Category: Archives

An Unnatural Politics and the Madness of the Indian State

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee in The Wire:

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee in The Wire:

There is an anecdote in Salvador Dali’s Diary of a Genius, where he recounts telling three men from Barcelona, nothing that occurs in the world astonishes him. Upon which a well-known watchmaker among them asks Dali, if he saw the sun coming out in the middle of the night, wouldn’t he be astonished? No, said Dali, it wouldn’t bother him the least. The watchmaker confessed, if he witnessed such a thing, he would have thought he had gone mad. To which, Dali replied with witty assurance, “I should think it was the sun that had gone mad.”

The modern counterparts of Dali’s watchmaker believe there is something mad about the student protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). In fact, the madness lies elsewhere.

Muslim students, finding their place as equal subjects under the law shrinking drastically after the CAA was passed by both houses of parliament last week, have reacted sharply. Protests were spearheaded by two Muslim educational institutions, Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University. The logic of the government had reached them. But more significantly perhaps, what reached them was a sense of suffocation.

Since 2014, there has been an unprecedented attack on Muslims in social spaces. It started with the lynchings on rumours of beef eating and transporting cattle. The territorialisation of the Hindu nation had begun with that move.

More here.

Chained to Globalization

Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman in Foreign Affairs:

Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman in Foreign Affairs:

[Thomas] Friedman was right that a globalized world had arrived but wrong about what that world would look like. Instead of liberating governments and businesses, globalization entangled them. As digital networks, financial flows, and supply chains stretched across the globe, states—especially the United States—started treating them as webs in which to trap one another. Today, the U.S. National Security Agency lurks at the heart of the Internet, listening in on all kinds of communications. The U.S. Department of the Treasury uses the international financial system to punish rogue states and errant financial institutions. In service of its trade war with China, Washington has tied down massive firms and entire national economies by targeting vulnerable points in global supply chains. Other countries are in on the game, too: Japan has used its control over key industrial chemicals to hold South Korea’s electronics industry for ransom, and Beijing might eventually be able to infiltrate the world’s 5G communications system through its access to the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei.

Globalization, in short, has proved to be not a force for liberation but a new source of vulnerability, competition, and control; networks have proved to be less paths to freedom than new sets of chains. Governments and societies, however, have come to understand this reality far too late to reverse it. In the past few years, Beijing and Washington have been just the most visible examples of governments recognizing how many dangers come with interdependence and frantically trying to do something about it. But the economies of countries such as China and the United States are too deeply entwined to be separated—or “decoupled”—without causing chaos.

Lisa Robertson’s Bottomless Novel of Authorship and Baudelaire

Jennifer Krasinski at Bookforum:

In the years before a woman becomes a writer, the rooms are never her own, and that can be a very fine thing. Decades before receiving the Baudelairian authorship, when she first moved to Paris as a young woman, Hazel Brown stayed in cheap hotels, admiring the neutrality of spaces designed for everyone and no one: “No judgment, no need, no contract, no seduction: just the free promiscuity of a disrobed mind.” She thereafter sublets teensy, humble apartments, living alongside the unremarkable belongings of people she doesn’t know—an actress (a role-player), a graphologist (a handwriting analyst). She spends her days reading in the park, filling her head with the words of others, of people she also doesn’t know, and picking up boys to kiss and fuck. She is equally enamored of sex and sentences; each, sensual and electrifying, grazes her body, at once possessing it and proving its otherness. She takes menial jobs: one at the summer house of a convalescing widow, for whom she performs all manner of household duties; later, she’s hired to mind the daughter of a wealthy couple, shuttling her from school back to their apartment, where Hazel Brown does the ironing and dusting, playing proxy for the wife and mother who recently returned to work.

