Michael Robbins at Bookforum:

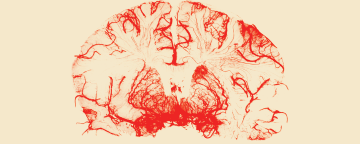

THE HARD PROBLEM, DAVID CHALMERS CALLS IT: Why are the physical processes of the brain “accompanied by an experienced inner life?” How and why is there something it is like to be you and me, in Thomas Nagel’s formulation? I’ve been reading around in the field of consciousness studies for over two decades—Chalmers, Nagel, Daniel Dennett, John Searle, Jerry Fodor, Ned Block, Frank Jackson, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Alva Noë, Susan Blackmore—and the main thing I’ve learned is that no one has the slightest idea. Not that the field lacks for confident pronouncements to the contrary.

THE HARD PROBLEM, DAVID CHALMERS CALLS IT: Why are the physical processes of the brain “accompanied by an experienced inner life?” How and why is there something it is like to be you and me, in Thomas Nagel’s formulation? I’ve been reading around in the field of consciousness studies for over two decades—Chalmers, Nagel, Daniel Dennett, John Searle, Jerry Fodor, Ned Block, Frank Jackson, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Alva Noë, Susan Blackmore—and the main thing I’ve learned is that no one has the slightest idea. Not that the field lacks for confident pronouncements to the contrary.

Briefly stated, the problem is that the world appears to contain two very different kinds of stuff—mind and body, for which Descartes posited two substances, res cogitans and res extensa. The mind is not physical, not extended in space. The body and everything else are made of physical substance and located in space. Substance dualism is out of fashion these days, but some philosophers (including Chalmers) are property dualists, who believe consciousness is an emergent property, a kind of ghostly accompaniment to physical reality.

more here.

G

G By breaking with Capote’s model — by “saying yes to the first person,” as Carrère puts it — he had found his way. When his book, “The Adversary,” was published in 2000, not everybody liked it, neither in France, where Carrère was already well known for his novels and screenplays, nor abroad, where he was largely unknown. But the book became a tremendous success, signaling a new approach to the writing of nonfiction: deeply personal, deeply empathetic, disconcertingly self-revelatory. Carrère spared no one, least of all himself. Each of his books became not only a superb account of its subject but a painful report of the author’s struggle to find a way to write it. His reputation grew with every book, until in an excellent profile of him published in The New York Times Magazine in 2017, Wyatt Mason could state with authority: “If Michel Houellebecq is routinely advanced as France’s greatest living writer of fiction,

By breaking with Capote’s model — by “saying yes to the first person,” as Carrère puts it — he had found his way. When his book, “The Adversary,” was published in 2000, not everybody liked it, neither in France, where Carrère was already well known for his novels and screenplays, nor abroad, where he was largely unknown. But the book became a tremendous success, signaling a new approach to the writing of nonfiction: deeply personal, deeply empathetic, disconcertingly self-revelatory. Carrère spared no one, least of all himself. Each of his books became not only a superb account of its subject but a painful report of the author’s struggle to find a way to write it. His reputation grew with every book, until in an excellent profile of him published in The New York Times Magazine in 2017, Wyatt Mason could state with authority: “If Michel Houellebecq is routinely advanced as France’s greatest living writer of fiction,  In September of this year, pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai announced that they were halting Phase 3 clinical trials of a drug, elenbecestat, aimed at thwarting amyloid-β buildup in Alzheimer’s disease. Although the drug had seemed so promising that the companies elected to test it in two Phase 3 trials simultaneously, preliminary analyses determined that elenbecestat’s risks outweighed its benefits, and the drug shouldn’t be moved to market. The cancellation “amounts to a further step in the unwinding of Biogen’s expensive, painful, and ultimately fruitless investment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drug development,” analyst Geoffrey Porges told

