Corey Robin in the New York Review of Books:

It has been more than two weeks since the Iowa caucuses, and we still don’t know who won. That should give us pause. We don’t know in part because of a combination of technological failing and human error. But we’re also in the dark for a political reason. That should give us further pause.

No one disputes that Bernie Sanders won the most votes in Iowa. Yet Pete Buttigieg has the most delegates. While experts continue to parse the flaws in the reporting process, the stark and simple fact that more voters supported Sanders than any other candidate somehow remains irrelevant, obscure.

America’s democratic reflexes have grown sluggish. Not only has the loser of the popular vote won two out of the last five presidential elections, but come November, he may win a third. Like the children of alcoholics, we’ve learned to live with the situation, adjusting ourselves to the tyranny of its effects. We don’t talk anymore about who will win the popular vote in the coming election. We calculate which candidate will win enough votes in the right states to secure a majority in the Electoral College. Perhaps that’s why the scandal coming out of Iowa is the app that failed and the funky math of the precinct counters—and not the democratic embarrassment that the winner of the most votes doesn’t automatically win the most delegates.

More here.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19. BREATHING FINE PARTICLES

BREATHING FINE PARTICLES Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.”

Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.” The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted.

The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted. Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility.

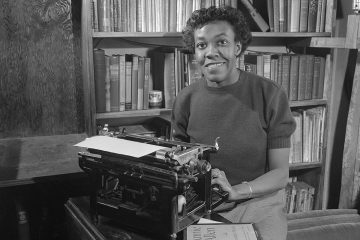

Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility. The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes:

The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes: As I write this, Sydney, the city where I’ve set my life and much of my fiction over the past 27 years, is ringed by fire and choked by smoke. A combination fan and air purifier hums in the corner of my study. Seretide and Ventolin inhalers sit within reach on my desk. I’m surrounded by a lifetime’s accumulation of books, including some relatively rare and specialist volumes on China, in English and Chinese. This library might not be precious in monetary terms, but it’s priceless to me and vital to my work. I wonder which books I would save if I had to pack a car quickly and go. The thought of people making those decisions right now, including people I know, twists my gut.

As I write this, Sydney, the city where I’ve set my life and much of my fiction over the past 27 years, is ringed by fire and choked by smoke. A combination fan and air purifier hums in the corner of my study. Seretide and Ventolin inhalers sit within reach on my desk. I’m surrounded by a lifetime’s accumulation of books, including some relatively rare and specialist volumes on China, in English and Chinese. This library might not be precious in monetary terms, but it’s priceless to me and vital to my work. I wonder which books I would save if I had to pack a car quickly and go. The thought of people making those decisions right now, including people I know, twists my gut. It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time.

It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time. To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods.

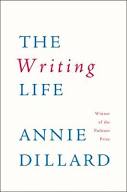

To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods. If self-help books soothe people whose lives feel like open wounds, there’s perhaps no class of people who needs the category more than writers do. It was only lately that I realized I was drawn to self-improvement books, and the certainty they sell, because I was a writer—because the life of a writer is marked by insecurity both emotional and financial, rejection at seemingly every turn, and the fact that no one has any idea what you’re talking about when you say writing is hard and you hate it. I think of Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, who says as much to a local ferryman and then hastily backtracks. “But I rallied and mustered and said that the idea was to learn things; that you learn a thing and then as a matter of course you learn the next thing, and the next thing,” she writes. “As I spoke he nodded precisely in the way that one nods at the utterances of the deranged. ‘And then,’ I finished brightly, ‘you die!’”

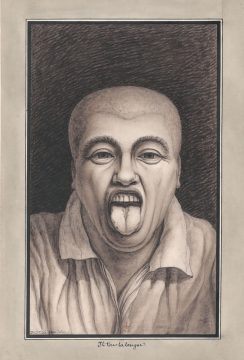

If self-help books soothe people whose lives feel like open wounds, there’s perhaps no class of people who needs the category more than writers do. It was only lately that I realized I was drawn to self-improvement books, and the certainty they sell, because I was a writer—because the life of a writer is marked by insecurity both emotional and financial, rejection at seemingly every turn, and the fact that no one has any idea what you’re talking about when you say writing is hard and you hate it. I think of Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, who says as much to a local ferryman and then hastily backtracks. “But I rallied and mustered and said that the idea was to learn things; that you learn a thing and then as a matter of course you learn the next thing, and the next thing,” she writes. “As I spoke he nodded precisely in the way that one nods at the utterances of the deranged. ‘And then,’ I finished brightly, ‘you die!’” Like other early-modern architects, Lequeu’s drawings explore analogies between bodies and buildings and the erotic, multisensory dimensions of architectural design. In his annotations, he often describes in compulsive detail not only how buildings look but also how they feel, smell, and even taste—which admittedly sounds weird until you read Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Le génie de l’architecture, ou L’analogie de cet art avec nos sensations (The Genius of Architecture; or, The Analogy of That Art with Our Sensations, 1780), a building treatise informed by eighteenth-century sensationalist and materialist philosophy, or Jean-François de Bastide’s La petite maison (The Little House, 1758). The latter text, a libertine novella centering on a marquis who bets a young ingénue that he can seduce her by taking her on a tour of his “pleasure house” (maison de plaisance) outside of Paris, contains descriptions of scented walls and furnishings, a mechanical dining table that drops through a trapdoor, and a mirrored boudoir disguised as a trompe l’oeil forest that readily call to mind the drawings of Lequeu.

