Ben Juers at Sydney Review of Books:

Terry Eagleton’s Humour and Peter Timms’ Silliness: A Serious History are two recent additions to the patchy field of humour studies. Both authors are hemmed into the Anglocentric comedy canon that sees absurdist comedy peaking with The Goon Show, Pete and Dud, and Monty Python, and going downhill ever since. They’re also both in their seventies. This puts you in the weird position of feeling unreasonable for expecting them to be up-to-date on their subject. But neither would you want their lukewarm take on, say, ‘meme commentator’ @gayvapeshark or the HBO series Los Espookys.

Terry Eagleton’s Humour and Peter Timms’ Silliness: A Serious History are two recent additions to the patchy field of humour studies. Both authors are hemmed into the Anglocentric comedy canon that sees absurdist comedy peaking with The Goon Show, Pete and Dud, and Monty Python, and going downhill ever since. They’re also both in their seventies. This puts you in the weird position of feeling unreasonable for expecting them to be up-to-date on their subject. But neither would you want their lukewarm take on, say, ‘meme commentator’ @gayvapeshark or the HBO series Los Espookys.

To be fair, cutting-edge relevancy isn’t Eagleton or Timms’ priority. Humour is a critical survey not of humour but its theory – like a literature review for a PhD, albeit more reader-friendly. Its most interesting aspect is its Marxist subtext (Eagleton’s famously a comrade), which occasionally breaks ground but never erupts into a full-blown theory of how humour can serve Leftist aims.

more here.

First, a warning: this is a life-changing book and will alter your relationship to food for ever. I can’t imagine anyone reading Safran Foer’s lucid, heartfelt, deeply compassionate prose and then reaching blithely for a cheeseburger. There’s some dispute as to precisely what proportion of global heating is directly related to the rearing of animals for food, but even the lowest estimates put it on a par with the entire global transportation industry. A well-evidenced

First, a warning: this is a life-changing book and will alter your relationship to food for ever. I can’t imagine anyone reading Safran Foer’s lucid, heartfelt, deeply compassionate prose and then reaching blithely for a cheeseburger. There’s some dispute as to precisely what proportion of global heating is directly related to the rearing of animals for food, but even the lowest estimates put it on a par with the entire global transportation industry. A well-evidenced  An interview with Vinayak Chaturdevi in Jacobin:

An interview with Vinayak Chaturdevi in Jacobin: Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein in TNR:

Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein in TNR: Gabriel Winant in n+1:

Gabriel Winant in n+1: Troy Vettese in Boston Review:

Troy Vettese in Boston Review: Consciousness of time passing seldom accords with what clocks and calendars tell us. The discord is especially acute in these days of Trump-induced, ever changing “breaking news.” Thus, it seems to me and I suspect to every other sentient being paying attention, that it was centuries ago that Donald Trump was still making an effort not to flaunt his ignorance and mindlessness. As far as the physics goes, it hasn’t been quite three years. It seems like centuries ago too when there were still “adults in the room,” trying, without much success, to keep Trump from acting out too egregiously or doing anything too transparently stupid. According to the calendar, it has not been much more than a year since most of that stable cleared out. Among those adults, there was a retired Marine Corps General called “Mad Dog,” an Exxon-Mobil honcho named “Rex,” and H. R. McMaster, a retired Army Lieutenant General. They were Trump’s Defense Secretary, Secretary of State, and National Security Advisor, respectively.

Consciousness of time passing seldom accords with what clocks and calendars tell us. The discord is especially acute in these days of Trump-induced, ever changing “breaking news.” Thus, it seems to me and I suspect to every other sentient being paying attention, that it was centuries ago that Donald Trump was still making an effort not to flaunt his ignorance and mindlessness. As far as the physics goes, it hasn’t been quite three years. It seems like centuries ago too when there were still “adults in the room,” trying, without much success, to keep Trump from acting out too egregiously or doing anything too transparently stupid. According to the calendar, it has not been much more than a year since most of that stable cleared out. Among those adults, there was a retired Marine Corps General called “Mad Dog,” an Exxon-Mobil honcho named “Rex,” and H. R. McMaster, a retired Army Lieutenant General. They were Trump’s Defense Secretary, Secretary of State, and National Security Advisor, respectively. In the early 2000s,

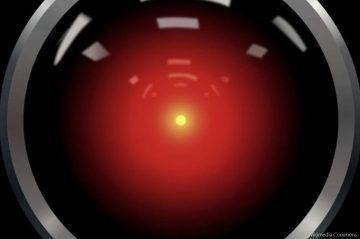

In the early 2000s,  In 2017, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University shocked the gaming world when they programmed a computer to beat experts in a poker game called no-limit hold ’em. People assumed a poker player’s intuition and creative thinking would give him or her the competitive edge. Yet by playing 24 trillion hands of poker every second for two months, the computer “taught” itself an unbeatable strategy.