In the years before a woman becomes a writer, the rooms are never her own, and that can be a very fine thing. Decades before receiving the Baudelairian authorship, when she first moved to Paris as a young woman, Hazel Brown stayed in cheap hotels, admiring the neutrality of spaces designed for everyone and no one: “No judgment, no need, no contract, no seduction: just the free promiscuity of a disrobed mind.” She thereafter sublets teensy, humble apartments, living alongside the unremarkable belongings of people she doesn’t know—an actress (a role-player), a graphologist (a handwriting analyst). She spends her days reading in the park, filling her head with the words of others, of people she also doesn’t know, and picking up boys to kiss and fuck. She is equally enamored of sex and sentences; each, sensual and electrifying, grazes her body, at once possessing it and proving its otherness. She takes menial jobs: one at the summer house of a convalescing widow, for whom she performs all manner of household duties; later, she’s hired to mind the daughter of a wealthy couple, shuttling her from school back to their apartment, where Hazel Brown does the ironing and dusting, playing proxy for the wife and mother who recently returned to work.

more here.

Life, Death and Revolution in Egypt

William Dalrymple at The Guardian:

Of all the ill-fated revolutions of the Arab spring, none started more optimistically, or ended more disappointingly, than that of Egypt. President Hosni Mubarak, who was overthrown with such rejoicing at the beginning of the revolution in 2011, was perhaps not the worst of the Arab dictators. His rise, on the classless elevator of the Egyptian armed forces, was entirely the result of his competence in the military. Cairo intellectuals disliked his backslapping air-force bonhomie and quickly dubbed him “La vache qui rit”, after the laughing cow on the French processed cheese to whom the president was said to bear a resemblance.

Of all the ill-fated revolutions of the Arab spring, none started more optimistically, or ended more disappointingly, than that of Egypt. President Hosni Mubarak, who was overthrown with such rejoicing at the beginning of the revolution in 2011, was perhaps not the worst of the Arab dictators. His rise, on the classless elevator of the Egyptian armed forces, was entirely the result of his competence in the military. Cairo intellectuals disliked his backslapping air-force bonhomie and quickly dubbed him “La vache qui rit”, after the laughing cow on the French processed cheese to whom the president was said to bear a resemblance.

For two decades Mubarak provided Egypt with a plodding yet stable government, which many compared favourably with the attention-seeking antics of his predecessors Nasser and Sadat. It should not be forgotten that his ministers were corrupt, his police casually and strikingly brutal, and torture in Egyptian prisons was rife. Yet his regime was still better than its counterparts in Syria and Iraq.

more here.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Recycling

Matthew King at The Baffler:

Modern recycling as we know it—the byzantine system of color-coded bins and asterisk-ridden instruction sheets about what is or isn’t “recyclable”—was conceived in a boardroom. The anti-litter campaigns of the 1950s, championed under the slogan of “Keep America Beautiful,” were funded by the producers of that litter, who sought to position recycling as a viable alternative to the sustainable packaging laws that had percolated in nearly two dozen states. In primetime commercials over the decades, American audiences met characters like Susan Spotless and “The Crying Indian” (played by Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti) who urged consumers to lead the charge against debris: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Modern recycling as we know it—the byzantine system of color-coded bins and asterisk-ridden instruction sheets about what is or isn’t “recyclable”—was conceived in a boardroom. The anti-litter campaigns of the 1950s, championed under the slogan of “Keep America Beautiful,” were funded by the producers of that litter, who sought to position recycling as a viable alternative to the sustainable packaging laws that had percolated in nearly two dozen states. In primetime commercials over the decades, American audiences met characters like Susan Spotless and “The Crying Indian” (played by Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti) who urged consumers to lead the charge against debris: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Keep America Beautiful flaunted a fairy tale logic that demanded little from anyone. Landscapes would be rendered pristine as long as responsible citizens placed their garbage in the proper receptacle. Any unwanted items could be magically whisked away somewhere distant and unseen.

more here.

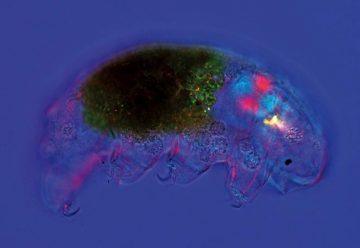

Engineering Life: Synthetic biology and the frontiers of technology

Jonathan Shaw in Harvard Magazine:

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY, or the application of engineering principles to the design of life, presents world-changing prospects. Could components of a living cell function as tiny switches or circuits? How would that allow biomedical engineers to build biological “smart devices”—from sensors deployed inside the body to portable medical kits able to produce vaccines and antibiotics on demand? Could bacterial “factories” replace the fossil-fueled industries that produce plastics, foods, and fertilizers? Will the secrets of living creatures that enter suspended animation during periods of drought and extreme cold be harnessed to keep human victims of trauma alive? And is the genetic information preserved in long-frozen or fossilized extinct species, like woolly mammoths, sufficiently recoverable to help save living species?

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY, or the application of engineering principles to the design of life, presents world-changing prospects. Could components of a living cell function as tiny switches or circuits? How would that allow biomedical engineers to build biological “smart devices”—from sensors deployed inside the body to portable medical kits able to produce vaccines and antibiotics on demand? Could bacterial “factories” replace the fossil-fueled industries that produce plastics, foods, and fertilizers? Will the secrets of living creatures that enter suspended animation during periods of drought and extreme cold be harnessed to keep human victims of trauma alive? And is the genetic information preserved in long-frozen or fossilized extinct species, like woolly mammoths, sufficiently recoverable to help save living species?

These ideas, once the stuff of science fiction, are now the stuff of science. Some aren’t yet functioning realities, but others have launched business applications, whether in medicine (such as hospital gowns that signal exposure to infection) or in land remediation (where bacterial “factories” powered by the sun capture nitrogen from the atmosphere to help plants grow). Someday, engineered forms of life that store carbon may even be one of the solutions to Earth’s climate-change problem.

“Most of biology, historically, has been analyzing how nature works,” says Donald Ingber, director of Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. Systems biology is the culmination of that effort to deconstruct natural processes. Now, with synthetic biology, he points out, scientists “are at the point where we know enough that we can actually engineer artificial and natural biological systems.” Researchers today can build things from biological parts, and even create hybrid systems by linking them to non-living machines. Propelling the science forward are scores of innovations in biological science, with new discoveries coming every month. Among the most important are advances in genetic editing, including improvements in accuracy, and the ability to make hundreds of changes at once.

More here.

Genius and Ink

Aida Edemariam in The Guardian:

Virginia Woolf, aged 23, recently orphaned and still 10 years away from publishing her debut novel, was first commissioned to write reviews for the TLS in 1905. She began, as Francesca Wade points out in her preface to this collection, like any novice – by reviewing anything the editors sent her: guide books, cookery books, poetry, debut novels. Often she was filing a piece a week, reading the book on Sunday, writing – in the anonymous, authoritative TLS first-person plural “we” – up to 1,500 words on Monday, to be printed on Friday. The reviews gave her independence, and they made her a writer.

Virginia Woolf, aged 23, recently orphaned and still 10 years away from publishing her debut novel, was first commissioned to write reviews for the TLS in 1905. She began, as Francesca Wade points out in her preface to this collection, like any novice – by reviewing anything the editors sent her: guide books, cookery books, poetry, debut novels. Often she was filing a piece a week, reading the book on Sunday, writing – in the anonymous, authoritative TLS first-person plural “we” – up to 1,500 words on Monday, to be printed on Friday. The reviews gave her independence, and they made her a writer.

Through these pieces she “learnt a lot of my craft”, she once recalled; “how to compress; how to enliven”, how “to read with a pen & notebook, seriously”. She could not of course have managed it without a childhood of reading (“the great season for reading is the season between the ages of18 and 24”, as she puts it, somewhat archly, in “Hours in a Library”). Also essential was the cultural capital she took for granted as the daughter of leading man of letters Leslie Stephen (and which she recognises as a foundation of Fanny Burney’s work: “all the stimulus that comes from running in and out of rooms where grown-up people are talking about books and music”). She possessed the journalist’s and then the novelist’s gift for detail (the 107 dinner parties Henry James attended in one season, for instance, without being appreciably impressed by any of them), and the humility, at least at first, to understand that she must earn the attention of “busy people catching trains in the mornings” and “tired people coming home in the evening”.

She was working out, too, what being a critic meant. ‘A great critic” – a “Coleridge, above all” – “is the rarest of beings” she believed; what’s more, he wrote of drama and of poetry. The criticism of fiction “is in its infancy”, she wrote. This was an opportunity, but also a challenge – for where, as a young woman, and an autodidact, did she fit in? That gender-ambiguous “we” sometimes feels like a cloak swept about her with too much bravado.

More here.

Saturday Poem

To the Person(s) Who Drowned Beehives

and set others on Fire, Killing 6000,000 Bees

When I was a kid, wild bees swarmed a plum tree

on Dad’s property. From our picture window,

I marveled at the hive pulsing, growing larger. Dad told me,

Don’t throw rocks at the beehive. He didn’t say, Leave

the hive alone. Look at it, but don’t bother the bees.

Dad anticipated me at my worst. I speculated about my ability

to outrun rock-stunned, furious bees. I thought I could,

but didn’t throw a rock. Wary of the righteous sting

of Dad’s meted-out punishments, I didn’t drown the hive,

or set fire to it, either. Dad called a local beekeeper

to give the swarm a new home. I remember Jim Buchan,

helmet-veil shielding his face and neck. In a bee suit,

smoker swaying in one hand like a censer. I remember

his calm, his respect, his devotion akin to love.

In a moment, bees filled our sky, were everywhere.

I remember wonder, and honeycomb oozing amber liquid

made from nectar gathered in Dad’s bloom-crazy yard.

I remember my bee-sweet teeth, satiated for once.

by Andrew Shattuck McBride

from Empty Mirror Books.com

Friday, December 20, 2019

Down through the layers: the paintings of Mark Bradford

Morgan Meis in The Easel:

For at least a decade now there’s been a buzz about Mark Bradford. People call him an exciting painter. Those two words, “exciting” and “painting,” don’t get put together very often, which is understandable. There is something about painting that promotes a reflective attitude. You look at a painting by standing your distance and contemplating. You can like a painting, love a painting, even be moved by a painting. But excitement? Not so much. What is it about Bradford’s paintings that makes them exciting? The answer, I think, is that Bradford has discovered an approach to abstraction that’s genuinely fresh, genuinely new. No one’s done it quite like this before.

For at least a decade now there’s been a buzz about Mark Bradford. People call him an exciting painter. Those two words, “exciting” and “painting,” don’t get put together very often, which is understandable. There is something about painting that promotes a reflective attitude. You look at a painting by standing your distance and contemplating. You can like a painting, love a painting, even be moved by a painting. But excitement? Not so much. What is it about Bradford’s paintings that makes them exciting? The answer, I think, is that Bradford has discovered an approach to abstraction that’s genuinely fresh, genuinely new. No one’s done it quite like this before.

So, let’s get right down to describing what Mark Bradford does when making a painting: He collects stuff. Much of the time, this happens in the city of Los Angeles. Bradford drives around LA, generally close to his neighborhood in South Central, (where he grew up) but ranging wider as the need may be. Born in 1961, he was, beginning as a child, and off and on for years, an assistant in his mother’s hair salon in Leimert Park. After high school, he got himself licensed as a hairdresser so he could work in the shop full time. It was not until Bradford was thirty years old that he entered into any formal art training. He went to CalArts in 1991 and emerged with an MFA in 1997. Twelve years later he picked up a MacArthur “Genius” Award for his paintings and, in 2014, a US Department of State’s Medal of Arts. His paintings currently sell in the two to fifteen million dollar range on the international market. The sticker price is amazing in itself but even more so because his works are physically huge and therefore unwieldy for the collector. Not bad for a late starter.

More here.

Taking Sex Differences in Personality Seriously

Scott Barry Kaufman in Scientific American:

A large number of well done studies have painted a rather consistent picture of sex differences in personality that are strikingly consistent across cultures (see here, here, and here). It turns out that the most pervasive sex differences are seen at the “narrow” level of personality traits, not the “broad” level (see here for a great example of this basic pattern).