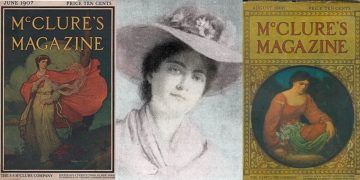

Like other early-modern architects, Lequeu’s drawings explore analogies between bodies and buildings and the erotic, multisensory dimensions of architectural design. In his annotations, he often describes in compulsive detail not only how buildings look but also how they feel, smell, and even taste—which admittedly sounds weird until you read Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Le génie de l’architecture, ou L’analogie de cet art avec nos sensations (The Genius of Architecture; or, The Analogy of That Art with Our Sensations, 1780), a building treatise informed by eighteenth-century sensationalist and materialist philosophy, or Jean-François de Bastide’s La petite maison (The Little House, 1758). The latter text, a libertine novella centering on a marquis who bets a young ingénue that he can seduce her by taking her on a tour of his “pleasure house” (maison de plaisance) outside of Paris, contains descriptions of scented walls and furnishings, a mechanical dining table that drops through a trapdoor, and a mirrored boudoir disguised as a trompe l’oeil forest that readily call to mind the drawings of Lequeu. Viola Roseboro’ (apostrophe intentional), the larger-than-life fiction editor at McClure’s, haunted magazine offices from the 1890s to the Jazz Age. A reader, editor, and semiprofessional wit, she discovered or mentored O. Henry, Willa Cather, and Jack London, among many others. Today she is nearly completely forgotten.

Viola Roseboro’ (apostrophe intentional), the larger-than-life fiction editor at McClure’s, haunted magazine offices from the 1890s to the Jazz Age. A reader, editor, and semiprofessional wit, she discovered or mentored O. Henry, Willa Cather, and Jack London, among many others. Today she is nearly completely forgotten. When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true?

When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true? They asked Katherine Johnson for the moon, and she gave it to them. Wielding little more than a pencil, a slide rule and one of the finest mathematical minds in the country, Mrs. Johnson, who died at 101 on Monday at a retirement home in Newport News, Va., calculated the precise trajectories that would let Apollo 11 land on the moon in 1969 and, after Neil Armstrong’s history-making moonwalk, let it return to Earth. A single error, she well knew, could have dire consequences for craft and crew. Her impeccable calculations had already helped plot the successful flight of Alan B. Shepard Jr., who became the first American in space when his Mercury spacecraft went aloft in 1961. The next year, she likewise helped make it possible for John Glenn, in the Mercury vessel Friendship 7, to become the first American to orbit the Earth. Yet throughout Mrs. Johnson’s 33 years in NASA’s Flight Research Division — the office from which the American space program sprang — and for decades afterward, almost no one knew her name.

They asked Katherine Johnson for the moon, and she gave it to them. Wielding little more than a pencil, a slide rule and one of the finest mathematical minds in the country, Mrs. Johnson, who died at 101 on Monday at a retirement home in Newport News, Va., calculated the precise trajectories that would let Apollo 11 land on the moon in 1969 and, after Neil Armstrong’s history-making moonwalk, let it return to Earth. A single error, she well knew, could have dire consequences for craft and crew. Her impeccable calculations had already helped plot the successful flight of Alan B. Shepard Jr., who became the first American in space when his Mercury spacecraft went aloft in 1961. The next year, she likewise helped make it possible for John Glenn, in the Mercury vessel Friendship 7, to become the first American to orbit the Earth. Yet throughout Mrs. Johnson’s 33 years in NASA’s Flight Research Division — the office from which the American space program sprang — and for decades afterward, almost no one knew her name.

It is the end of the Trojan War. Hecuba, the noble queen of Troy, has endured many losses: her husband, her children, her fatherland, destroyed by fire. And yet she remains an admirable person—loving, capable of trust and friendship, combining autonomous action with extensive concern for others. But then she suffers a betrayal that cuts deep, traumatizing her entire personality. A close friend, Polymestor, to whom she has entrusted the care of her last remaining child, murders the child for money. That is the central event in Euripides’s Hecuba (424 BCE), an anomalous version of the Trojan war story, shocking in its moral ugliness, and yet one of the most insightful dramas in the tragic canon.

It is the end of the Trojan War. Hecuba, the noble queen of Troy, has endured many losses: her husband, her children, her fatherland, destroyed by fire. And yet she remains an admirable person—loving, capable of trust and friendship, combining autonomous action with extensive concern for others. But then she suffers a betrayal that cuts deep, traumatizing her entire personality. A close friend, Polymestor, to whom she has entrusted the care of her last remaining child, murders the child for money. That is the central event in Euripides’s Hecuba (424 BCE), an anomalous version of the Trojan war story, shocking in its moral ugliness, and yet one of the most insightful dramas in the tragic canon.