Hari Kunzru in The New York Times:

The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was discovered and summarily executed by American Special Forces in 2011. When the narrator of Ayad Akhtar’s moving and confrontational novel “Homeland Elegies” goes there with his father in 2008 to visit relatives, he gets a lecture from his uncle about the tactical genius of 9/11, and his vision of a Muslim community based on principles espoused by the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, one that “does not bifurcate its military and political aspirations.”

The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was discovered and summarily executed by American Special Forces in 2011. When the narrator of Ayad Akhtar’s moving and confrontational novel “Homeland Elegies” goes there with his father in 2008 to visit relatives, he gets a lecture from his uncle about the tactical genius of 9/11, and his vision of a Muslim community based on principles espoused by the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, one that “does not bifurcate its military and political aspirations.”

The narrator, like Akhtar, is an American-born dramatist, whose own politics have been formed by a childhood in suburban Milwaukee and a liberal arts education. While he disagrees with his uncle, sitting in the man’s Raj-era bungalow with William Morris wallpaper, the narrator finds it easiest to listen without giving an opinion. His father, a staunch American patriot and future Trump voter, is enraged. “Trust me,” he snaps on the taxi ride home, “you don’t have a clue how terrible your life would have been if I’d stayed here.”

More here.

Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster.

Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster. Dear H,

Dear H,

Summer always seems to be the cruelest season in the Middle East. The examples include the June 1967 war, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the hijacking of Trans World Airlines Flight 847 in 1985, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and the Islamic State’s rampage through Iraq in 2014. The summer of 2020 has already joined that list. But the world should also be attuned to another possibility. Given how widespread bloodshed, despair, hunger, disease, and repression have become, a new—and far darker—chapter for the region is about to begin.

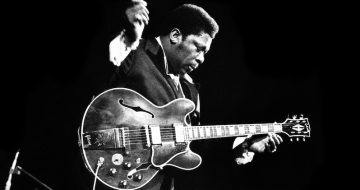

Summer always seems to be the cruelest season in the Middle East. The examples include the June 1967 war, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the hijacking of Trans World Airlines Flight 847 in 1985, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and the Islamic State’s rampage through Iraq in 2014. The summer of 2020 has already joined that list. But the world should also be attuned to another possibility. Given how widespread bloodshed, despair, hunger, disease, and repression have become, a new—and far darker—chapter for the region is about to begin. B.B. King, Indianola, Mississippi, 2013—The fat red sun settled against the horizon, throwing a last honey-sweet light across the humid evening and over a small crowd on the lawn beside a railroad track that cut through the cotton fields beyond. A quarter-moon was rising and a chorus of cicadas serenaded the imminent twilight, now joined by the sound of the band; the drummer caught the backbeat and the compere announced: “How about an Indianola hometown welcome for the one and only King of the Blues—B.B. King!”

B.B. King, Indianola, Mississippi, 2013—The fat red sun settled against the horizon, throwing a last honey-sweet light across the humid evening and over a small crowd on the lawn beside a railroad track that cut through the cotton fields beyond. A quarter-moon was rising and a chorus of cicadas serenaded the imminent twilight, now joined by the sound of the band; the drummer caught the backbeat and the compere announced: “How about an Indianola hometown welcome for the one and only King of the Blues—B.B. King!” A novel tells you far more about a writer than an essay, a poem, or even an autobiography,” says Martin Amis. He then adds, “My father thought this, too.” This statement is especially intriguing in light of his soon-to-be-published book,

A novel tells you far more about a writer than an essay, a poem, or even an autobiography,” says Martin Amis. He then adds, “My father thought this, too.” This statement is especially intriguing in light of his soon-to-be-published book,  Four days before ordering a drone strike against the Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani, Donald Trump was debating the assassination on his own Florida golf course, according to Bob Woodward’s new book on the mercurial president.

Four days before ordering a drone strike against the Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani, Donald Trump was debating the assassination on his own Florida golf course, according to Bob Woodward’s new book on the mercurial president.  When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA.

When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA. Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism.

Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism. Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year.

Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year. Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist.

Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist. Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty.

Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty. To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see

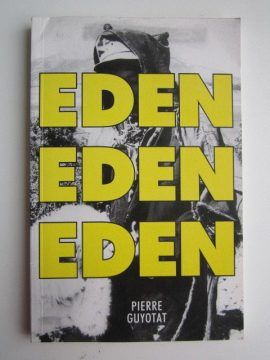

To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see  One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149).

One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149).