Category: Archives

Liberalism at Large: The World according to the Economist

William Keegan at Literary Review:

As the title indicates, this is a book about liberalism and The Economist’s propagation of it. But as the great Professor Joad would have said, ‘It all depends what you mean by liberalism.’ These days there is much talk of the differences between political liberalism, economic liberalism and social liberalism. In the 19th century, when The Economist was establishing its reputation, its commitment to free trade and capitalism was such that, with regard to the humanitarian 1844 Factory Act, it could opine: ‘the more it is investigated, the more we are compelled to acknowledge that in any interference with industry and capital, the law is powerful only for evil, but utterly powerless for good.’

As the title indicates, this is a book about liberalism and The Economist’s propagation of it. But as the great Professor Joad would have said, ‘It all depends what you mean by liberalism.’ These days there is much talk of the differences between political liberalism, economic liberalism and social liberalism. In the 19th century, when The Economist was establishing its reputation, its commitment to free trade and capitalism was such that, with regard to the humanitarian 1844 Factory Act, it could opine: ‘the more it is investigated, the more we are compelled to acknowledge that in any interference with industry and capital, the law is powerful only for evil, but utterly powerless for good.’

Zevin points out that, from the Crimean War to the present day, The Economist has championed ‘liberal imperialism’, to the point where one of its journalists felt able to come out in a farewell speech with the crack that, in all his time there, The Economist ‘never saw a war it didn’t like’.

more here.

On The Curiously Self-Tortured Legacy of Post-Grunge Music

Eli Zeger at The Baffler:

Godsmack is part of an aggressive, no-cowards-allowed milieu of hard rock known as “post-grunge” (or pejoratively “butt rock”), which was at its most lucrative during the late 1990s and throughout the aughts, when it dominated both the rock and pop charts. Obscuring the stylistic boundaries between neighboring genres—country, grunge, and the genre which grunge supposedly killed, hair metal—post-grunge is characterized by its dragging tempos, down-tuned chord progressions, sporadic twanginess, and overly passionate vocals. If you took an eighties power ballad’s major key and turned it minor, you’d have a post-grunge song more or less. Even today, as its pop appeal has vanished, it remains viable in the realm of mainstream rock, selling out amphitheaters and filling up the playlists on “Alt Nation”-type stations. It soundtracks WWE pay-per-views; it’s what plays over the loudspeakers in Six Flags food courts.

Godsmack is part of an aggressive, no-cowards-allowed milieu of hard rock known as “post-grunge” (or pejoratively “butt rock”), which was at its most lucrative during the late 1990s and throughout the aughts, when it dominated both the rock and pop charts. Obscuring the stylistic boundaries between neighboring genres—country, grunge, and the genre which grunge supposedly killed, hair metal—post-grunge is characterized by its dragging tempos, down-tuned chord progressions, sporadic twanginess, and overly passionate vocals. If you took an eighties power ballad’s major key and turned it minor, you’d have a post-grunge song more or less. Even today, as its pop appeal has vanished, it remains viable in the realm of mainstream rock, selling out amphitheaters and filling up the playlists on “Alt Nation”-type stations. It soundtracks WWE pay-per-views; it’s what plays over the loudspeakers in Six Flags food courts.

more here.

Edna O’Brien: “Some Men Like Fairly Trivial Women”

Kate Mossman at The New Statesman:

It is unusual to find a writer of 88 embarking on a dramatic change of style and taking pains to justify it, but O’Brien still cares what people think. The week we met, she’d won the David Cohen Prize for Literature, a major recognition of a lifetime’s work which has, for other winners, been followed by a Nobel Prize. But she is still stung by a New Yorker profile from October in which, over the course of 10,000 words, the staff writer Ian Parker took the decision to put under the microscope the colourful, heightened way she has told her life story. O’Brien remembered a preacher denouncing the provocative (some said “filthy”) The Country Girls in the pulpit of the church near her home in Tuamgraney, then burning it: Parker said no one in the village recalled the same. And her relationship with her mother may not have been as hostile as she’s made out, he suggested – Lena O’Brien speaks affectionately in much of their correspondence…

It is unusual to find a writer of 88 embarking on a dramatic change of style and taking pains to justify it, but O’Brien still cares what people think. The week we met, she’d won the David Cohen Prize for Literature, a major recognition of a lifetime’s work which has, for other winners, been followed by a Nobel Prize. But she is still stung by a New Yorker profile from October in which, over the course of 10,000 words, the staff writer Ian Parker took the decision to put under the microscope the colourful, heightened way she has told her life story. O’Brien remembered a preacher denouncing the provocative (some said “filthy”) The Country Girls in the pulpit of the church near her home in Tuamgraney, then burning it: Parker said no one in the village recalled the same. And her relationship with her mother may not have been as hostile as she’s made out, he suggested – Lena O’Brien speaks affectionately in much of their correspondence…

more here.

