Sam Dresser in aeon:

At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation?

At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation?

The legendary version of the Buddha’s life states that the Siddhattha Gotama was born as a prince of the Sakya tribe, and raised in the town of Kapilavatthu, several centuries before the Christian era. Living in luxurious seclusion, Siddhattha remained unaware of the difficulties of life, until a visit beyond the palace walls revealed four shocking sights: a sick man, an old man, a dead man and a holy man. The existential crisis this sparked led Siddhattha to renounce the world, in order to seek a spiritual solution to life. After six years of trying out various practices, including extreme asceticism, at the age of 35 Siddhattha attained spiritual realisation. Henceforth known as the ‘Buddha’ – which simply means ‘awakened’ – Siddhattha spent the rest of his life travelling around northern India and establishing a new religious order. He died at the age of 80.

Only the bare details of this account stand up to historical scrutiny. According to contemporary academic opinion, the Buddha lived in the 5th century BCE (c480-400 BCE). But the failure to identify Kapilavatthu implies that he was not a prince who lived in a grand palace. The most likely sites are the Nepalese site of Tilaurakot, an old market town about 10 km north of the Indian border, and the Indian district of Piprahwa, to the south of Tilaurakot and just over the Indian border. But the brick remains at both places are a few centuries later than the Buddha, which at least agrees with the oldest literary sources: according to the Pali canon – the only complete collection of Buddhist literature from ancient India – the Buddha’s world generally lacked bricks, and Kapilavatthu’s only building of note was a tribal ‘meeting hall’ (santhāgāra), an open-sided, thatched hut (sālā).

More here.

Welcome to the second annual Mindscape Holiday Message! No substantive content or deep ideas, just me talking a bit about the state of the podcast and what’s on my mind. Since the big event for me in 2019 was the publication of

Welcome to the second annual Mindscape Holiday Message! No substantive content or deep ideas, just me talking a bit about the state of the podcast and what’s on my mind. Since the big event for me in 2019 was the publication of I

I  When has a voice been this intimate, and versatile? Affectionate, far-reaching, self-aware, and also severe, dismissive of fools?

When has a voice been this intimate, and versatile? Affectionate, far-reaching, self-aware, and also severe, dismissive of fools? Kim Stanley Robinson is, uncharacteristically, at a loss. As a science fiction writer, he is famed for dreaming up utopian futures. But when we meet for lunch in his Californian hometown, at times he struggles to maintain his cool.

Kim Stanley Robinson is, uncharacteristically, at a loss. As a science fiction writer, he is famed for dreaming up utopian futures. But when we meet for lunch in his Californian hometown, at times he struggles to maintain his cool. The quest for a fountain of youth is many centuries old and marred by many false starts and unfulfilled promises. But modern medical science is now gradually closing in on what might realistically enable people to live longer, healthier lives — if they are willing to sacrifice some popular hedonistic pleasures. Specialists in the biology of aging have identified a rarely recognized yet universal condition that is a major contributor to a wide range of common health-robbing ailments, from heart disease, diabetes and cancer to arthritis, depression and Alzheimer’s disease. That condition is chronic inflammation, a kind of low-grade irritant that can undermine the well-being of virtually every bodily system.

The quest for a fountain of youth is many centuries old and marred by many false starts and unfulfilled promises. But modern medical science is now gradually closing in on what might realistically enable people to live longer, healthier lives — if they are willing to sacrifice some popular hedonistic pleasures. Specialists in the biology of aging have identified a rarely recognized yet universal condition that is a major contributor to a wide range of common health-robbing ailments, from heart disease, diabetes and cancer to arthritis, depression and Alzheimer’s disease. That condition is chronic inflammation, a kind of low-grade irritant that can undermine the well-being of virtually every bodily system. Ultimately, motivation is irrelevant—who cares if companies are merely pursuing the vegan pound, or if some self-declared “vegans” are self-obsessed wellness slaves ditching dairy for vanity’s sake? If they’re part of a movement that might help slam the brakes on impending environmental doom, then they are surely a force for good.

