Azra Raza in the Wall Street Journal:

Most patients continue to face excruciating, costly and ineffective treatments. It’s time to shift our focus from fighting the disease in its last stages to finding the very first cells.

I have been studying and treating cancer for 35 years, and here’s what I know about the progress made in that time: There has been far less than it appears. Despite some advances, the treatments for most kinds of cancer continue to be too painful, too damaging, too expensive and too ineffective. The same three methods—surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy—have prevailed for a half-century.

Consider acute myeloid leukemia, the bone-marrow malignancy that is my specialty. AML accounts for a third of all leukemia cases. Currently, the average age of diagnosis is 68; roughly 11,000 individuals die annually from the disease. The five-year survival rate for diagnosed adults is 24%, and a bone-marrow transplant increases the odds to 50% at best. These figures have hardly budged since the 1970s.

The overall rate of cancer deaths in the U.S. has fallen by a quarter since its peak in 1991, translating to 2.4 million lives saved—but improved treatments are not the primary reason. Rather, a reduction in smoking and improvements in screening have led to 36% fewer deaths for some of the most common cancers—lung, colorectal, breast and prostate. And for all those gains, overall cancer death rates are not dramatically different from what they were in the 1930s, before they rose along with cigarette use. Meanwhile, cancer drug costs are spiraling out of control, projected to exceed $150 billion by next year. With the newest immunotherapies costing millions, the current cancer-treatment paradigm is fast becoming unsupportable. Read more »

Artificial intelligence is better than humans at playing chess or go, but still has trouble holding a conversation or driving a car. A simple way to think about the discrepancy is through the lens of “common sense” — there are features of the world, from the fact that tables are solid to the prediction that a tree won’t walk across the street, that humans take for granted but that machines have difficulty learning. Melanie Mitchell is a computer scientist and complexity researcher who has written a new book about the prospects of modern AI. We talk about deep learning and other AI strategies, why they currently fall short at equipping computers with a functional “folk physics” understanding of the world, and how we might move forward.

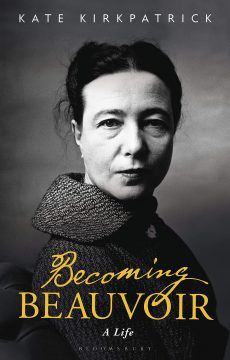

Artificial intelligence is better than humans at playing chess or go, but still has trouble holding a conversation or driving a car. A simple way to think about the discrepancy is through the lens of “common sense” — there are features of the world, from the fact that tables are solid to the prediction that a tree won’t walk across the street, that humans take for granted but that machines have difficulty learning. Melanie Mitchell is a computer scientist and complexity researcher who has written a new book about the prospects of modern AI. We talk about deep learning and other AI strategies, why they currently fall short at equipping computers with a functional “folk physics” understanding of the world, and how we might move forward. Writers always have to make difficult choices about what to leave in and what to cut from their work. The choices become especially acute when a writer is telling her own story. “What an odd thing a diary is,” a character in Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Woman Destroyed (La Femme rompue, 1967) says, “the things you omit are more important than those you put in.”

Writers always have to make difficult choices about what to leave in and what to cut from their work. The choices become especially acute when a writer is telling her own story. “What an odd thing a diary is,” a character in Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Woman Destroyed (La Femme rompue, 1967) says, “the things you omit are more important than those you put in.” In a bone-picking mood,

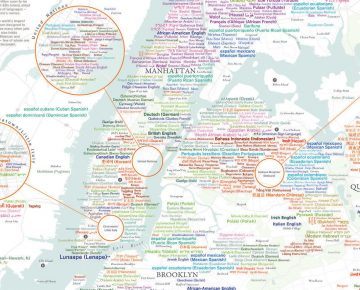

In a bone-picking mood, Reawakening dormant languages requires extraordinary acts of coordination—administrative, social, and emotional—but it is possible. Take jessie “little doe” baird, a Wôpanâak woman who, when pregnant with her fifth child, Mae Alice, had a vision of reviving her ancestral language—the first tongue the Pilgrims encountered in coastal Massachusetts, which had been without speakers for more than a century. baird studied linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then spent the next twenty-six years leading a revival of Wôpanâak; Mae Alice is the first Wôpanâak-speaking child in generations. In Ohio, activist Daryl Baldwin has spearheaded the revival of Myaamia, dormant since the 1960s, first teaching it to himself, his wife, and their four children. Common to both community-led efforts was meticulous linguistic research that fed into the creation of immersion programs focused on fostering fluent new speakers.