In September of this year, pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai announced that they were halting Phase 3 clinical trials of a drug, elenbecestat, aimed at thwarting amyloid-β buildup in Alzheimer’s disease. Although the drug had seemed so promising that the companies elected to test it in two Phase 3 trials simultaneously, preliminary analyses determined that elenbecestat’s risks outweighed its benefits, and the drug shouldn’t be moved to market. The cancellation “amounts to a further step in the unwinding of Biogen’s expensive, painful, and ultimately fruitless investment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drug development,” analyst Geoffrey Porges told  Occupants of the American meritocracy are accustomed to telling stirring stories about their lives. The standard one is a comforting tale about grit in the face of adversity – overcoming obstacles, honing skills, working hard – which then inevitably affords entry to the Promised Land. Once you have established yourself in the upper reaches of the occupational pyramid, this story of virtue rewarded rolls easily off the tongue. It makes you feel good (I got what I deserved) and it reassures others (the system really works). But you can also tell a different story, which is more about luck than pluck, and whose driving forces are less your own skill and motivation, and more the happy circumstances you emerged from and the accommodating structure you traversed. As an example, here I’ll tell my own story about my career negotiating the hierarchy in the highly stratified system of higher education in the United States. I ended up in a cushy job as a professor at Stanford University. How did I get there? I tell the story both ways: one about pluck, the other about luck. One has the advantage of making me more comfortable. The other has the advantage of being more true.

Occupants of the American meritocracy are accustomed to telling stirring stories about their lives. The standard one is a comforting tale about grit in the face of adversity – overcoming obstacles, honing skills, working hard – which then inevitably affords entry to the Promised Land. Once you have established yourself in the upper reaches of the occupational pyramid, this story of virtue rewarded rolls easily off the tongue. It makes you feel good (I got what I deserved) and it reassures others (the system really works). But you can also tell a different story, which is more about luck than pluck, and whose driving forces are less your own skill and motivation, and more the happy circumstances you emerged from and the accommodating structure you traversed. As an example, here I’ll tell my own story about my career negotiating the hierarchy in the highly stratified system of higher education in the United States. I ended up in a cushy job as a professor at Stanford University. How did I get there? I tell the story both ways: one about pluck, the other about luck. One has the advantage of making me more comfortable. The other has the advantage of being more true. One need not have phobia about science, while finding what has come to be called “scientism” intellectually distasteful. This is a familiar distinction, oft made.

One need not have phobia about science, while finding what has come to be called “scientism” intellectually distasteful. This is a familiar distinction, oft made. “Today’s robots lack feelings,” Man and Damasio write

“Today’s robots lack feelings,” Man and Damasio write  Early this October about 13,000 people descended onto a poplar

Early this October about 13,000 people descended onto a poplar  When Benjamin was released from the Clos St. Joseph internment camp in Nevers in the spring of 1940, he returned to Paris for a brief period before fleeing to Lourdes around June 14, en route to Marseilles. It was during this time that he wrote what would become his final work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” or as it is also translated, “On the Concept of History.”

When Benjamin was released from the Clos St. Joseph internment camp in Nevers in the spring of 1940, he returned to Paris for a brief period before fleeing to Lourdes around June 14, en route to Marseilles. It was during this time that he wrote what would become his final work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” or as it is also translated, “On the Concept of History.” A new idea, Rosenberg writes, emerged toward the end of the Second World War, that classical music could be so inspirational to a nation that it might help win a war. Thus was Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony—its first three movements composed in Leningrad as the city was besieged by the Germans—championed in this country as a symbol of freedom and antifascism. The symphony’s artistic merits were less important than its inherent political value, and a national radio audience, hearing the work for the first time on July 19, 1942, was held in a fevered thrall. With the advent of the Cold War and fears growing about the spread of communism, music was increasingly seen to be “interwoven with the democratic aspirations of the American people.” It was, sometimes in not so subtle ways, weaponized. How else to explain the dispatch of symphony orchestras on diplomatic missions abroad? This exporting of American culture to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, where artistic freedoms were brutally suppressed, was both a means of promoting democracy and a master stroke of propaganda. And when the pianist Van Cliburn won first prize at the first Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958, he was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. His triumph went far beyond the realm of art; Cliburn, the tall, handsome Texan who had melted Russian hearts with Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, had scored one for the West.

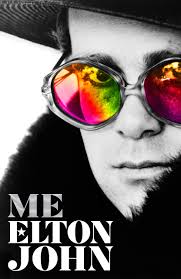

A new idea, Rosenberg writes, emerged toward the end of the Second World War, that classical music could be so inspirational to a nation that it might help win a war. Thus was Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony—its first three movements composed in Leningrad as the city was besieged by the Germans—championed in this country as a symbol of freedom and antifascism. The symphony’s artistic merits were less important than its inherent political value, and a national radio audience, hearing the work for the first time on July 19, 1942, was held in a fevered thrall. With the advent of the Cold War and fears growing about the spread of communism, music was increasingly seen to be “interwoven with the democratic aspirations of the American people.” It was, sometimes in not so subtle ways, weaponized. How else to explain the dispatch of symphony orchestras on diplomatic missions abroad? This exporting of American culture to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, where artistic freedoms were brutally suppressed, was both a means of promoting democracy and a master stroke of propaganda. And when the pianist Van Cliburn won first prize at the first Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958, he was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. His triumph went far beyond the realm of art; Cliburn, the tall, handsome Texan who had melted Russian hearts with Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, had scored one for the West. Elton makes

