Edgar Dubourg, Valentin Thouzeau, Thomas Beuchot, Constant Bonard, Pascal Boyer, et al, in a new paper:

We hypothesize that fictional stories are highly successful in human cultures partly because they activate evolved cognitive mechanisms, for instance for finding mates (e.g., in romance fiction), exploring the world (e.g., in adventure and speculative fiction), or avoiding predators (e.g., in horror fiction). In this paper, we put forward a comprehensive framework to study fiction through this evolutionary lens.The primary goal of this framework is to carve fictional stories at their cognitive joints using an evolutionary framework. Reviewing a wide range of adaptive variations in human psychology–in personality and developmental psychology, behavioral ecology, and evolutionary biology, among other disciplines –, this framework also addresses the question of interindividual differences in preferences for different features in fictional stories. It generates a wide range of predictions about the patterns of combinations of such features, according to the patterns of variations in the mechanisms triggered by fictional stories. As a result of a highly collaborative effort, we present a comprehensive review of evolved cognitive mechanisms that fictional stories activate.To generate this review, we (1) listed more than 70 adaptive challenges humans faced in the course of their evolution, (2) identified the adaptive psychological mechanisms that evolved in response to such challenges, (3) specified four sources of adaptive variability for the sensitivity of each mechanism(i.e., personality traits, sex, age, and ecological conditions), and (4) linked these mechanisms to the story features that trigger them. This comprehensive framework lays the ground for a theory-driven research program for the study of fictional stories, their content, distribution, structure, and cultural evolution.

We hypothesize that fictional stories are highly successful in human cultures partly because they activate evolved cognitive mechanisms, for instance for finding mates (e.g., in romance fiction), exploring the world (e.g., in adventure and speculative fiction), or avoiding predators (e.g., in horror fiction). In this paper, we put forward a comprehensive framework to study fiction through this evolutionary lens.The primary goal of this framework is to carve fictional stories at their cognitive joints using an evolutionary framework. Reviewing a wide range of adaptive variations in human psychology–in personality and developmental psychology, behavioral ecology, and evolutionary biology, among other disciplines –, this framework also addresses the question of interindividual differences in preferences for different features in fictional stories. It generates a wide range of predictions about the patterns of combinations of such features, according to the patterns of variations in the mechanisms triggered by fictional stories. As a result of a highly collaborative effort, we present a comprehensive review of evolved cognitive mechanisms that fictional stories activate.To generate this review, we (1) listed more than 70 adaptive challenges humans faced in the course of their evolution, (2) identified the adaptive psychological mechanisms that evolved in response to such challenges, (3) specified four sources of adaptive variability for the sensitivity of each mechanism(i.e., personality traits, sex, age, and ecological conditions), and (4) linked these mechanisms to the story features that trigger them. This comprehensive framework lays the ground for a theory-driven research program for the study of fictional stories, their content, distribution, structure, and cultural evolution.

More here.

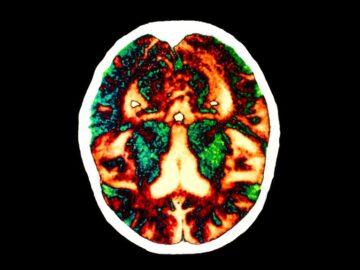

Neuralink was founded in 2016 by Elon Musk, who also runs SpaceX, Tesla and X, formerly Twitter, to create brain-computer interfaces: devices connected to the brain that allow people to communicate with computers by thought alone.

Neuralink was founded in 2016 by Elon Musk, who also runs SpaceX, Tesla and X, formerly Twitter, to create brain-computer interfaces: devices connected to the brain that allow people to communicate with computers by thought alone.

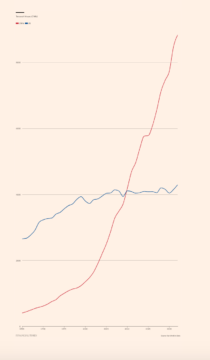

As data from the IEA confirm, the scale of China’s green energy push in the last couple of years dwarfs the much ballyhooed green energy programs in the West – NextGenEU, IRA etc.