How Hallmark Took Over Cable Television

Sarah Larson in The New Yorker:

This year, Hallmark made headlines when it announced that it would produce two holiday movies with Hanukkah themes. In both, however, Christmas is the star. In “Holiday Date,” Brooke (Brittany Bristow) brings an actor, Joel (Matt Cohen), to Whispering Pines, her home town, for the holidays, to pose as her boyfriend—a common phenomenon on Hallmark, and perhaps less so in real life. One afternoon in September, I visited the set, in a house outside Vancouver. The downstairs was festooned with pine sconces, ornaments, and bows. “Tree on the move!” a crew member said. “I’ve never done Hallmark,” Cohen told me. For a decade, he’d played scary roles, including Lucifer, on shows like “Supernatural.” “I committed to the dark side and it paid the bills,” he said. “But this is who I really am. I’m a goofball.”

This year, Hallmark made headlines when it announced that it would produce two holiday movies with Hanukkah themes. In both, however, Christmas is the star. In “Holiday Date,” Brooke (Brittany Bristow) brings an actor, Joel (Matt Cohen), to Whispering Pines, her home town, for the holidays, to pose as her boyfriend—a common phenomenon on Hallmark, and perhaps less so in real life. One afternoon in September, I visited the set, in a house outside Vancouver. The downstairs was festooned with pine sconces, ornaments, and bows. “Tree on the move!” a crew member said. “I’ve never done Hallmark,” Cohen told me. For a decade, he’d played scary roles, including Lucifer, on shows like “Supernatural.” “I committed to the dark side and it paid the bills,” he said. “But this is who I really am. I’m a goofball.”

As “Holiday Date” unfolds, it’s revealed that Joel doesn’t know how to decorate a tree, or hang Christmas lights: he’s Jewish. The family is “surprised but unfazed,” Bristow explained. They incorporate latkes and a menorah into their festivities and teach Joel to deck the halls. “I’ve never celebrated Christmas, but I always wanted to,” he says. In the movie’s trailer, “Silent Night” plays in the background.

That afternoon, I watched as a scene was filmed in which Joel, handsome in a Santa-red sweater, helps Brooke’s young niece, Tessa (Ava Grace Cooper), rehearse for a Christmas pageant. On the monitor, I could see three Christmas trees in the frame. Tessa’s self-absorbed parents, played by the recurring Hallmark bro Peter Benson and the Hallmark villain Anna Van Hooft, walked by, looking at their phones, and opened the front door, obscuring a tree but introducing a wreath. The living room was a riot of Yuletide splendor: trees and garlands. A fire roared in the fireplace, and a row of Christmas stockings hung on the mantel. Above them, a string of blue-and-white letters spelled out “happy hanukkah.” Tessa’s pageant line was about family togetherness: “ ’Cause that’s what Christmas is all about.” Cohen beamed. “Perfect,” he said.

More here.

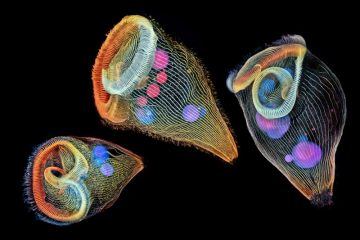

The best science images of the year: 2019 in pictures

Gaind and Callaway in Nature:

2019 will be remembered as the year humanity captured the first-ever image of a black hole. The year also brought fresh views of some of Earth’s smallest living creatures and ominous signs of its changing climate. Here are the most striking shots from science and the natural world that caught the attention of Nature’s news team.

2019 will be remembered as the year humanity captured the first-ever image of a black hole. The year also brought fresh views of some of Earth’s smallest living creatures and ominous signs of its changing climate. Here are the most striking shots from science and the natural world that caught the attention of Nature’s news team.

Tiny trumpets

Stentors — or trumpet animalcules — are a group of single-celled freshwater protozoa. This image won second prize in the 2019 Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition, and was captured at 40 times magnification by researcher Igor Siwanowicz at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia.

More here.

Sunday, December 15, 2019

Living Mirrors: Infinity, Unity, and Life in Leibniz’s Philosophy

Justin E. H. Smith in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

There are several billion microorganisms in a typical teaspoon of soil: not an infinite number, but more than any finite mind could hope to count one by one. Leibniz did not know the precise nature of soil microbes, nor did he have any empirical proof of their existence, but he was convinced that they, or something like them, must exist, and this for deep philosophical reasons. Whatever there is in the world must be underlain by real soul-like unities or centers of action and perception, analogous to whatever it is we are referring to when we speak of “me”. But any such center of action must be outfitted with a body, and this body must be such that no amount of decomposition or removal of parts could ever take the being in question out of existence. Thus there is nothing in the physical world but what Leibniz called “organic bodies” or “natural machines”, that is to say infinitely complex mechanical bodies. Considered together with the active, perceiving unities that underlie them, these organic bodies are best described as “corporeal substances”, of which animals and plants are the varieties we here on the surface of the earth know best. Everything is alive, in short.

There are several billion microorganisms in a typical teaspoon of soil: not an infinite number, but more than any finite mind could hope to count one by one. Leibniz did not know the precise nature of soil microbes, nor did he have any empirical proof of their existence, but he was convinced that they, or something like them, must exist, and this for deep philosophical reasons. Whatever there is in the world must be underlain by real soul-like unities or centers of action and perception, analogous to whatever it is we are referring to when we speak of “me”. But any such center of action must be outfitted with a body, and this body must be such that no amount of decomposition or removal of parts could ever take the being in question out of existence. Thus there is nothing in the physical world but what Leibniz called “organic bodies” or “natural machines”, that is to say infinitely complex mechanical bodies. Considered together with the active, perceiving unities that underlie them, these organic bodies are best described as “corporeal substances”, of which animals and plants are the varieties we here on the surface of the earth know best. Everything is alive, in short.

Leibniz got quite a bit right, though he was wrong about some of the details.

More here.

Revisiting Nuclear Close Calls Since 1945

Bruno Tertrais at the website of La Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique:

Why have nuclear weapons not been used since 1945? The more time passes, the more the question becomes relevant and even puzzling for pessimists. Most strategists of the 1960s would be stunned to hear that as of 2017, there still has yet to be another nuclear use in anger. The prospects of a “nuclear weapons ban” or recurring proposals for “de-alerting”—instituting changes that can lengthen the time required to actually use the weapons—make the question even more relevant. Has mankind really stood “on the brink” several times since Nagasaki, and have we avoided nuclear catastrophe mostly because of pure “luck”? Recent books, articles, and reports, as well as two wide-audience documentaries, say yes.

Why have nuclear weapons not been used since 1945? The more time passes, the more the question becomes relevant and even puzzling for pessimists. Most strategists of the 1960s would be stunned to hear that as of 2017, there still has yet to be another nuclear use in anger. The prospects of a “nuclear weapons ban” or recurring proposals for “de-alerting”—instituting changes that can lengthen the time required to actually use the weapons—make the question even more relevant. Has mankind really stood “on the brink” several times since Nagasaki, and have we avoided nuclear catastrophe mostly because of pure “luck”? Recent books, articles, and reports, as well as two wide-audience documentaries, say yes.

This is not the case. The absence of any deliberate nuclear explosion (except for testing) since 1945 can simply be explained by human prudence and the efficiency of mechanisms devoted to the guardianship of nuclear weapons. Banning nuclear weapons may or may not be a good idea. But it should not be based on the myth of an inherently and permanently high risk of nuclear use.

The analysis that follows covers the deliberate use of nuclear weapons by a legitimate authority, either by error (“false alarm”) or not (“nuclear crisis”). It does not cover the risk of an accidental nuclear explosion, an unauthorized launch, or a terrorist act.3 It covers 37 different known episodes, including 25 alleged nuclear crises and twelve technical incidents, which have been mentioned in the literature to one degree or another as potentially dangerous.

More here.

The mafia is language and symbols

Roberto Saviano in the New York Review of Books:

People think the mafia is first and foremost violence, hit men, threats, extortion, and drug trafficking. But before all else, the mafia is language and symbols. Who doesn’t recall the opening scene of The Godfather, when Vito Corleone extends his hand to Bonasera, the Italian who has come to ask him a “favor,” and who reverently kisses the boss’s hand to ingratiate himself?