Elton makes Reciting Jewish achievements and Judaism’s contribution to civilization in order to fight anti-Semitic propaganda is a well-established genre that flourished in 19th-century Europe. After reaching the United States in the first part of the 20th century, it arguably culminated in the 1960s with the writings of popular authors like

Reciting Jewish achievements and Judaism’s contribution to civilization in order to fight anti-Semitic propaganda is a well-established genre that flourished in 19th-century Europe. After reaching the United States in the first part of the 20th century, it arguably culminated in the 1960s with the writings of popular authors like  A cave-wall depiction of a pig and buffalo hunt is the world’s oldest recorded story, claim archaeologists who discovered the work on the Indonesian island Sulawesi. The scientists say the scene is more than 44,000 years old.

A cave-wall depiction of a pig and buffalo hunt is the world’s oldest recorded story, claim archaeologists who discovered the work on the Indonesian island Sulawesi. The scientists say the scene is more than 44,000 years old. Cusk is best known in the US for her Outline trilogy, a series of slim, challenging novels that follow Faye, a cryptic, intelligent narrator whose life and perspective seem to mirror Cusk’s own. Coventry gathers essays written before, during, and after the period in which Cusk was at work on the trilogy. Almost all have appeared elsewhere, but collecting them gives readers a chance to draw a link between Cusk the memoirist (there are essays on marriage and divorce) and Cusk the novelist (there are short pieces on writers like Edith Wharton, D. H. Lawrence, and Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as longer meditations on literary value).

Cusk is best known in the US for her Outline trilogy, a series of slim, challenging novels that follow Faye, a cryptic, intelligent narrator whose life and perspective seem to mirror Cusk’s own. Coventry gathers essays written before, during, and after the period in which Cusk was at work on the trilogy. Almost all have appeared elsewhere, but collecting them gives readers a chance to draw a link between Cusk the memoirist (there are essays on marriage and divorce) and Cusk the novelist (there are short pieces on writers like Edith Wharton, D. H. Lawrence, and Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as longer meditations on literary value). In 2009, discouraged by the failed climate talks in Copenhagen, Chris told me he believed it might already be too late to stop catastrophic climate change. “The old world,” he said, “is gone.” It was a torch-passing moment. Chris was paralyzed by a conviction in his own failure. He had become complacent, he felt, and addicted to television: the sort of person he used to despise. But I was just beginning my own journey into environmental despair. I was full of guilt and anxiety and anger and fear about a future filled with loss and death. I began to draw my own elliptical lines through the ethics of the climate crisis. I turned off the heat in my house, even during the bitter Utah winters. I was late everywhere, determined to take a bus to another bus to a train. I obsessed over plastic bags and Styrofoam plates, and insisted on bringing my own plate to a local sandwich shop. I carried my garbage around for a week and roped my friends into doing so, too, each of us hauling a stinking reminder of our consumption from class to class, clearing rooms as we went. I joined a direct action climate justice group; I planned blockades of city streets and got arrested. I joined with Utah Valley farmers to organize against urban sprawl.

In 2009, discouraged by the failed climate talks in Copenhagen, Chris told me he believed it might already be too late to stop catastrophic climate change. “The old world,” he said, “is gone.” It was a torch-passing moment. Chris was paralyzed by a conviction in his own failure. He had become complacent, he felt, and addicted to television: the sort of person he used to despise. But I was just beginning my own journey into environmental despair. I was full of guilt and anxiety and anger and fear about a future filled with loss and death. I began to draw my own elliptical lines through the ethics of the climate crisis. I turned off the heat in my house, even during the bitter Utah winters. I was late everywhere, determined to take a bus to another bus to a train. I obsessed over plastic bags and Styrofoam plates, and insisted on bringing my own plate to a local sandwich shop. I carried my garbage around for a week and roped my friends into doing so, too, each of us hauling a stinking reminder of our consumption from class to class, clearing rooms as we went. I joined a direct action climate justice group; I planned blockades of city streets and got arrested. I joined with Utah Valley farmers to organize against urban sprawl.