Diaspora

If the meaning of the prayer was not passed down to you,

find it through holier means than translation.

Cling to the rhythm instead.

If you were not taught the rhythm, memorize the clang

of knife against yam against wooden cutting board.

Keep it ringing, ringing in your ears.

If not the ring,

then the Bombay jazz club

and its green lanterns swaying in the long, long night

If you were not given the religion, then at least

Boompa’s rosary beads,

with their memories

indented in thick amber,

the gold Zarathustra hanging from a neck

and tattooed on a sunburnt back.

If the traditions were never taught to you,

then cling to tea time always served at 2pm.

Display the cups and remember

elders do not take their tea with sugar,

like you do.

You have only a fraction of their blood.

You thicken your water with milk.

If home did not fit in the carry on compartment,

then the sprigs of lemongrass from the garden will do.

The tea bags brought from India will do.

The reusable garland will do.

The passport’s golden lions

show a compass of 3 directions.

The fourth will do, too.

With its back facing you,

and its open jaws the homeland.

If the orthodox genealogy did not show up to the altar

of any of the son’s weddings, identity will celebrate

the melting pot mothers. Inheritance

blooms a grateful garland

around the brownish baby’s plump smile.

Her laughter, an anthem.

Her heartbeat, a golden rhythm.

by Azura Tyabji

from Split This Rock

You may have noticed that there are a lot of writers writing a lot about the coronavirus. As every day passes, I want to read these pieces less and less. I don’t care about the subtleties of your daily experience under lockdown, Sensitive Writer Person. I don’t care about your analysis of how everything is going to change or about how everything is actually not really going to change, Journalist. I am indifferent as to your recommendations, Pundit. I give not a crap about your brilliant reading of Camus in light of COVID-19, Essayist. I’m in a boycott, a deep boycott. I will read nothing about coronavirus until 2030; this is my current and most solemn pledge.

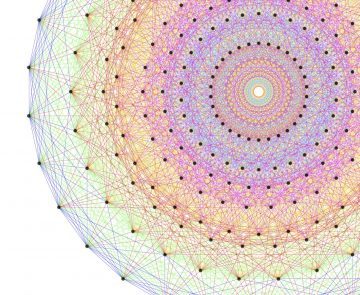

You may have noticed that there are a lot of writers writing a lot about the coronavirus. As every day passes, I want to read these pieces less and less. I don’t care about the subtleties of your daily experience under lockdown, Sensitive Writer Person. I don’t care about your analysis of how everything is going to change or about how everything is actually not really going to change, Journalist. I am indifferent as to your recommendations, Pundit. I give not a crap about your brilliant reading of Camus in light of COVID-19, Essayist. I’m in a boycott, a deep boycott. I will read nothing about coronavirus until 2030; this is my current and most solemn pledge. When representation theory emerged in the late 19th century, many mathematicians questioned its worth. In 1897, the English mathematician William Burnside wrote that he doubted that this unorthodox perspective would yield any new results at all.

When representation theory emerged in the late 19th century, many mathematicians questioned its worth. In 1897, the English mathematician William Burnside wrote that he doubted that this unorthodox perspective would yield any new results at all. Tear gas rounds describe a graceful arc as they drop down out of the blue sky, trailing feathery tails of smoke like streamers. The shells hit the road with a ping, and sparks fly as they skip gaily along the asphalt. As they roll to a stop, the shells hiss like an angry snake, dense smoke pouring out of the top of the small aluminum canister, and soon the street is enveloped in clouds.

Tear gas rounds describe a graceful arc as they drop down out of the blue sky, trailing feathery tails of smoke like streamers. The shells hit the road with a ping, and sparks fly as they skip gaily along the asphalt. As they roll to a stop, the shells hiss like an angry snake, dense smoke pouring out of the top of the small aluminum canister, and soon the street is enveloped in clouds. I first discovered

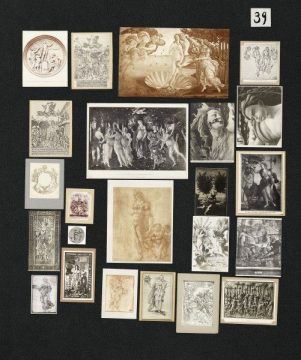

I first discovered  It was only in the second volume of Warburg’s Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), published in 2000, that the glass negatives created in 1929 were used to publish fragmentary pictorial evidence of the “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.” Editors Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink produced black-and-white images from the negatives, printing them at a reduced size that tended to obscure their details. They also left off additional commentary, given the lack of extant captioning by Warburg himself. This publication was in no small part encouraged by the resurgence of interest in the works of Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), whose theories of media and history had come to seem prescient, particularly in the Anglophone world, with the 1969 Illuminations, edited and introduced by Hannah Arendt and subsequently popularized by John Berger in his 1972 TV series and book, Ways of Seeing. (While Warburg was only peripherally aware of Benjamin during his lifetime, Benjamin sent Warburg a copy of his thesis on Baroque Trauerspiel, or tragic drama, which cited Warburg.) Like Benjamin, who often engaged in leaps of thought and argument by way of metaphorical image rather than logical deduction, Warburg was concerned with Zwischenräume, the spaces in between, as well as something he termed Denkraum, or room for thought.