A large number of well done studies have painted a rather consistent picture of sex differences in personality that are strikingly consistent across cultures (see here, here, and here). It turns out that the most pervasive sex differences are seen at the “narrow” level of personality traits, not the “broad” level (see here for a great example of this basic pattern).

At the broad level, we have traits such as extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness. But when you look at the specific facets of each of these broad factors, you realize that there are some traits that males score higher on (on average), and some traits that females score higher on (on average), so the differences cancel each other out. This canceling out gives the appearance that sex differences in personality don’t exist when in reality they very much do exist.

For instance, males and females on average don’t differ much on extraversion. However, at the narrow level, you can see that males on average are more assertive (an aspect of extraversion) whereas females on average are more sociable and friendly (another aspect of extraversion). So what does the overall picture look like for males and females on average when going deeper than the broad level of personality?

More here.

The Profligate Love Poems of Walter Benton

Kathleen Rooney at Poetry Magazine:

Benton was massively popular in his heyday. This Is My Beloved came out in 1943; Billboard reported in early 1949 that the book had sold more than 350,000 copies, and it remained continuously in print for decades. Benton’s work appeared in the Yale Review, Esquire, the New Republic, Poetry, and other prestigious outlets, but he’s best remembered today (if at all) for his World War II poetry. The only contemporary review of This Is My Beloved I could track down was in Kirkus Reviews in 1942. It’s a wry, saucy write-up that reads: “High voltage verse, this, in free verse for a sequence of lyrics commemorating a love affair and its termination. Intimate corporeal and physical detail and extravagant praise thereof, in what might mildly be termed erotica. D.H. Lawrence—move over.”

Benton was massively popular in his heyday. This Is My Beloved came out in 1943; Billboard reported in early 1949 that the book had sold more than 350,000 copies, and it remained continuously in print for decades. Benton’s work appeared in the Yale Review, Esquire, the New Republic, Poetry, and other prestigious outlets, but he’s best remembered today (if at all) for his World War II poetry. The only contemporary review of This Is My Beloved I could track down was in Kirkus Reviews in 1942. It’s a wry, saucy write-up that reads: “High voltage verse, this, in free verse for a sequence of lyrics commemorating a love affair and its termination. Intimate corporeal and physical detail and extravagant praise thereof, in what might mildly be termed erotica. D.H. Lawrence—move over.”

Whatever critics’ ambivalence, Benton wrote one of the bestselling poetry collections in America. Why had I never heard of him? Exposure doesn’t equal merit, of course, but these poems had resonated with hundreds of thousands of readers over the years and now struck a chord in me. I wanted to understand why.

more here.

Q&A with Dr. Azra Raza

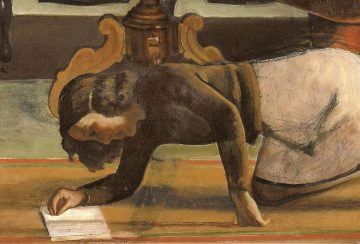

Looking at the Book of Balthus

Johanna Ekström at Cabinet Magazine:

When I was a child, there was a book about the Polish artist Balthus in the small library at our country home. It was dad’s book, big and heavy. The skin between my thumb and index finger stretched taut when I took it down from the shelf. Sometimes I would sit at the table there in the library and page through the book. The table was by a window that looked out on a forest of firs. The light from the window was dim and pale; it seemed to lack strength and direction.

When I was a child, there was a book about the Polish artist Balthus in the small library at our country home. It was dad’s book, big and heavy. The skin between my thumb and index finger stretched taut when I took it down from the shelf. Sometimes I would sit at the table there in the library and page through the book. The table was by a window that looked out on a forest of firs. The light from the window was dim and pale; it seemed to lack strength and direction.

I recognized the color palette in the book from museum visits with my parents. We always made our way to the hall with “the Dutch.” Those soft, melty tones, light filtering through a colored glass or an open window, tender and clarifying, causing skin or milk or the yellow fabric of a skirt to press forward and move the viewer. Balthus’s tranquility was Dutch. Still-life quiet. There was a desire for sleep or absence.

more here.