In 2017, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University shocked the gaming world when they programmed a computer to beat experts in a poker game called no-limit hold ’em. People assumed a poker player’s intuition and creative thinking would give him or her the competitive edge. Yet by playing 24 trillion hands of poker every second for two months, the computer “taught” itself an unbeatable strategy. Lord Byron, according to his dumped mistress Lady Caroline Lamb, was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Antony Peattie’s exploration of his personal caprices and intellectual quirks definitively strikes down all three charges. Byron the self-aware ironist was never demented; he may have relished his reputation for vice, but his pagan promiscuity was overshadowed by the legacy of his punitive Calvinist upbringing; and it would surely have been a delight, not a danger, to know this convivial fellow, whose eyes, as Coleridge said, were “the open portals of the sun” and his teeth “so many stationary smiles”.

Lord Byron, according to his dumped mistress Lady Caroline Lamb, was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Antony Peattie’s exploration of his personal caprices and intellectual quirks definitively strikes down all three charges. Byron the self-aware ironist was never demented; he may have relished his reputation for vice, but his pagan promiscuity was overshadowed by the legacy of his punitive Calvinist upbringing; and it would surely have been a delight, not a danger, to know this convivial fellow, whose eyes, as Coleridge said, were “the open portals of the sun” and his teeth “so many stationary smiles”. The four impossible “problems of antiquity”—

The four impossible “problems of antiquity”— Silence and endings are much on Howe’s mind these days. She is seventy-nine, slight but still spry, with a kind, angular face and sharp blue eyes. She has a puckish sense of humor: her friend, the philosopher Richard Kearney, described her to me as a “comic mystic, or a mystic comic.” The coffee shop I originally suggested was closed for the day. On our walk to the Fogg, she told me, in a voice that still recalls the 1950s Cambridge milieu in which she grew up, about her recent trip to Belfast and how much she’d loved

Silence and endings are much on Howe’s mind these days. She is seventy-nine, slight but still spry, with a kind, angular face and sharp blue eyes. She has a puckish sense of humor: her friend, the philosopher Richard Kearney, described her to me as a “comic mystic, or a mystic comic.” The coffee shop I originally suggested was closed for the day. On our walk to the Fogg, she told me, in a voice that still recalls the 1950s Cambridge milieu in which she grew up, about her recent trip to Belfast and how much she’d loved

I’ve been saying it for years! Every fall, the big night would come and I would set my alarm for four or six or eight in the morning, depending on my time zone, and then not sleep because I was sure Olga Tokarczuk would win the Nobel Prize in Literature. This year it happened! At 4 A.M.

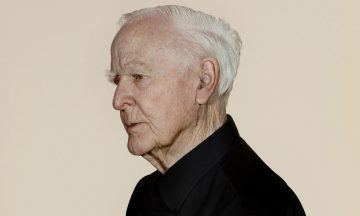

I’ve been saying it for years! Every fall, the big night would come and I would set my alarm for four or six or eight in the morning, depending on my time zone, and then not sleep because I was sure Olga Tokarczuk would win the Nobel Prize in Literature. This year it happened! At 4 A.M. I have always admired John le Carré. Not always without envy – so many bestsellers! – but in wonderment at the fact that the work of an artist of such high literary accomplishment should have achieved such wide appeal among readers. That le Carré, otherwise David Cornwell, has chosen to set his novels almost exclusively in the world of espionage has allowed certain critics to dismiss him as essentially unserious, a mere entertainer. But with at least two of his books,

I have always admired John le Carré. Not always without envy – so many bestsellers! – but in wonderment at the fact that the work of an artist of such high literary accomplishment should have achieved such wide appeal among readers. That le Carré, otherwise David Cornwell, has chosen to set his novels almost exclusively in the world of espionage has allowed certain critics to dismiss him as essentially unserious, a mere entertainer. But with at least two of his books,  A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Such an event hasn’t actually happened, but the potential for sabotaging AI is very real. Researchers have already demonstrated

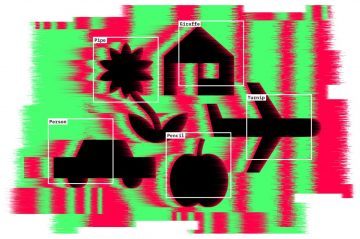

A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Such an event hasn’t actually happened, but the potential for sabotaging AI is very real. Researchers have already demonstrated