It was only in the second volume of Warburg’s Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), published in 2000, that the glass negatives created in 1929 were used to publish fragmentary pictorial evidence of the “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.” Editors Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink produced black-and-white images from the negatives, printing them at a reduced size that tended to obscure their details. They also left off additional commentary, given the lack of extant captioning by Warburg himself. This publication was in no small part encouraged by the resurgence of interest in the works of Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), whose theories of media and history had come to seem prescient, particularly in the Anglophone world, with the 1969 Illuminations, edited and introduced by Hannah Arendt and subsequently popularized by John Berger in his 1972 TV series and book, Ways of Seeing. (While Warburg was only peripherally aware of Benjamin during his lifetime, Benjamin sent Warburg a copy of his thesis on Baroque Trauerspiel, or tragic drama, which cited Warburg.) Like Benjamin, who often engaged in leaps of thought and argument by way of metaphorical image rather than logical deduction, Warburg was concerned with Zwischenräume, the spaces in between, as well as something he termed Denkraum, or room for thought. The style of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is more restrained and controlled than these earlier works, but full of well-noticed contrasting details that combine to create an effect that Guibert—apropos of The Compassion Protocol, his last work before his suicide in 1991—characterized as “barbarous and delicate.” An ambulance pulls up to unload a patient in front of a half-abandoned hospital in the midst of shutting down: “slippers in a crate with ampules of potassium chloride . . . a basin from an intensive care unit with a coating of snow on the bottom.” At another hospital, the nurses who draw his blood for the dreaded regular T-cell count “slip on their latex gloves as though they were velvet gloves for a gala evening at the opera.” One of them comments on his cologne, “It’s Habit Rouge isn’t it? . . . I do like that perfume, and to catch a whiff of it on this gray morning, well, you know it’s really a little treat for me.” Disease, as those who’ve spent time in the presence of the sick know, is never quite dramatically life or death, but always life in death and death in life. No moment of one’s life as a terminally ill person or a carer for a terminally ill person passes without this double acknowledgment.

The style of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is more restrained and controlled than these earlier works, but full of well-noticed contrasting details that combine to create an effect that Guibert—apropos of The Compassion Protocol, his last work before his suicide in 1991—characterized as “barbarous and delicate.” An ambulance pulls up to unload a patient in front of a half-abandoned hospital in the midst of shutting down: “slippers in a crate with ampules of potassium chloride . . . a basin from an intensive care unit with a coating of snow on the bottom.” At another hospital, the nurses who draw his blood for the dreaded regular T-cell count “slip on their latex gloves as though they were velvet gloves for a gala evening at the opera.” One of them comments on his cologne, “It’s Habit Rouge isn’t it? . . . I do like that perfume, and to catch a whiff of it on this gray morning, well, you know it’s really a little treat for me.” Disease, as those who’ve spent time in the presence of the sick know, is never quite dramatically life or death, but always life in death and death in life. No moment of one’s life as a terminally ill person or a carer for a terminally ill person passes without this double acknowledgment. ALONE AND INSIDE IN THESE

ALONE AND INSIDE IN THESE  Human beings typically don’t leave the nest until well into our teenage years—a relatively rare strategy among animals. But corvids—a group of birds that includes jays, ravens, and crows—also spend a lot of time under their parents’ wings. Now, in a parallel to humans, researchers have found that ongoing tutelage by patient parents may explain how corvids have managed to achieve their smarts. Corvids are large, big-brained birds that often live in intimate social groups of related and unrelated individuals. They are known to be intelligent—capable of

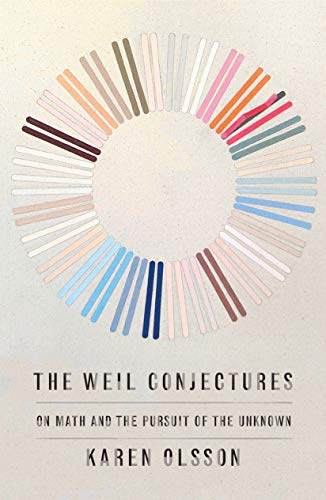

Human beings typically don’t leave the nest until well into our teenage years—a relatively rare strategy among animals. But corvids—a group of birds that includes jays, ravens, and crows—also spend a lot of time under their parents’ wings. Now, in a parallel to humans, researchers have found that ongoing tutelage by patient parents may explain how corvids have managed to achieve their smarts. Corvids are large, big-brained birds that often live in intimate social groups of related and unrelated individuals. They are known to be intelligent—capable of  In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians.