Translation Of A New York Times Real Estate Article For Those Living Without A Trust Fund

Marco Kaye in McSweeney’s:

When Guy Partnerman and Lady Millionaire purchased a brownstone in the most Brooklyn-themed neighborhood of Brooklyn, there was only one drawback: the home was too beautiful.

When Guy Partnerman and Lady Millionaire purchased a brownstone in the most Brooklyn-themed neighborhood of Brooklyn, there was only one drawback: the home was too beautiful.

“Crown-molded ceilings, natural sunlight, not a trace of ‘Live, Laugh, Love’ decor. To call it a fixer-upper wouldn’t be right, but we had some ideas. That’s who we are. People with ideas and the means to execute them flawlessly,” said Ms. Millionaire, 37, a movement-based flautist.

“We couldn’t just raze the thing in the grand tradition of the heathens we pretend not to be,” added Mr. Partnerman, 69. “There were ordinances.”

Thanks to privilege, the couple moved quickly on an offer, an eye-watering sum that makes you feel karmically flawed. They inspected the home with their clear-frame glasses and unisex workwear. Mr. Partnerman, a commodities trader specializing in shorting pork futures, is a sustainable design buff. He realized he could rip up the floorboards, cabinets, walls, and every historic detail, replacing it with Amazonian timber salvaged from impending wildfires.

More here.

A Figure Model’s (Brief) Guide to Poses through Art History

Larissa Pham at The Paris Review:

A figure drawing session frequently starts with gesture drawings—quick, thirty-second poses, which allow the artists to warm up with looser, broader marks, filling up the page. For quick poses, emphasizing vertical and horizontal lines, one might draw on some early examples of figurative sculpture: Egyptian funerary statues, in standing and seated poses, like this one of Hatshepsut at the Met. The ancient Egyptians believed in life after death; the statues were intended to be images of the body that the immortal soul could return to. As such, they’re made to last forever: sturdy, straight-spined, shoulders and hips in perfect alignment. The funerary and religious statuary of the ancient Egyptians wasn’t dissimilar to that of the Archaic Greeks, whose kouros sculptures depicted beautiful male youths, their backs straight, weight evenly distributed, one foot extended aristocratically as if midstride.

more here.

Friday Poem

Bessie Smith

Homage to the Empress of the Blues

Because there was a man somewhere in a candystripe silk shirt,

gracile and dangerous as a jaguar and because a woman moaned for him

in sixty-watt gloom and mourned him Faithless Love

Twotiming Love Oh Love Oh Careless Aggravating Love,

….. She came out on the stage in yards of pearls, emerging like

….. a favorite scenic view, flashed her golden smile and sang.

Because grey laths began somewhere to show from underneath

torn hurdygurdy lithographs of dollfaced in heaven;

and because there were those who feared alarming fists of snow

on the door and those who feared the riot-squad of statistics,

….. She came out on the stage in ostrich feathers, beaded satin,

….. and shone that smile on us and sang.

by Robert Hayden

from The Norton Anthology

Norton & Company, 2003

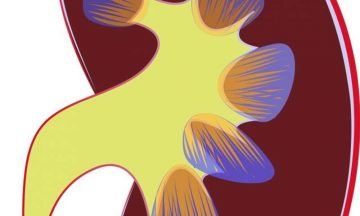

Finding familiar pathways in kidney cancer

From Phys.Org:

p53 is the most famous cancer gene, not least because it’s involved in causing over 50% of all cancers. When a cell loses its p53 gene—when the gene becomes mutated—it unleashes many processes that lead to the uncontrolled cell growth and refusal to die, which are hallmarks of cancer growth. But there are some cancers, like kidney cancer, that that had few p53 mutations. In order to understand whether the inactivation of the p53 pathway might contribute to kidney cancer development, Haifang Yang, Ph.D., a researcher with the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center—Jefferson Health probed kidney cancer’s genes for interactions with p53.

p53 is the most famous cancer gene, not least because it’s involved in causing over 50% of all cancers. When a cell loses its p53 gene—when the gene becomes mutated—it unleashes many processes that lead to the uncontrolled cell growth and refusal to die, which are hallmarks of cancer growth. But there are some cancers, like kidney cancer, that that had few p53 mutations. In order to understand whether the inactivation of the p53 pathway might contribute to kidney cancer development, Haifang Yang, Ph.D., a researcher with the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center—Jefferson Health probed kidney cancer’s genes for interactions with p53.

Emotional Words Such as “Love” Mean Different Things in Different Languages

Diana Kwon in Scientific American:

Humans boast a rich trove of words to express the way we feel. Some are not easily translatable between languages: Germans use “Weltschmerz” to refer to a feeling of melancholy caused by the state of the world. And the indigenous Baining people of Papua New Guinea say “awumbuk” to describe a social hangover that leaves people unmotivated and listless for days after the departure of overnight guests. Other terms seem rather common—“fear,” for example, translates to “takot” in Tagalog and “ótti” in Icelandic. These similarities and differences raise a question: Does the way we experience emotions cross cultural boundaries?

Humans boast a rich trove of words to express the way we feel. Some are not easily translatable between languages: Germans use “Weltschmerz” to refer to a feeling of melancholy caused by the state of the world. And the indigenous Baining people of Papua New Guinea say “awumbuk” to describe a social hangover that leaves people unmotivated and listless for days after the departure of overnight guests. Other terms seem rather common—“fear,” for example, translates to “takot” in Tagalog and “ótti” in Icelandic. These similarities and differences raise a question: Does the way we experience emotions cross cultural boundaries?

Scientists have long questioned whether human emotions share universal roots or vary across cultures. Early evidence suggested that, in the same way that primary colors give rise to all of the other hues, there was a core set of primary emotions from which all other feelings arose. In the 1970s, for instance, researchers reported that people in an isolated cultural group in Papua New Guinea were able to correctly identify emotional expressions in photographed Western faces at rates higher than chance. “This was largely taken as evidence that people around the world could understand emotions in the same way,” says Kristen Lindquist, an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. But more recent studies have challenged this idea. Work from a variety of fields—psychology, neuroscience and anthropology—has provided evidence that the way people express and experience emotions may be greatly influenced by our cultural upbringing. Many of these studies have limitations, however. Most have either looked only at comparisons between two cultures or focused on big, industrialized countries, says Joshua Jackson, a doctoral student in psychology at Chapel Hill. “We haven’t really had the power to test [the universality of emotion] on an appropriate scale.”

More here.

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Inequality and Human Rights

Katharine Young in Inference Review:

In Not Enough, Samuel Moyn addresses a disjunction between the language of human rights and the facts of inequality. Our unequal world, Moyn observes, is one in which the rich have grown ever richer, but the poor have remained poor, or, at best, not quite as poor as they once were. The language of human rights may not have been the cause of economic inequality, he argues, but neither has it done much to prevent it. Moyn, a professor of law and history at Yale University, draws upon a wide range of sources in making his claims: nineteenth-century debates about distributive ethics, eighteenth-century Jacobin texts and treatises, medieval and ancient sources. Moyn also considers more recent events that have long been associated with the history of human rights: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and later efforts to emphasize material equality and social justice in the context of decolonization. These efforts, Moyn believes, were too easily assimilated in welfare states, or outpaced in others. They converted none to the cause.

In Not Enough, Samuel Moyn addresses a disjunction between the language of human rights and the facts of inequality. Our unequal world, Moyn observes, is one in which the rich have grown ever richer, but the poor have remained poor, or, at best, not quite as poor as they once were. The language of human rights may not have been the cause of economic inequality, he argues, but neither has it done much to prevent it. Moyn, a professor of law and history at Yale University, draws upon a wide range of sources in making his claims: nineteenth-century debates about distributive ethics, eighteenth-century Jacobin texts and treatises, medieval and ancient sources. Moyn also considers more recent events that have long been associated with the history of human rights: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and later efforts to emphasize material equality and social justice in the context of decolonization. These efforts, Moyn believes, were too easily assimilated in welfare states, or outpaced in others. They converted none to the cause.

More here.