From Stanford Medicine:

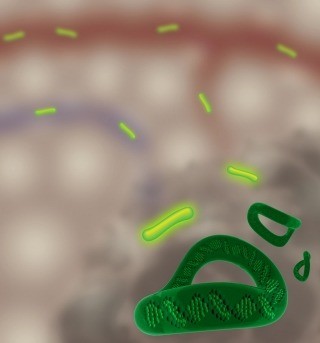

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away. Stanford University School of Medicine investigators administered a customized genetic construct consisting of tiny rings of DNA, called DNA minicircles, to mice. The scientists then showed that mice with tumors produced a substance that tumor-free mice didn’t make. The substance was easily detected 48 hours later by a simple blood test. The technique has the potential to apply to a broad range of cancers, so someday clinicians might be able not only to detect tumors, monitor the effectiveness of cancer therapies and guide the developments of anti-tumor drugs, but — importantly — to screen symptom-free populations for nascent tumors that might have otherwise gone undetected until they became larger and much tougher to treat.

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away. Stanford University School of Medicine investigators administered a customized genetic construct consisting of tiny rings of DNA, called DNA minicircles, to mice. The scientists then showed that mice with tumors produced a substance that tumor-free mice didn’t make. The substance was easily detected 48 hours later by a simple blood test. The technique has the potential to apply to a broad range of cancers, so someday clinicians might be able not only to detect tumors, monitor the effectiveness of cancer therapies and guide the developments of anti-tumor drugs, but — importantly — to screen symptom-free populations for nascent tumors that might have otherwise gone undetected until they became larger and much tougher to treat.

The hunt for cancer biomarkers — substances whose presence in an individual’s blood or urine flags a probable tumor — is nothing new, said the study’s senior author, Sanjiv “Sam” Gambhir, professor and chair of radiology and director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection. High blood levels of prostate-specific antigen, for example, can signify prostate cancer, and there are also biomarkers that sometimes signal ovarian and colorectal cancer, he said. But while various tumor types naturally secrete characteristic substances into the blood, the secreted substance is typically specific to the tumor type, with each requiring its own separate test. Complicating matters, these substances are also quite often made in healthy tissues, so a positive test result doesn’t absolutely mean a person actually has cancer. Or a tumor — especially a small one — simply may not secrete enough of the trademark substance to be detectable.

Gambhir’s team appears to have found a way to force any of numerous tumor types to produce a biomarker whose presence in the blood of mice unambiguously signifies cancer, because none of the rodents’ tissues — cancerous or otherwise — would normally be making it. This biomarker is a protein called secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase. SEAP is naturally produced in human embryos as they form and develop, but it’s not present in adults.

More here.