As data from the IEA confirm, the scale of China’s green energy push in the last couple of years dwarfs the much ballyhooed green energy programs in the West – NextGenEU, IRA etc. There was a brief period in the later part of the Covid-19 pandemic, between the moment when Glenn Youngkin swept into the Virginia governorship and the full political return of Donald Trump, when I became convinced that American liberalism was headed for a truly epochal defeat in 2024.

There was a brief period in the later part of the Covid-19 pandemic, between the moment when Glenn Youngkin swept into the Virginia governorship and the full political return of Donald Trump, when I became convinced that American liberalism was headed for a truly epochal defeat in 2024. M

M I

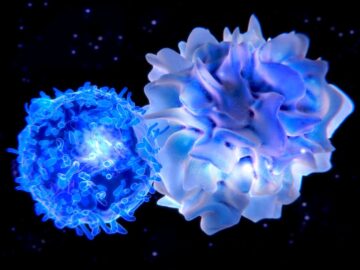

I Back in 2001, immunologist Pere Santamaria was exploring a new way to study diabetes. Working in mice, he and his collaborators developed a method that uses iron oxide nanoparticles to track the key immune cells involved in the disorder.

Back in 2001, immunologist Pere Santamaria was exploring a new way to study diabetes. Working in mice, he and his collaborators developed a method that uses iron oxide nanoparticles to track the key immune cells involved in the disorder. We hypothesize that fictional stories are highly successful in human cultures partly because they activate evolved cognitive mechanisms, for instance for finding mates (e.g., in romance fiction), exploring the world (e.g., in adventure and speculative fiction), or avoiding predators (e.g., in horror fiction). In this paper, we put forward a comprehensive framework to study fiction through this evolutionary lens.The primary goal of this framework is to carve fictional stories at their cognitive joints using an evolutionary framework. Reviewing a wide range of adaptive variations in human psychology–in personality and developmental psychology, behavioral ecology, and evolutionary biology, among other disciplines –, this framework also addresses the question of interindividual differences in preferences for different features in fictional stories. It generates a wide range of predictions about the patterns of combinations of such features, according to the patterns of variations in the mechanisms triggered by fictional stories. As a result of a highly collaborative effort, we present a comprehensive review of evolved cognitive mechanisms that fictional stories activate.To generate this review, we (1) listed more than 70 adaptive challenges humans faced in the course of their evolution, (2) identified the adaptive psychological mechanisms that evolved in response to such challenges, (3) specified four sources of adaptive variability for the sensitivity of each mechanism(i.e., personality traits, sex, age, and ecological conditions), and (4) linked these mechanisms to the story features that trigger them. This comprehensive framework lays the ground for a theory-driven research program for the study of fictional stories, their content, distribution, structure, and cultural evolution.

We hypothesize that fictional stories are highly successful in human cultures partly because they activate evolved cognitive mechanisms, for instance for finding mates (e.g., in romance fiction), exploring the world (e.g., in adventure and speculative fiction), or avoiding predators (e.g., in horror fiction). In this paper, we put forward a comprehensive framework to study fiction through this evolutionary lens.The primary goal of this framework is to carve fictional stories at their cognitive joints using an evolutionary framework. Reviewing a wide range of adaptive variations in human psychology–in personality and developmental psychology, behavioral ecology, and evolutionary biology, among other disciplines –, this framework also addresses the question of interindividual differences in preferences for different features in fictional stories. It generates a wide range of predictions about the patterns of combinations of such features, according to the patterns of variations in the mechanisms triggered by fictional stories. As a result of a highly collaborative effort, we present a comprehensive review of evolved cognitive mechanisms that fictional stories activate.To generate this review, we (1) listed more than 70 adaptive challenges humans faced in the course of their evolution, (2) identified the adaptive psychological mechanisms that evolved in response to such challenges, (3) specified four sources of adaptive variability for the sensitivity of each mechanism(i.e., personality traits, sex, age, and ecological conditions), and (4) linked these mechanisms to the story features that trigger them. This comprehensive framework lays the ground for a theory-driven research program for the study of fictional stories, their content, distribution, structure, and cultural evolution. Some of the largest and most notable prediction markets to date have been around elections. The only problem? Prediction markets simply aren’t very good at political predictions. Markets for major U.S. elections are some of the deepest prediction markets anywhere: billions of dollars bet, millions of daily trades, and huge amounts of press. In theory, the larger the market, the more accurate the predictions. But in the markets with the biggest spotlight, we see a lot of strange stuff. Predictions that don’t line up with common sense. Odds that seem to defy reality. Obviously noncredible market movements. To figure out why, we’ll have to explore the underlying mechanisms that make markets work, and why the typical user of political prediction markets may not behave in the ways we expect.