In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians. Late one January

Late one January If we’re talking about culture that makes people happy, we have to start with the works of PG Wodehouse. There are two reasons why. One reason is that making people happy was Wodehouse’s overriding ambition. The other reason is that he was better at it than any other writer in history.

If we’re talking about culture that makes people happy, we have to start with the works of PG Wodehouse. There are two reasons why. One reason is that making people happy was Wodehouse’s overriding ambition. The other reason is that he was better at it than any other writer in history. What does it mean to be great? Whom shall we call great? How can we become great? Is greatness the same as goodness? These questions involve fundamental ethical assumptions, concepts and concerns. Like many who addressed such issues in the past, we often use virtues — courage, generosity, forbearance, etc. — in order to explain what greatness means, reflecting a common notion that greatness requires moral integrity. Virtues describe our ambitions and aspirations, as individuals and as communities. How we give credit for moral achievements is presumably also culturally conditioned, just as the way we relate to our accomplishments in general reflects social and historical context. Studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect suggest that while North Americans regularly overestimate their abilities, in Japan the opposite appears to be the case. Other variables too are sometimes debated. The self-citation rate among male scientists is often reported to be higher than among their female peers, which might reflect a higher estimation of their achievements. Differences are also believed to be generational and related to educational practices around appreciation and rewards. Recent public debates have shed light on the psychological and emotional costs of self-optimizing and the social and political dynamics of virtue-signaling. Likewise, who our role models should be and how they are selected often reveals the diverging views of greatness in a society. Even a brief survey of these and similar discussions suggests that the philosophical problem of greatness can be of significant interest to contemporary readers.

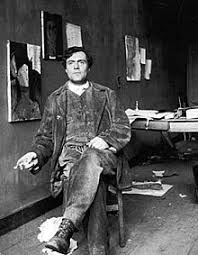

What does it mean to be great? Whom shall we call great? How can we become great? Is greatness the same as goodness? These questions involve fundamental ethical assumptions, concepts and concerns. Like many who addressed such issues in the past, we often use virtues — courage, generosity, forbearance, etc. — in order to explain what greatness means, reflecting a common notion that greatness requires moral integrity. Virtues describe our ambitions and aspirations, as individuals and as communities. How we give credit for moral achievements is presumably also culturally conditioned, just as the way we relate to our accomplishments in general reflects social and historical context. Studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect suggest that while North Americans regularly overestimate their abilities, in Japan the opposite appears to be the case. Other variables too are sometimes debated. The self-citation rate among male scientists is often reported to be higher than among their female peers, which might reflect a higher estimation of their achievements. Differences are also believed to be generational and related to educational practices around appreciation and rewards. Recent public debates have shed light on the psychological and emotional costs of self-optimizing and the social and political dynamics of virtue-signaling. Likewise, who our role models should be and how they are selected often reveals the diverging views of greatness in a society. Even a brief survey of these and similar discussions suggests that the philosophical problem of greatness can be of significant interest to contemporary readers. The cultured and literate Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) was passionately interested in and emotionally involved with Italian and French poetry of the past as well as with the work of his friends, Anna Ahkmatova, Max Jacob and Blaise Cendrars. On the 100th anniversary of his tragic death in 1920 we can see how the poets who fascinated him portrayed the pain of sex and love, the exaltation of art, the effect of narcotics on creativity and the need to suffer extreme experience. They encouraged his compulsion to live dangerously, and taught him to see the artist as victim, outcast and superman. They provided intellectual justification for the deliberate derangement of his senses and glorified his devotion to art. He didn’t just read poets. He lived according to their principles as if they were imprinted on his body as well as in his mind. These powerful poets both inspired his work and—as he was drawn to disaster and followed their maniacal descent–helped to destroy him.

The cultured and literate Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) was passionately interested in and emotionally involved with Italian and French poetry of the past as well as with the work of his friends, Anna Ahkmatova, Max Jacob and Blaise Cendrars. On the 100th anniversary of his tragic death in 1920 we can see how the poets who fascinated him portrayed the pain of sex and love, the exaltation of art, the effect of narcotics on creativity and the need to suffer extreme experience. They encouraged his compulsion to live dangerously, and taught him to see the artist as victim, outcast and superman. They provided intellectual justification for the deliberate derangement of his senses and glorified his devotion to art. He didn’t just read poets. He lived according to their principles as if they were imprinted on his body as well as in his mind. These powerful poets both inspired his work and—as he was drawn to disaster and followed their maniacal descent–helped to destroy him. Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher

Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher