R. J. Lipton in Gödel’s Lost Letter and P = NP:

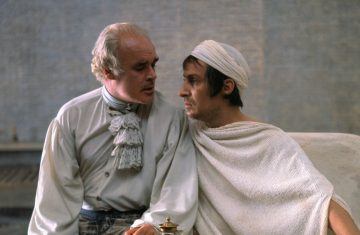

Dr. Strangelove is the classic 1964 movie about the potential for nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union during the cold war. The film was directed by Stanley Kubrick and stars Peter Sellers, George Scott, Sterling Hayden, and Slim Pickens.

Today we try to explain the P=NP problem in an “analog” fashion.

In Dr. Strangelove, US President Merkin Muffley wishes to recall a group of US bombers that are incorrectly about to drop nuclear weapons on Russia. He hopes to stop war. Here is the conversation between General Turgidson played by Scott and Muffley played by Sellers, in which Turgidson informs that the recall message will not be received…

Turgidson: …unless the message is preceded by the correct three-letter prefix.

Muffley: Then do you mean to tell me, General Turgidson, that you will be unable to recall the aircraft?

Turgidson: That’s about the size of it. However, we are plowing through every possible three letter combination of the code. But since there are seventeen thousand permutations it’s going to take us about two and a half days to transmit them all.

Muffley: How soon did you say the planes would penetrate Russian radar cover?

Turgidson: About eighteen minutes from now, sir.

This is the problem that P=NP addresses. How do you find a solution to a problem that has many potential solutions? In this case there are over thousands of possible combinations. Since each requires sending a message to an electronic unit that sits on a plane, thousands of miles away, and since messages cannot be sent too often, it will take much too long to find the secret message.

The central P=NP question is: Can we do better than trying all possibilities? The answer is yes—at least in the case of the movie, the secret combination is indeed found. More on that in a moment.

More here.

It is a journalistic convention that any author who writes a doorstopper of a book with the word “capital” in the title must be the heir to Karl Marx, while any economist whose books sell in the hundreds of thousands is a “rock star”. Thomas Piketty’s 600-page, multi-million selling

It is a journalistic convention that any author who writes a doorstopper of a book with the word “capital” in the title must be the heir to Karl Marx, while any economist whose books sell in the hundreds of thousands is a “rock star”. Thomas Piketty’s 600-page, multi-million selling  The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize, Lowell’s second, in 1974. It also sparked controversy, due not only to Lowell’s portrayal of Hardwick as the aggrieved, abandoned wife—the “Lizzie character,” as he called her—whom he unflatteringly contrasts throughout to the fecund Caroline character, variously imagined as dolphin, mermaid, and baby killer whale—but also due to his appropriation, and changing, of Hardwick’s letters into sonnets that voice the wife’s side of the story, whether as letter-poems or admonitory echoes that surface in the Lowell character’s head. The awkwardness here of referring to real people as characters reflects the inherent problem with Lowell’s book: the line between fact and fiction is stretched so thin—even to the point of “character” names corresponding to those of their real-life counterparts—that readers are led to assume that the book chronicles reality, not fiction, despite Lowell’s equivocal disclaimer in the final, title poem that the book is “half fiction.”

The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize, Lowell’s second, in 1974. It also sparked controversy, due not only to Lowell’s portrayal of Hardwick as the aggrieved, abandoned wife—the “Lizzie character,” as he called her—whom he unflatteringly contrasts throughout to the fecund Caroline character, variously imagined as dolphin, mermaid, and baby killer whale—but also due to his appropriation, and changing, of Hardwick’s letters into sonnets that voice the wife’s side of the story, whether as letter-poems or admonitory echoes that surface in the Lowell character’s head. The awkwardness here of referring to real people as characters reflects the inherent problem with Lowell’s book: the line between fact and fiction is stretched so thin—even to the point of “character” names corresponding to those of their real-life counterparts—that readers are led to assume that the book chronicles reality, not fiction, despite Lowell’s equivocal disclaimer in the final, title poem that the book is “half fiction.” Ninagawa would’ve hated being called my favorite self-Orientalist. He would’ve thrown an ashtray at me, if the stuff of legends is true. He did not brook critiques that hinted at his dabbling in the “Japanesque.” Ninagawa’s audience—his only audience, he maintained—was the Japanese, his aim “to produce a Shakespeare play that could be understood by ordinary people.” He said this with an air of finality, as if slamming a door shut, but I always wanted to jam a foot in before he did. I needed definitions—for “ordinary” and “Japanese”—his full-throated definitions, though he’d died before giving them. Because seeing his art had taught generations to stretch the bounds of those two words beyond imagining. No, here’s a more honest, selfish reason than that: I needed to know whether he was speaking to people who found them both comforting and troubling. I needed to know whether he was speaking to people like me.

Ninagawa would’ve hated being called my favorite self-Orientalist. He would’ve thrown an ashtray at me, if the stuff of legends is true. He did not brook critiques that hinted at his dabbling in the “Japanesque.” Ninagawa’s audience—his only audience, he maintained—was the Japanese, his aim “to produce a Shakespeare play that could be understood by ordinary people.” He said this with an air of finality, as if slamming a door shut, but I always wanted to jam a foot in before he did. I needed definitions—for “ordinary” and “Japanese”—his full-throated definitions, though he’d died before giving them. Because seeing his art had taught generations to stretch the bounds of those two words beyond imagining. No, here’s a more honest, selfish reason than that: I needed to know whether he was speaking to people who found them both comforting and troubling. I needed to know whether he was speaking to people like me. In October 1726 some ‘strange, but well attested’ news emerged from Godalming near Guildford. An ‘eminent’ surgeon, a male midwife, had delivered a poor woman called Mary Toft not of a child but of rabbits – a number of them, over a period of several weeks. None of the rabbits, not even a ‘perfect’ one, survived their birth, but the surgeon bottled them up and declared his intention to present them as specimens to the Royal Society. A report in the British Gazeteer furnished readers with the woman’s explanation. Some months earlier she and other women working in a field had chased a rabbit and failed to catch it. She was pregnant at the time and suffered a miscarriage. Thereafter, she pined to eat rabbit and had been unable to avoid thinking of rabbits.

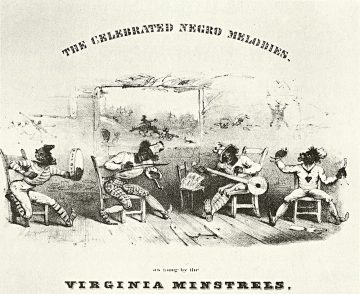

In October 1726 some ‘strange, but well attested’ news emerged from Godalming near Guildford. An ‘eminent’ surgeon, a male midwife, had delivered a poor woman called Mary Toft not of a child but of rabbits – a number of them, over a period of several weeks. None of the rabbits, not even a ‘perfect’ one, survived their birth, but the surgeon bottled them up and declared his intention to present them as specimens to the Royal Society. A report in the British Gazeteer furnished readers with the woman’s explanation. Some months earlier she and other women working in a field had chased a rabbit and failed to catch it. She was pregnant at the time and suffered a miscarriage. Thereafter, she pined to eat rabbit and had been unable to avoid thinking of rabbits. Minstrel shows, most often with white entertainers performing in blackface, were a highly racist phenomenon that were a pervasive form of entertainment in America for over 80 years through the 1800s and early 1900s. Yet as complicated and fundamentally offensive as they were, it was part of what led to a break with a purely European music tradition: “African Americans were leading the way in breaking with European musical tradition, and, strange as it might seem, this break had been anticipated, and maybe even urged, by the minstrel show, the first form of musical theater to reach the whole country. Its history is much longer than the eighty or so years that it is said to have lasted in the United States; its legacy is far more complicated than just a matter of white people copying black people, and even today questions about the sources of this music and its influence remain unsettled.

Minstrel shows, most often with white entertainers performing in blackface, were a highly racist phenomenon that were a pervasive form of entertainment in America for over 80 years through the 1800s and early 1900s. Yet as complicated and fundamentally offensive as they were, it was part of what led to a break with a purely European music tradition: “African Americans were leading the way in breaking with European musical tradition, and, strange as it might seem, this break had been anticipated, and maybe even urged, by the minstrel show, the first form of musical theater to reach the whole country. Its history is much longer than the eighty or so years that it is said to have lasted in the United States; its legacy is far more complicated than just a matter of white people copying black people, and even today questions about the sources of this music and its influence remain unsettled. Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years.

Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years. Numbers have a certain mystique: They seem precise, exact, sometimes even beyond doubt. But outside the field of pure mathematics, this reputation rarely is deserved. And when it comes to the coronavirus epidemic, buying into that can be downright dangerous.

Numbers have a certain mystique: They seem precise, exact, sometimes even beyond doubt. But outside the field of pure mathematics, this reputation rarely is deserved. And when it comes to the coronavirus epidemic, buying into that can be downright dangerous. More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear.

More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear. We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” (

We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” ( Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

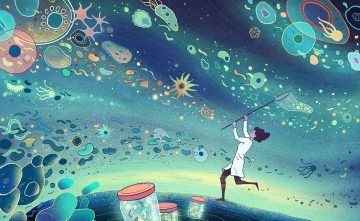

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.”

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.” Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market.

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market.