Ultimately, motivation is irrelevant—who cares if companies are merely pursuing the vegan pound, or if some self-declared “vegans” are self-obsessed wellness slaves ditching dairy for vanity’s sake? If they’re part of a movement that might help slam the brakes on impending environmental doom, then they are surely a force for good. And so, while the requirement for scientific and technical expertise about climate change cannot be denied, there are ways to reconcile this reality with the needs for inclusive, democratic processes about climate action. In his theory of deliberative democracy, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929-) provides a framework within which democratic processes can distinguish between the different dimensions of discourse – scientific-pragmatic and moral-political. In the context of climate change, this means that there are pathways to address the problem that don’t require scientific or technical expertise, and that are geared towards tackling the collective issues it raises democratically.

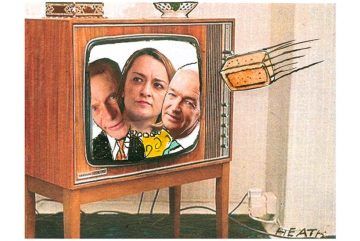

And so, while the requirement for scientific and technical expertise about climate change cannot be denied, there are ways to reconcile this reality with the needs for inclusive, democratic processes about climate action. In his theory of deliberative democracy, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929-) provides a framework within which democratic processes can distinguish between the different dimensions of discourse – scientific-pragmatic and moral-political. In the context of climate change, this means that there are pathways to address the problem that don’t require scientific or technical expertise, and that are geared towards tackling the collective issues it raises democratically. For the past several years, there has been a flood of commentary about how politics is poisoning social life, from first-person stories about “surviving” holidays or breaking off romantic relationships to surveys about the precipitous drop in inter-partisan friendships on college campuses. There are many who think this is a reasonable state of affairs: that “the personal is political” and that it is therefore only natural that all of a person’s social perceptions and choices be suffused with the eerie light of political analysis. But there are also those who dissent. These dissenters say that Americans need to relearn how to disagree with one another productively; the strength of our public dialogue and of our democratic process itself may depend, this crowd says, on our having more and better political discussion and more interactions with those outside our bubbles.

For the past several years, there has been a flood of commentary about how politics is poisoning social life, from first-person stories about “surviving” holidays or breaking off romantic relationships to surveys about the precipitous drop in inter-partisan friendships on college campuses. There are many who think this is a reasonable state of affairs: that “the personal is political” and that it is therefore only natural that all of a person’s social perceptions and choices be suffused with the eerie light of political analysis. But there are also those who dissent. These dissenters say that Americans need to relearn how to disagree with one another productively; the strength of our public dialogue and of our democratic process itself may depend, this crowd says, on our having more and better political discussion and more interactions with those outside our bubbles. It’s an unfashionable thought, but having spent many hours in the university sports hall where constituency votes for Boris Johnson and John McDonnell were counted, I feel freshly in love with democracy. There they all were, local councillors and party workers from across the spectrum; campaigners pursuing personal crusades, from animal rights to the way fathers are treated by the courts; eccentrics dressed as Time Lords. In the hot throng, there were extremists and a few who seemed frankly mad. But most were genial, thoughtful, balanced people giving of their free time to make this a slightly better country. Stuck in Westminster during relentless parliamentary crises, it’s easy to lose sight of just how energising real democracy is. I came home with my cynicism scrubbed off, and exhausted-refreshed.

It’s an unfashionable thought, but having spent many hours in the university sports hall where constituency votes for Boris Johnson and John McDonnell were counted, I feel freshly in love with democracy. There they all were, local councillors and party workers from across the spectrum; campaigners pursuing personal crusades, from animal rights to the way fathers are treated by the courts; eccentrics dressed as Time Lords. In the hot throng, there were extremists and a few who seemed frankly mad. But most were genial, thoughtful, balanced people giving of their free time to make this a slightly better country. Stuck in Westminster during relentless parliamentary crises, it’s easy to lose sight of just how energising real democracy is. I came home with my cynicism scrubbed off, and exhausted-refreshed. At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation?

At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof. It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation? Sanjay Reddy in The Print:

Sanjay Reddy in The Print: