Lawrence Wright in The New Yorker:

Italy at the beginning of the fourteenth century was a conglomeration of prosperous city-states that had broken free of the feudal system. Some of them, such as Venice, formed merchant republics, which became seedbeds for capitalism. Venice and other coastal cities, including Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi, set up trading networks and established outposts throughout the Mediterranean and as far away as the Black Sea. Other Italian cities, such as Bologna, became free communes, which meant that peasants fleeing feudal estates were granted freedom once they entered the city walls. Serfs became artisans. A middle class began to form. The early fourteenth century was robust and ambitious. Then, suddenly, people began to die.

Italy at the beginning of the fourteenth century was a conglomeration of prosperous city-states that had broken free of the feudal system. Some of them, such as Venice, formed merchant republics, which became seedbeds for capitalism. Venice and other coastal cities, including Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi, set up trading networks and established outposts throughout the Mediterranean and as far away as the Black Sea. Other Italian cities, such as Bologna, became free communes, which meant that peasants fleeing feudal estates were granted freedom once they entered the city walls. Serfs became artisans. A middle class began to form. The early fourteenth century was robust and ambitious. Then, suddenly, people began to die.

Bologna was a stronghold of medical teaching. The city’s famous university, established in 1088, is the oldest in the world. “What they had we call scholastic medicine,” Pomata told me. “When we say ‘scholastic,’ we mean something that is very abstract, not concrete, not empirical.” European scholars at the time studied a number of classical physicians—including Hippocrates, the Greek philosopher of the fifth century B.C. who is considered the father of medicine, and Galen, the second-century Roman who was the most influential medical figure in antiquity—but scholastic medicine was confounded with astrological notions. When the King of France sought to understand the cause of the plague, the medical faculty at the University of Paris blamed a triple conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars in the fortieth degree of Aquarius, which had occurred on March 20, 1345.

…Before arriving in Italy, the rampaging contagion had already killed millions of people as it burned through China, Russia, India, Persia, Syria, and Asia Minor. It was said that there were entire territories where nobody was left alive. The source of the disease was sometimes thought to be “miasma,” or air that was considered unhealthy, such as sea breezes. Paradoxically, there was also a folk belief that attendants who cleaned latrines were immune, which led some people to confine themselves for hours a day amid human waste, absorbing the presumed medicinal odors.

More here.

Peter Beinart, a professor of journalism at the City University of New York, has caused a stir in the past week with articles and interviews in which he says he has given up on the project of a Jewish state in Israel. He still likes the idea of a Jewish “homeland.” What clearly drives his position is the collapse of the two-state solution around the year 2000. By now it is clear that there cannot be a Palestinian state, what with 650,000 Israeli settlers in the Palestinian West Bank (if you count the parts of it that Israel annexed and made part of its district of Jerusalem). Not only that, but the rise of an Israeli illiberalism inside Israel proper that is determined to make the over 20% of the population that is not Jewish permanent second-class citizens underlines for him that Jewish power as now configured as a zero-sum game. Jews have rights, citizenship, and sovereignty inside Israel; non-Jews have no sovereignty even though they are Israeli citizens, and their rights are fewer.

Peter Beinart, a professor of journalism at the City University of New York, has caused a stir in the past week with articles and interviews in which he says he has given up on the project of a Jewish state in Israel. He still likes the idea of a Jewish “homeland.” What clearly drives his position is the collapse of the two-state solution around the year 2000. By now it is clear that there cannot be a Palestinian state, what with 650,000 Israeli settlers in the Palestinian West Bank (if you count the parts of it that Israel annexed and made part of its district of Jerusalem). Not only that, but the rise of an Israeli illiberalism inside Israel proper that is determined to make the over 20% of the population that is not Jewish permanent second-class citizens underlines for him that Jewish power as now configured as a zero-sum game. Jews have rights, citizenship, and sovereignty inside Israel; non-Jews have no sovereignty even though they are Israeli citizens, and their rights are fewer.

Like many a subsequent empire, Rome had a highly ambivalent relationship with the outsiders it needed to fuel its commerce, stock its slave markets and man its armies. In this particular case, those outsiders were not colonised peoples but the Germanic barbarian tribes living in areas against which the waves of Roman imperialism had only lapped during the empire’s high tide, before it began to recede in the third century. The Danube basin, where Alaric grew up in the 370s, seems from Boin’s account an idyllic place: his family home bore the bucolic name Pine Tree Island and Boin conjures an image of infant Goths listening to tales of their heroic ancestor King Berig, who had led his people – perhaps understandably – out of a homeland of ‘quaking bogs’ called Scandza. Yet it was also a place of profound danger: of slave traders who kidnapped young girls in order to sell them south of the river, of ghosts and demons and, most threatening of all, of predatory Roman officials whose actions in trying to starve would-be migrants who were crossing the imperial frontier led to the first mass Gothic raids on the Balkans.

Like many a subsequent empire, Rome had a highly ambivalent relationship with the outsiders it needed to fuel its commerce, stock its slave markets and man its armies. In this particular case, those outsiders were not colonised peoples but the Germanic barbarian tribes living in areas against which the waves of Roman imperialism had only lapped during the empire’s high tide, before it began to recede in the third century. The Danube basin, where Alaric grew up in the 370s, seems from Boin’s account an idyllic place: his family home bore the bucolic name Pine Tree Island and Boin conjures an image of infant Goths listening to tales of their heroic ancestor King Berig, who had led his people – perhaps understandably – out of a homeland of ‘quaking bogs’ called Scandza. Yet it was also a place of profound danger: of slave traders who kidnapped young girls in order to sell them south of the river, of ghosts and demons and, most threatening of all, of predatory Roman officials whose actions in trying to starve would-be migrants who were crossing the imperial frontier led to the first mass Gothic raids on the Balkans. Italy at the beginning of the fourteenth century was a conglomeration of prosperous city-states that had broken free of the feudal system. Some of them, such as Venice, formed merchant republics, which became seedbeds for capitalism. Venice and other coastal cities, including Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi, set up trading networks and established outposts throughout the Mediterranean and as far away as the Black Sea. Other Italian cities, such as Bologna, became free communes, which meant that peasants fleeing feudal estates were granted freedom once they entered the city walls. Serfs became artisans. A middle class began to form. The early fourteenth century was robust and ambitious. Then, suddenly, people began to die.

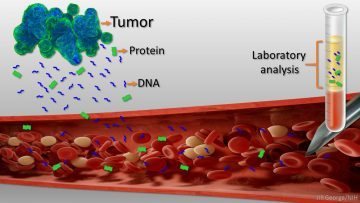

Italy at the beginning of the fourteenth century was a conglomeration of prosperous city-states that had broken free of the feudal system. Some of them, such as Venice, formed merchant republics, which became seedbeds for capitalism. Venice and other coastal cities, including Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi, set up trading networks and established outposts throughout the Mediterranean and as far away as the Black Sea. Other Italian cities, such as Bologna, became free communes, which meant that peasants fleeing feudal estates were granted freedom once they entered the city walls. Serfs became artisans. A middle class began to form. The early fourteenth century was robust and ambitious. Then, suddenly, people began to die. Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized. Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?

Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?

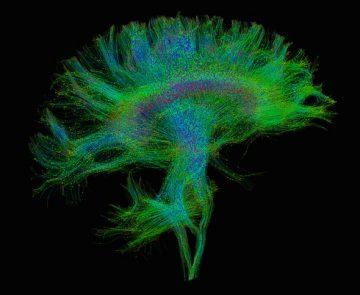

What makes the human brain special? That question is not easy to answer—and will occupy neuroscientists for generations to come. But a few tentative responses can already be mustered. The organ is certainly bigger than expected for our body size. And it has its own specialized areas—one of which is devoted to processing language. In recent years, brain scans have started to show that the particular way neurons connect to one another is also part of the story. A key tool in these studies is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—in particular, a version known as diffusion tensor imaging. This technique can visualize the long fibers that extend out from neurons and link brain regions without having to remove a piece of skull. Like wires, these connections carry electrical information between neurons. And the aggregate of all these links, also known as a connectome, can provide clues about how the brain processes information.

What makes the human brain special? That question is not easy to answer—and will occupy neuroscientists for generations to come. But a few tentative responses can already be mustered. The organ is certainly bigger than expected for our body size. And it has its own specialized areas—one of which is devoted to processing language. In recent years, brain scans have started to show that the particular way neurons connect to one another is also part of the story. A key tool in these studies is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—in particular, a version known as diffusion tensor imaging. This technique can visualize the long fibers that extend out from neurons and link brain regions without having to remove a piece of skull. Like wires, these connections carry electrical information between neurons. And the aggregate of all these links, also known as a connectome, can provide clues about how the brain processes information. W

W W

W Sanjay G. Reddy over at Reddy to Read:

Sanjay G. Reddy over at Reddy to Read: Ragnar Fjelland in Nature:

Ragnar Fjelland in Nature: