Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic:

When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed.

When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed.

Belleau Wood is a consequential battle in American history, and the ground on which it was fought is venerated by the Marine Corps. America and its allies stopped the German advance toward Paris there in the spring of 1918. But Trump, on that same trip, asked aides, “Who were the good guys in this war?” He also said that he didn’t understand why the United States would intervene on the side of the Allies. Trump’s understanding of concepts such as patriotism, service, and sacrifice has interested me since he expressed contempt for the war record of the late Senator John McCain, who spent more than five years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said in 2015 while running for the Republican nomination for president. “I like people who weren’t captured.”

More here.

David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including

David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including  Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.”

Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.” Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger.

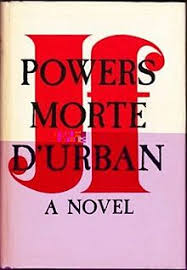

Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger. Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford.

Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford. W

W It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box.

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box. Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since

Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since  The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have

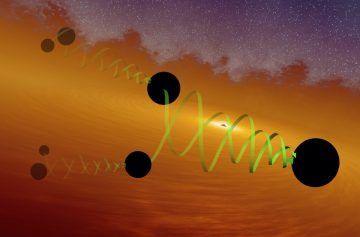

The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have  The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books.

The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books. We are living in a remarkable moment, in fact a moment unique in human history. It is a moment of confluence of severe crises, at least four, which threaten the survival of organized human life on earth, not in the distant future.

We are living in a remarkable moment, in fact a moment unique in human history. It is a moment of confluence of severe crises, at least four, which threaten the survival of organized human life on earth, not in the distant future.

As scientists edge closer to creating a vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Indian pharmaceutical companies are front and centre in the race to supply the world with an effective product. But researchers worry that, even with India’s experience as a vaccine manufacturer, its companies will struggle to produce enough doses sufficiently fast to bring its own huge outbreak under control. On top of that, it will be an immense logistical challenge to distribute the doses to people in rural and remote regions.

As scientists edge closer to creating a vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Indian pharmaceutical companies are front and centre in the race to supply the world with an effective product. But researchers worry that, even with India’s experience as a vaccine manufacturer, its companies will struggle to produce enough doses sufficiently fast to bring its own huge outbreak under control. On top of that, it will be an immense logistical challenge to distribute the doses to people in rural and remote regions.