Reawakening dormant languages requires extraordinary acts of coordination—administrative, social, and emotional—but it is possible. Take jessie “little doe” baird, a Wôpanâak woman who, when pregnant with her fifth child, Mae Alice, had a vision of reviving her ancestral language—the first tongue the Pilgrims encountered in coastal Massachusetts, which had been without speakers for more than a century. baird studied linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then spent the next twenty-six years leading a revival of Wôpanâak; Mae Alice is the first Wôpanâak-speaking child in generations. In Ohio, activist Daryl Baldwin has spearheaded the revival of Myaamia, dormant since the 1960s, first teaching it to himself, his wife, and their four children. Common to both community-led efforts was meticulous linguistic research that fed into the creation of immersion programs focused on fostering fluent new speakers. What does Theroux do on his trip? In Nogales he has his teeth whitened, in San Diego de la Unión he attends a first communion, in San Miguel de Allende he drops in on a wedding and in Monte Albán he inspects pyramids built at a time when ‘Britain was a land of quarrelsome Iron Age tribes painting their bellies blue and huddled in hill forts’. Sometimes he abandons his car, which has Massachusetts plates, in a secure car park and goes on bus journeys. Mexican highways are well maintained, he notes, but the off-ramp ‘always leads to the dusty antique past – to the man plowing a stony field with a burro, to the woman with a bundle on her head, to the boy herding goats, to the ranchitos, the carne asada stands, the five-hundred-year-old churches, and a tienda, selling beer and snacks, with a skinny cat asleep on the tamales’.

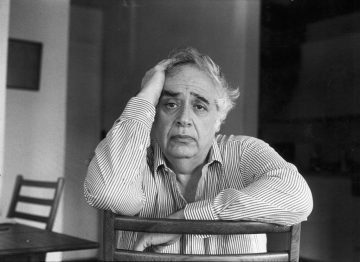

What does Theroux do on his trip? In Nogales he has his teeth whitened, in San Diego de la Unión he attends a first communion, in San Miguel de Allende he drops in on a wedding and in Monte Albán he inspects pyramids built at a time when ‘Britain was a land of quarrelsome Iron Age tribes painting their bellies blue and huddled in hill forts’. Sometimes he abandons his car, which has Massachusetts plates, in a secure car park and goes on bus journeys. Mexican highways are well maintained, he notes, but the off-ramp ‘always leads to the dusty antique past – to the man plowing a stony field with a burro, to the woman with a bundle on her head, to the boy herding goats, to the ranchitos, the carne asada stands, the five-hundred-year-old churches, and a tienda, selling beer and snacks, with a skinny cat asleep on the tamales’. Harold Bloom, the prodigious literary critic who championed and defended the Western canon in an outpouring of influential books that appeared not only on college syllabuses but also — unusual for an academic — on best-seller lists, died on Monday at a hospital in New Haven. He was 89. His death was confirmed by his wife, Jeanne Bloom, who said he taught his last class at Yale University on Thursday. Professor Bloom was frequently called the most notorious literary critic in America. From a vaunted perch at Yale, he flew in the face of almost every trend in the literary criticism of his day. Chiefly he argued for the literary superiority of the Western giants like Shakespeare, Chaucer and Kafka — all of them white and male, his own critics pointed out — over writers favored by what he called “the School of Resentment,” by which he meant multiculturalists, feminists, Marxists, neoconservatives and others whom he saw as betraying literature’s essential purpose. “He is, by any reckoning, one of the most stimulating literary presences of the last half-century — and the most protean,”