Such customs are not obsolete. In June 2017 Giuseppe “the Goat” Giorgi, a boss of the ’Ndrangheta (the Calabrian mafia) and one of Italy’s most dangerous criminals, was arrested. He had gone into hiding twenty-three years earlier, after being convicted of international drug trafficking and sentenced to twenty-eight years and nine months in prison. He was found above the fireplace of his family’s house, in a concealed space that opened by moving a stone in the floor, where he could hide in the event of searches while passing his fugitive days in the comfort of home. As the boss left the building under police escort, fellow villagers paid him tribute, one not only shaking his hand but kissing it.

Although hand-kissing is best known as a gallant way of greeting a lady, to kiss the knuckles of a man is a familiar gesture to anyone who, like me, grew up in southern Italy.

More here.

Gravity-Defying Photos of Dogs Catching Frisbees

More here.

What’s next for psychology’s embattled field of social priming

Tom Chivers in Nature:

Three years ago, a team of psychologists challenged 180 students with a spatial puzzle. The students could ask for a hint if they got stuck. But before the test, the researchers introduced some subtle interventions to see whether these would have any effect. The psychologists split the volunteers into three groups, each of which had to unscramble some words before doing the puzzle. One group was the control, another sat next to a pile of play money and the third was shown scrambled sentences that contained words relating to money. The study, published this June1, was a careful repeat of a widely cited 2006 experiment2. The original had found that merely giving students subtle reminders of money made them work harder: in this case, they spent longer on the puzzle before asking for help. That work was one among scores of laboratory studies which argued that tiny subconscious cues can have drastic effects on our behaviour. Known by the loosely defined terms ‘social priming’ or ‘behavioural priming’, these studies include reports that people primed with ‘money’ are more selfish2; that those primed with words related to professors do better on quizzes3; and even that people exposed to something that literally smells fishy are more likely to be suspicious of others4. The most recent replication effort1, however, led by psychologist Doug Rohrer at the University of South Florida in Tampa, found that students primed with ‘money’ behave no differently on the puzzle task from the controls.

Three years ago, a team of psychologists challenged 180 students with a spatial puzzle. The students could ask for a hint if they got stuck. But before the test, the researchers introduced some subtle interventions to see whether these would have any effect. The psychologists split the volunteers into three groups, each of which had to unscramble some words before doing the puzzle. One group was the control, another sat next to a pile of play money and the third was shown scrambled sentences that contained words relating to money. The study, published this June1, was a careful repeat of a widely cited 2006 experiment2. The original had found that merely giving students subtle reminders of money made them work harder: in this case, they spent longer on the puzzle before asking for help. That work was one among scores of laboratory studies which argued that tiny subconscious cues can have drastic effects on our behaviour. Known by the loosely defined terms ‘social priming’ or ‘behavioural priming’, these studies include reports that people primed with ‘money’ are more selfish2; that those primed with words related to professors do better on quizzes3; and even that people exposed to something that literally smells fishy are more likely to be suspicious of others4. The most recent replication effort1, however, led by psychologist Doug Rohrer at the University of South Florida in Tampa, found that students primed with ‘money’ behave no differently on the puzzle task from the controls.

It is one of dozens of failures to verify earlier social-priming findings. Many researchers say they now see social priming not so much as a way to sway people’s unconscious behaviour, but as an object lesson in how shaky statistical methods fooled scientists into publishing irreproducible results. This is not the only area of research to be dented by science’s ‘replication crisis’. Failed replication attempts have cast doubt on findings in areas from cancer biology to economics. But so many findings in social priming have been disputed that some say the field is close to being entirely discredited.

More here.

Juice Wrld (1998 – 2019)

Caroll Spinney (1933 – 2019)

Marie Fredriksson (1958 – 2019)

A design for death: meeting the bad boy of the euthanasia movement

Mark Smith in 1843 Magazine:

It’s a sunny autumn morning in the Jordaan, Amsterdam’s chocolate-boxiest district. Over tea in a modishly renovated maisonette, a voluble Australian 72 year-0ld wearing round glasses and fashionable denim is regaling me with his new-year plans, which involve “an elegant gas chamber” stationed at a secret location in Switzerland and “a happily dead body”. My host’s name is Philip Nitschke and he’s invented a machine called Sarco. Short for sarcophagus, the slick, spaceship-like pod has a seat for one passenger en-route to the afterlife. It uses nitrogen to enact a pain-free, peaceful death from inert-gas asphyxiation at the touch of a button. With the help of his wife and colleague, the writer and lawyer Dr Fiona Stewart, Nitschke is ushering the death-on-demand movement towards a dramatic new milestone – and their enthusiasm is palpable.