Some of the largest and most notable prediction markets to date have been around elections. The only problem? Prediction markets simply aren’t very good at political predictions. Markets for major U.S. elections are some of the deepest prediction markets anywhere: billions of dollars bet, millions of daily trades, and huge amounts of press. In theory, the larger the market, the more accurate the predictions. But in the markets with the biggest spotlight, we see a lot of strange stuff. Predictions that don’t line up with common sense. Odds that seem to defy reality. Obviously noncredible market movements. To figure out why, we’ll have to explore the underlying mechanisms that make markets work, and why the typical user of political prediction markets may not behave in the ways we expect. Coming upon an Andre as you turn a corner in a gallery can be a lovely surprise. But for all the smaller controversies it has generated, it has become almost impossible to look down at Andre’s bricks, to tread his floors of metal plates, or gaze at his constructions of cut ash and cedar timbers, without thinking of the death of the

Coming upon an Andre as you turn a corner in a gallery can be a lovely surprise. But for all the smaller controversies it has generated, it has become almost impossible to look down at Andre’s bricks, to tread his floors of metal plates, or gaze at his constructions of cut ash and cedar timbers, without thinking of the death of the  The biggest recent find in classical music was the discovery that in 1940, Sergei Rachmaninoff was privately recorded by the conductor Eugene Ormandy. Seated at Ormandy’s piano, he played through his new Symphonic Dances, which Ormandy would soon premiere with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Singularly, Rachmaninoff never permitted his public performances to be broadcast—so this surreptitious home recording is the best evidence we have of what Rachmaninoff’s legendary pianism sounded like outside the confines of recording studios sucked clean of the oxygen a body of listeners can activate.

The biggest recent find in classical music was the discovery that in 1940, Sergei Rachmaninoff was privately recorded by the conductor Eugene Ormandy. Seated at Ormandy’s piano, he played through his new Symphonic Dances, which Ormandy would soon premiere with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Singularly, Rachmaninoff never permitted his public performances to be broadcast—so this surreptitious home recording is the best evidence we have of what Rachmaninoff’s legendary pianism sounded like outside the confines of recording studios sucked clean of the oxygen a body of listeners can activate. F

F For the past decade, Collinge and his team have studied people in the United Kingdom who in childhood

For the past decade, Collinge and his team have studied people in the United Kingdom who in childhood  The first video portapacks arrived in the 1970s, cameras that skipped the lab and allowed the cameraman to be mobile, but they were so expensive only those who had connections with a TV station could experiment with them. Or if you had a rich aunt who needed to document a wedding, sometimes exorbitant rentals were available. Those with the ties to TV stations became the pioneers of art video. The rest of us painfully wove our laurels out of what could be cadged or granted. The tech, always changing, improved year by year, as did access and the imagery. We were offered new ways to think about color, resolution, and the translation of experience to video. Seeing invention at work as each new video tool appeared – sometimes developed by the artists themselves – was thrilling.

The first video portapacks arrived in the 1970s, cameras that skipped the lab and allowed the cameraman to be mobile, but they were so expensive only those who had connections with a TV station could experiment with them. Or if you had a rich aunt who needed to document a wedding, sometimes exorbitant rentals were available. Those with the ties to TV stations became the pioneers of art video. The rest of us painfully wove our laurels out of what could be cadged or granted. The tech, always changing, improved year by year, as did access and the imagery. We were offered new ways to think about color, resolution, and the translation of experience to video. Seeing invention at work as each new video tool appeared – sometimes developed by the artists themselves – was thrilling.