by Akim Reinahrdt

Time slips

past us, fast flow,

like a river rushing over gray stones

Time drips

slower than slow

like thick sap hanging from pine cones

I’m not sure time is real. I mean, things happen. Entropy and whatnot. But I don’t know if I accept that measuring the pace of happenings is anything more than a construct.

Don’t get me wrong. I know the world is round, or a close approximation thereof. I’m down with the science. But physicists, as a group, aren’t united on what time is. Something about time being “measured and malleable in relativity while assumed as background (and not an observable) in quantum mechanics.”

So while we experience it as real, it may not be “fundamentally real.”

And that’s kinda how it feels to me.

I remember my 6th grade English teacher, Mrs. Newman (Ms. was not to her liking), telling us that the older you get, the faster time goes by. I’m not sure why, but that idea immediately clung to me. Though I was only 11 years old, or perhaps in part because of it, I got what she was saying. And I believed her. After all, she had lived four or five or six times (who could tell) as long as I had. So even though what she was describing sounded like a cliché passed on from generation to generation, I assumed her own experiences had borne it out. During the four and a half decades since, I have always remembered her words and noticed that, in a general sense, she was absolutely correct. Back then, a summer was endless. Now, the years roll on like a spare tire picking up speed down a hill.

But that is a historical observation I make as I look back. My present, like everyone else’s, stretches and squeezes like an accordion. Read more »

Why do we enjoy showing and sharing?

Why do we enjoy showing and sharing? A theory developed by

A theory developed by  One unfortunate feature of American politics is that both Republicans and Democrats tend to work themselves into a frenzy over the other party’s presidential candidate, no matter who it is. To put it bluntly, both sides cry wolf all the time. Yes, I am a Democrat, but Democrats do this too — I’m old enough to remember when people I knew went crazy over poor old Mitt Romney saying that he had “

One unfortunate feature of American politics is that both Republicans and Democrats tend to work themselves into a frenzy over the other party’s presidential candidate, no matter who it is. To put it bluntly, both sides cry wolf all the time. Yes, I am a Democrat, but Democrats do this too — I’m old enough to remember when people I knew went crazy over poor old Mitt Romney saying that he had “ Greetings, gentle readers! Welcome to the very first installment of Am I the (Literary) Assh*le, a series where I get drunk and answer your burning (anonymous) questions about all things literary.

Greetings, gentle readers! Welcome to the very first installment of Am I the (Literary) Assh*le, a series where I get drunk and answer your burning (anonymous) questions about all things literary. On Monday, tens of millions across

On Monday, tens of millions across  There’s a scene in that modern classic of screwball existentialism,

There’s a scene in that modern classic of screwball existentialism,  DURING A HISTORY

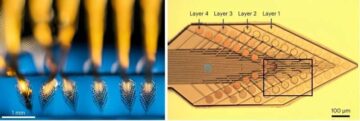

DURING A HISTORY Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information.

Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information.