It’s a sunny autumn morning in the Jordaan, Amsterdam’s chocolate-boxiest district. Over tea in a modishly renovated maisonette, a voluble Australian 72 year-0ld wearing round glasses and fashionable denim is regaling me with his new-year plans, which involve “an elegant gas chamber” stationed at a secret location in Switzerland and “a happily dead body”. My host’s name is Philip Nitschke and he’s invented a machine called Sarco. Short for sarcophagus, the slick, spaceship-like pod has a seat for one passenger en-route to the afterlife. It uses nitrogen to enact a pain-free, peaceful death from inert-gas asphyxiation at the touch of a button. With the help of his wife and colleague, the writer and lawyer Dr Fiona Stewart, Nitschke is ushering the death-on-demand movement towards a dramatic new milestone – and their enthusiasm is palpable.

“We’ve got a number of people lined up already, actually,” says Nitschke, whose unique CV (and previous occupation as a registered physician) has earned him the nickname “Dr Death”. The front-runner in the one-way journey to Switzerland is a New Zealander whom Nitschke has known for years. She’s not terminally ill, but is becoming increasingly disabled by macular degeneration – something she finds intolerable after a lifetime of reading for pleasure. “She’s also got an ideological, philosophical supportive commitment to the idea,” explains Nitschke. “She’s coming from a long way because she likes the concept and she sees it as the future.”

Whether that future is utopian or dystopian depends on your perspective. Nitschke has twice been nominated for Australian of the Year for his work with Exit International, the “end-of-life choices information and advocacy organisation” he founded in 1997; activities include the publication of The Peaceful Pill, a continuously updated directory of information on how to end it all. But over the past two decades, members of the medical, psychiatric and even the pro-voluntary euthanasia communities have come to reject his brand of increasingly strident – some say extreme – advocacy for what he terms “rational suicide”: an individual’s inalienable right to die in a manner of their choosing. His one time ally, the former UN medical director Michael Irwin, has branded him “totally irresponsible” for telling people how to obtain drugs that could help them end their own lives. And in August 2019 the grieving daughter of a man who took his life after contact with Exit International denounced Nitschke, saying “the information you put out kills people who are not in a rational state of mind to make that decision.”

More here.

Sunday Poem

Windy Evening

This old world needs propping up

When it gets this cold and windy.

The cleverly painted sets,

Oh, they’re shaking badly!

They’re about to come down.

There’ll be nothing but infinite space.

The silence supreme. Almighty silence.

Egyptian sky. Stars like torches

Of grave robbers entering the crypts of kings.

Even the wind pausing, waiting to see.

Better grab hold of that tree, Lucille.

Its shape crazed, terror-stricken.

I’ll hold on to the barn.

The chickens in it are restless.

Smart chickens, rickety world.

by Charles Simic

from A Wedding in Hell

Harcourt, 1994

Saturday, December 14, 2019

Selling Keynesianism

Robert Manduca in Boston Review:

Robert Manduca in Boston Review:

“Let’s bring our editorial microscope into focus on a very significant phenomenon,” the video begins. “The middle-income consumer.”

As a middle-aged white man comes into view, pushing a wheelbarrow full of recent purchases, the voiceover chronicles his recent exploits. “He has fed new demands into the production apparatus of industry, accounting for the housing boom, appliance sales, the rush for prepared foods.” Altogether, we hear, “the zoom in the American market after the war, the unprecedented volume of goods of all kinds, gobbled up by an insatiable tide of buyers, was largely the work of this middle-income man.”

After decades of praise heaped on “job creators,” viewers today may find it disorienting to see the consumer—and a middle-income one at that—cast as the hero of the economy, instead of the investor or the entrepreneur. Yet Fortune, which produced the video in 1956, was hardly an outlier. In the mid-twentieth century, advertising, popular press, and television bombarded Americans with the message that national prosperity depended on their personal spending. As LIFE proclaimed in 1947, “Family Status Must Improve: It Should Buy More For Itself to Better the Living of Others.” Bride likewise told its readers that when they bought new appliances, “you are helping to build greater security for the industries of this country.”

This messaging was not simply an invention of clever marketers; it had behind it the full force of the best-regarded economic theory of the time, the one elaborated in John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

More here.

