Yascha Mounk and Martha Nussbaum in Persuasion:

Yascha Mounk: Before we get properly into the different subjects we’ll explore today, what actually is a moral philosophy? And what is the strange enterprise of ethics, and of trying to think about how one should act in the world?

Martha Nussbaum: I’ll first say what most people think it is (I have a rather different view). The general idea started with Socrates, who thought most people don’t pause to think and they don’t summon their beliefs into explicitness and therefore are guided by custom, convention, and authority, and have never stopped to sort out what they really think. So what most people who teach moral philosophy do is just try to conduct that kind of Socratic inquiry, get people to be more critical, more conscious, and, therefore, to discuss with others more in that spirit of critical awareness, rather than just saying, “Oh, I think this.”

Martha Nussbaum: I’ll first say what most people think it is (I have a rather different view). The general idea started with Socrates, who thought most people don’t pause to think and they don’t summon their beliefs into explicitness and therefore are guided by custom, convention, and authority, and have never stopped to sort out what they really think. So what most people who teach moral philosophy do is just try to conduct that kind of Socratic inquiry, get people to be more critical, more conscious, and, therefore, to discuss with others more in that spirit of critical awareness, rather than just saying, “Oh, I think this.”

But I also think that in a pluralistic culture, where people get their ethical views from many different sources, some religious and some secular, we have to be very careful about not pronouncing and not steering in one direction rather than another. And, therefore, I think ethics has got quite narrow constraints. But political philosophy has to try to get to principles that could guide the whole society…

More here.

Since ancient times, plants’ ability to orient their eyeless bodies toward the nearest, brightest source of light — known today as phototropism — has fascinated scholars and generated countless scientific and philosophical debates. And over the past 150 years, botanists have successfully unraveled many of the key molecular pathways that underpin how plants sense light and act on that information.

Since ancient times, plants’ ability to orient their eyeless bodies toward the nearest, brightest source of light — known today as phototropism — has fascinated scholars and generated countless scientific and philosophical debates. And over the past 150 years, botanists have successfully unraveled many of the key molecular pathways that underpin how plants sense light and act on that information. On July 4, 1845, a man from Concord, Massachusetts, declared his own independence and went into the woods nearby. On the shore of a pond there, Henry David Thoreau built a small wooden cabin, which he would call home for two years, two months and two days. From this base he began a philosophical project of “deliberate” living, intending to “earn [a] living by the labor of my hands only”. Though an ostensibly radical undertaking, this experiment was not a break with his past, but the logical culmination of years of searching and groping. Since graduating from Harvard in 1837 Thoreau had tried out many ways of earning his keep, and fortunately proved competent in almost everything he set his mind to. Asked once to describe his professional situation, he responded: “I don’t know whether mine is a profession, or a trade, or what not … I am a schoolmaster, a private tutor, a surveyor, a gardener, a farmer, a painter (I mean a house-painter), a carpenter, a mason, a day-laborer, a pencil-maker, a glass-paper-maker, a writer, and sometimes a poetaster”.

On July 4, 1845, a man from Concord, Massachusetts, declared his own independence and went into the woods nearby. On the shore of a pond there, Henry David Thoreau built a small wooden cabin, which he would call home for two years, two months and two days. From this base he began a philosophical project of “deliberate” living, intending to “earn [a] living by the labor of my hands only”. Though an ostensibly radical undertaking, this experiment was not a break with his past, but the logical culmination of years of searching and groping. Since graduating from Harvard in 1837 Thoreau had tried out many ways of earning his keep, and fortunately proved competent in almost everything he set his mind to. Asked once to describe his professional situation, he responded: “I don’t know whether mine is a profession, or a trade, or what not … I am a schoolmaster, a private tutor, a surveyor, a gardener, a farmer, a painter (I mean a house-painter), a carpenter, a mason, a day-laborer, a pencil-maker, a glass-paper-maker, a writer, and sometimes a poetaster”. For many progressives, it was a big moment. In 2019, Congress was holding its first

For many progressives, it was a big moment. In 2019, Congress was holding its first  Since the late 1970s,

Since the late 1970s, T

T H

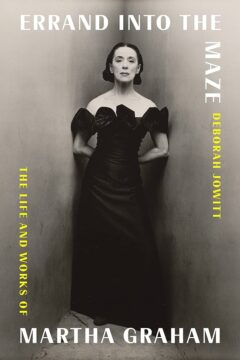

H The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification.

The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification. F

F Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of

Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of