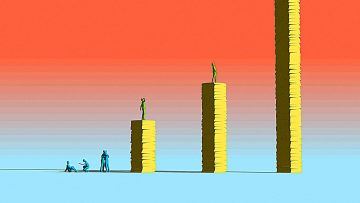

Since at least the Great Recession a decade ago, borrowers, activists and others have been building a case that erasing debt acquired during students college years is a matter of economic justice. More recently, researchers have found that canceling some or all of the nation’s outstanding student debt has the potential to boost gross domestic product, narrow the widening racial wealth gap and liberate millions of Americans from a financial albatross that previous generations never had to contend with. In 1958, sociologist Michael Young wrote a dark satire called The Rise of the Meritocracy. The term “meritocracy” was Young’s own coining, and he chose it to denote a new aristocracy based on expertise and test-taking instead of breeding and titles. In Young’s book, set in 2034, Britain is forced to evolve by international economic competition. The elevation of IQ over birth first serves as a democratizing force championed by socialists, but ultimately results in a rigid caste system. The state uses universal testing to identify and elevate meritocrats, leaving most of England’s citizens poor and demoralized, without even a legitimate grievance, since, after all, who could argue that the wise should not rule? Eventually, a populist movement emerges. The story ends in bloody revolt and the assassination of the fictional author before he can review his page proofs.

In 1958, sociologist Michael Young wrote a dark satire called The Rise of the Meritocracy. The term “meritocracy” was Young’s own coining, and he chose it to denote a new aristocracy based on expertise and test-taking instead of breeding and titles. In Young’s book, set in 2034, Britain is forced to evolve by international economic competition. The elevation of IQ over birth first serves as a democratizing force championed by socialists, but ultimately results in a rigid caste system. The state uses universal testing to identify and elevate meritocrats, leaving most of England’s citizens poor and demoralized, without even a legitimate grievance, since, after all, who could argue that the wise should not rule? Eventually, a populist movement emerges. The story ends in bloody revolt and the assassination of the fictional author before he can review his page proofs.

Affective computing systems are being developed to recognize, interpret, and process human experiences and emotions. They all rely on extensive human behavioral data, captured by various kinds of hardware and processed by an array of sophisticated machine learning software applications.

Affective computing systems are being developed to recognize, interpret, and process human experiences and emotions. They all rely on extensive human behavioral data, captured by various kinds of hardware and processed by an array of sophisticated machine learning software applications. Twelve years, or so the scientists told us in 2018, which means now we are down to eleven. That’s how long we have to pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe by constraining global warming to a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Eleven years to prevent the annihilation of coral reefs, greater melting of the permafrost, and species apocalypse, along with the most dire consequences for human civilization as we know it. Food shortages, forest fires, droughts and monsoons, intensified war and conflict, billions of refugees—we have barely begun to conceive of the range of dystopian futures looming on the horizon.

Twelve years, or so the scientists told us in 2018, which means now we are down to eleven. That’s how long we have to pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe by constraining global warming to a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Eleven years to prevent the annihilation of coral reefs, greater melting of the permafrost, and species apocalypse, along with the most dire consequences for human civilization as we know it. Food shortages, forest fires, droughts and monsoons, intensified war and conflict, billions of refugees—we have barely begun to conceive of the range of dystopian futures looming on the horizon. ONE OF THE GREAT PERVERSITIES

ONE OF THE GREAT PERVERSITIES It would be hard to overestimate the significance of Freud’s The Ego and the Id for psychoanalytic theory and practice. This landmark essay has also enjoyed a robust extra-analytic life, giving the rest of us both a useful terminology and a readily apprehended model of the mind’s workings. The ego, id, and superego (the last two terms made their debut in The Ego and the Id) are now inescapably part of popular culture and learned discourse, political commentary and everyday talk.

It would be hard to overestimate the significance of Freud’s The Ego and the Id for psychoanalytic theory and practice. This landmark essay has also enjoyed a robust extra-analytic life, giving the rest of us both a useful terminology and a readily apprehended model of the mind’s workings. The ego, id, and superego (the last two terms made their debut in The Ego and the Id) are now inescapably part of popular culture and learned discourse, political commentary and everyday talk. Y

Y In Kirkpatrick’s work, Sartre appears far more in need of Beauvoir than Beauvoir is of him. In his later life in particular, it is hard to see him as anything other than pathetic: ruined by alcohol and amphetamines, throwing himself down the intellectual dead-end of Maoism, still skirt-chasing even after several strokes. Much of what is considered to be Sartre’s unique contribution to philosophy and ethics turns out – on consultation of Beauvoir’s letters, diaries and published work – to have started with her.

In Kirkpatrick’s work, Sartre appears far more in need of Beauvoir than Beauvoir is of him. In his later life in particular, it is hard to see him as anything other than pathetic: ruined by alcohol and amphetamines, throwing himself down the intellectual dead-end of Maoism, still skirt-chasing even after several strokes. Much of what is considered to be Sartre’s unique contribution to philosophy and ethics turns out – on consultation of Beauvoir’s letters, diaries and published work – to have started with her.