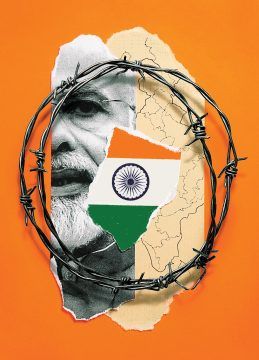

Blood and Soil in Narendra Modi’s India

Dexter Filkins in The New Yorker:

Dexter Filkins in The New Yorker:

In August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to.

Other coverage on Republic TV showed people dancing ecstatically, along with the words “Jubilant Indians celebrate Modi’s Kashmir masterstroke.” A week earlier, Modi’s government had announced that it was suspending Article 370 of the constitution, which grants autonomy to Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state. The provision, written to help preserve the state’s religious and ethnic identity, largely prohibits members of India’s Hindu majority from settling there. Modi, who rose to power trailed by allegations of encouraging anti-Muslim bigotry, said that the decision would help Kashmiris, by spurring development and discouraging a long-standing guerrilla insurgency. To insure a smooth reception, Modi had flooded Kashmir with troops and detained hundreds of prominent Muslims—a move that Republic TV described by saying that “the leaders who would have created trouble” had been placed in “government guesthouses.”

More here.

Afloat with Static

Jenny Turner in the LRB:

Jenny Turner in the LRB:

As a child, Debbie Harry was always searching for ‘the perfect taste’. She couldn’t describe it, but knew she’d know it if she found it. ‘Sometimes, I got a hint of it in peanut butter. Other times … when I drank milk. It was maddening because I was driven to have it.’ She never ate anything, she writes, without wondering if she was at last about to get ‘the flavour of complete satisfaction’.

She grew up and the search was mostly forgotten, though she struggled in secret with bingeing and with worries about getting fat. She’s always been open about the heroin she’s done, over the years, and about how much she enjoyed it: ‘It was so delicious and delightful. For those times when I wanted to blank out parts of my life or when I was dealing with some depression, there was nothing better than heroin. Nothing.’ Now she’s in her seventies, she has ‘a protein and vitamin powder’ that she mixes with coconut water and that tastes ‘satisfyingly familiar’. She blends one up most days. With a careless flip of that flossy halo, the perfect insouciance of her perfect little slotted snarl, she makes the ‘ghostly’ link:

I know that my birth mother kept me for three months. I reason that during this time she breast-fed me and this was the perfect taste. My birth mother kept me and fed me for as long as she could, then she sent me out into the world of choices. The world of flavours. The world. Now, finally, thanks to my maturing, my searching, and my magical shake, I have regained the ability to feel full, to feel hunger, and to enjoy filling up and ending the hunger. True satiation. It seems so simple. Probably as simple as infinity and the universe.

More here.

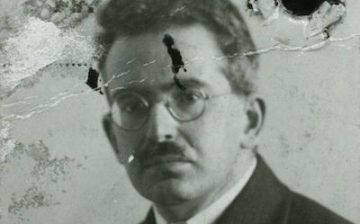

Walter Benjamin’s Last Work

Samantha Rose Hill in the LA Review of Books:

Samantha Rose Hill in the LA Review of Books:

WHEN HANNAH ARENDT escaped the Gurs internment camp in the middle of June 1940, she did not go to Marseilles to find her husband Heinrich Blücher — she went to Lourdes to find Walter Benjamin. For nearly two weeks they played chess from morning to night, talked, and read whatever papers they could find.

Arendt and Benjamin met in exile in Paris in 1933 through her first husband, Günther Anders, who was a distant cousin of Benjamin’s. They would frequent a café on the rue Soufflot to talk politics and philosophy with Bertolt Brecht and Arnold Zweig. And while Arendt’s marriage to Anders didn’t last, her friendship with Benjamin grew and flourished during the war years.

Arendt hesitated leaving Benjamin in Lourdes. She knew he was in a wobbly state of mind, anxious about the future, talking about suicide. Benjamin feared being interned again, and he had difficulty imagining life in the United States. Arendt wrote to Gershom Scholem that the “war immediately terrified him beyond all measure” and “[h]is horror at America was indescribable.” His strained relationship with Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer at the Institute for Social Research (also known as the Frankfurt School) left him in a state of financial precarity. The tenuous flow of correspondence conducted through networks of friends and letters (when they arrived) complicated matters more, leaving one dependent upon time itself. Benjamin, already an anxious man, stopped going out and “was living in constant panic.”

More here.