Hettie O’Brien in New Statesman:

The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”. Writing in 1973, Gorz was frustrated by a paradox: cars had once been a luxury, invented to provide the wealthy with the unprecedented privilege of travelling much faster than everyone else. But they later became a necessity – objects considered so vital that people were willing to take on debt to acquire them. “This practical devaluation has not yet been followed by an ideological devaluation,” Gorz observed. Cars are still treated as a “sacred cow” – rather than an antisocial product.

The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”. Writing in 1973, Gorz was frustrated by a paradox: cars had once been a luxury, invented to provide the wealthy with the unprecedented privilege of travelling much faster than everyone else. But they later became a necessity – objects considered so vital that people were willing to take on debt to acquire them. “This practical devaluation has not yet been followed by an ideological devaluation,” Gorz observed. Cars are still treated as a “sacred cow” – rather than an antisocial product.

Have cars made people happier? As a commuter (one who admittedly can’t drive), I’d argue not. They are an emblem of individualism, represented by former prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s embrace of private car ownership (in 1986, she cut the ribbon on the final stretch of the M25). Whether speeding along cycle paths or seated on a bus, journeying to work in London and many other cities is often slowed – and imperilled – by steel boxes regularly carrying only a single individual. They occupy scarce public space and emit noxious fumes.

More than anything, cars seem increasingly inappropriate in a world endangered by climate change.

More here.

Thomas Piketty’s new book

Thomas Piketty’s new book  Some sporting moments achieve mythical status because of their sheer audacity. Muhammad Ali’s

Some sporting moments achieve mythical status because of their sheer audacity. Muhammad Ali’s As it is becoming obvious that political responses to global warming such as the Paris treaty are not working, environmentalists are urging us to consider the climate impact of our personal actions. Don’t eat meat, don’t drive a gasoline-powered car and don’t fly, they say. But these individual actions won’t make a substantial difference to our planet, and such demands divert attention away from the solutions that are needed.

As it is becoming obvious that political responses to global warming such as the Paris treaty are not working, environmentalists are urging us to consider the climate impact of our personal actions. Don’t eat meat, don’t drive a gasoline-powered car and don’t fly, they say. But these individual actions won’t make a substantial difference to our planet, and such demands divert attention away from the solutions that are needed. How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that.

How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that. Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop. Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,

Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,  In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option.

In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option. FOR THE AUTUMNAL EQUINOX OF 1967

FOR THE AUTUMNAL EQUINOX OF 1967 Of all the ways that human beings differ from the rest of what is found in nature, being able to think is most fundamental. Being able to think is, it seems, uniquely characteristic of us. But what is so special about the ability to think? In other words, what is so special about us? Analytic philosophy finds its foundations in an answer: not very much. An elusive new book, Thinking and Being, by Irad Kimhi, a heretofore little-known Israeli philosopher, argues that this is the wrong answer. And so, he argues, a whole tradition of philosophical thought is wrong, not just in the details, but in the fundamentals. What Kimhi wants to show is that the logical features of thought, and so also the features of those who think them, stand at a far remove from anything we might now call “natural.”

Of all the ways that human beings differ from the rest of what is found in nature, being able to think is most fundamental. Being able to think is, it seems, uniquely characteristic of us. But what is so special about the ability to think? In other words, what is so special about us? Analytic philosophy finds its foundations in an answer: not very much. An elusive new book, Thinking and Being, by Irad Kimhi, a heretofore little-known Israeli philosopher, argues that this is the wrong answer. And so, he argues, a whole tradition of philosophical thought is wrong, not just in the details, but in the fundamentals. What Kimhi wants to show is that the logical features of thought, and so also the features of those who think them, stand at a far remove from anything we might now call “natural.” This shattering, sometimes unbearably powerful novel, completed in 1904, was written by Henrik Pontoppidan, who won the Nobel Prize in 1917. It is considered one of the greatest Danish novels; the filmmaker Bille August turned the story into a nearly three-hour movie called, in English, “A Fortunate Man” (2019). The novel was praised by Thomas Mann and Ernst Bloch, and is effectively at the center of Georg Lukács’s classic study “

This shattering, sometimes unbearably powerful novel, completed in 1904, was written by Henrik Pontoppidan, who won the Nobel Prize in 1917. It is considered one of the greatest Danish novels; the filmmaker Bille August turned the story into a nearly three-hour movie called, in English, “A Fortunate Man” (2019). The novel was praised by Thomas Mann and Ernst Bloch, and is effectively at the center of Georg Lukács’s classic study “

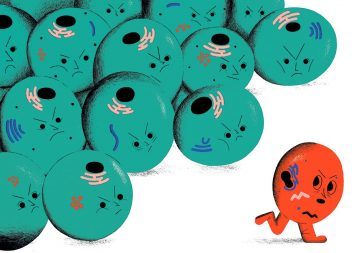

Yasuyaki Fujita has seen first-hand what happens when cells stop being polite and start getting real. He caught a glimpse of this harsh microscopic world when he switched on a cancer-causing gene called Ras in a few kidney cells in a dish. He expected to see the cancerous cells expanding and forming the beginnings of tumours among their neighbours. Instead, the neat, orderly neighbours armed themselves with filament proteins and started “poking, poking, poking”, says Fujita, a cancer biologist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. “The transformed cells were eliminated from the society of normal cells,” he says, literally pushed out by the cells next door.

Yasuyaki Fujita has seen first-hand what happens when cells stop being polite and start getting real. He caught a glimpse of this harsh microscopic world when he switched on a cancer-causing gene called Ras in a few kidney cells in a dish. He expected to see the cancerous cells expanding and forming the beginnings of tumours among their neighbours. Instead, the neat, orderly neighbours armed themselves with filament proteins and started “poking, poking, poking”, says Fujita, a cancer biologist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. “The transformed cells were eliminated from the society of normal cells,” he says, literally pushed out by the cells next door.