Harold Bloom, the prodigious literary critic who championed and defended the Western canon in an outpouring of influential books that appeared not only on college syllabuses but also — unusual for an academic — on best-seller lists, died on Monday at a hospital in New Haven. He was 89. His death was confirmed by his wife, Jeanne Bloom, who said he taught his last class at Yale University on Thursday. Professor Bloom was frequently called the most notorious literary critic in America. From a vaunted perch at Yale, he flew in the face of almost every trend in the literary criticism of his day. Chiefly he argued for the literary superiority of the Western giants like Shakespeare, Chaucer and Kafka — all of them white and male, his own critics pointed out — over writers favored by what he called “the School of Resentment,” by which he meant multiculturalists, feminists, Marxists, neoconservatives and others whom he saw as betraying literature’s essential purpose. “He is, by any reckoning, one of the most stimulating literary presences of the last half-century — and the most protean,”  The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) latest foray into turning emerging technologies into useful data sets is focusing on how the body’s trillions of cells interconnect and interact. The

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) latest foray into turning emerging technologies into useful data sets is focusing on how the body’s trillions of cells interconnect and interact. The

Vladimir Nabokov was not only being contrarian when he came out against the theory of evolution. He really meant it. “Natural selection in the Darwinian sense,” he wrote, “could not explain the miraculous coincidence of imitative aspect and imitative behavior, nor could one appeal to the theory of ‘the struggle for life’ when a protective device was carried to a point of mimetic subtlety, exuberance, and luxury far in excess of a predator’s power of appreciation.”

Vladimir Nabokov was not only being contrarian when he came out against the theory of evolution. He really meant it. “Natural selection in the Darwinian sense,” he wrote, “could not explain the miraculous coincidence of imitative aspect and imitative behavior, nor could one appeal to the theory of ‘the struggle for life’ when a protective device was carried to a point of mimetic subtlety, exuberance, and luxury far in excess of a predator’s power of appreciation.” Daniella Hodgson is digging a hole in the sand on a windswept beach as seabirds wheel overhead. “Found one,” she cries, flinging down her spade. She opens her hand to reveal a wriggling lugworm. Plucked from its underground burrow, this humble creature is not unlike the proverbial canary in a coal mine. A sentinel for plastic, the worm will ingest any particles of plastic it comes across while swallowing sand, which can then pass up the food chain to birds and fish. “We want to see how much plastic the island is potentially getting on its shores – so what is in the sediments there – and what the animals are eating,” says Ms Hodgson, a postgraduate researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London. “If you’re exposed to more plastics are you going to be eating more plastics? What types of plastics, what shapes, colours, sizes? And then we can use that kind of information to inform experiments to look at the impacts of ingesting those plastics on different animals.”

Daniella Hodgson is digging a hole in the sand on a windswept beach as seabirds wheel overhead. “Found one,” she cries, flinging down her spade. She opens her hand to reveal a wriggling lugworm. Plucked from its underground burrow, this humble creature is not unlike the proverbial canary in a coal mine. A sentinel for plastic, the worm will ingest any particles of plastic it comes across while swallowing sand, which can then pass up the food chain to birds and fish. “We want to see how much plastic the island is potentially getting on its shores – so what is in the sediments there – and what the animals are eating,” says Ms Hodgson, a postgraduate researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London. “If you’re exposed to more plastics are you going to be eating more plastics? What types of plastics, what shapes, colours, sizes? And then we can use that kind of information to inform experiments to look at the impacts of ingesting those plastics on different animals.” I honestly don’t know where to begin with this whole thing. But let me start by making clear what I am not saying. I am not saying that we should not read Handke’s literary work. My objection is not a version of the age-old question of whether we should listen to Richard Wagner. Go ahead and listen to Wagner. Go ahead and read Handke. My point is this: It is one thing to read him — it is quite another to bestow upon him a prize that delivers a great amount of legitimacy to his entire body of work, not just the novels and plays that are most impeccable and nonpolitical.

I honestly don’t know where to begin with this whole thing. But let me start by making clear what I am not saying. I am not saying that we should not read Handke’s literary work. My objection is not a version of the age-old question of whether we should listen to Richard Wagner. Go ahead and listen to Wagner. Go ahead and read Handke. My point is this: It is one thing to read him — it is quite another to bestow upon him a prize that delivers a great amount of legitimacy to his entire body of work, not just the novels and plays that are most impeccable and nonpolitical. I’ve received tenure at Harvard!

I’ve received tenure at Harvard! Where in the pantheon

Where in the pantheon