Christie Wilcox in Nautilus:

In their long-running effort to defeat cancer, medical researchers have made a startling discovery: A lot of the time, they have no idea how their anti-cancer drugs work. And, strange as it may sound, that is actually great news for future therapies. “We’re not saying these drugs aren’t good,” explains Ann Lin, a geneticist at Stanford University. They really do kill cancerous cells, often quite well; they just don’t do the job the way that their developers believed, she finds. Her work highlights how much of anticancer drug discovery is still based on trial-and-error searches. It’s as if your auto mechanic learned to fix your car by kicking the fenders and smacking the hood until it started. That technique might get the job done, but there would be no way to improve it or to figure out what went wrong if it failed the next time. Similarly, oncologists have often been forced to rely on drugs without a clear understanding of their mechanism of action, Lin notes; in essence, they were kicking and smacking the tumors at a molecular level.

In their long-running effort to defeat cancer, medical researchers have made a startling discovery: A lot of the time, they have no idea how their anti-cancer drugs work. And, strange as it may sound, that is actually great news for future therapies. “We’re not saying these drugs aren’t good,” explains Ann Lin, a geneticist at Stanford University. They really do kill cancerous cells, often quite well; they just don’t do the job the way that their developers believed, she finds. Her work highlights how much of anticancer drug discovery is still based on trial-and-error searches. It’s as if your auto mechanic learned to fix your car by kicking the fenders and smacking the hood until it started. That technique might get the job done, but there would be no way to improve it or to figure out what went wrong if it failed the next time. Similarly, oncologists have often been forced to rely on drugs without a clear understanding of their mechanism of action, Lin notes; in essence, they were kicking and smacking the tumors at a molecular level.

Learning what they don’t know about those drugs is a critically important step forward. It is allowing Lin and her colleagues to zero in on the actual, specific molecular mechanisms that really do kill cancerous cells. Now that those mechanisms are being identified, drug developers will be able to carry out targeted searches for other treatments that attack cancer the same way. Better yet, that’s still only half of the story. While Lin is identifying molecular mechanisms that could lead to new anticancer drugs, Todd Golub is working the problem from the other end—identifying anticancer drugs that could lead to the discovery of new mechanisms.

More here. (My note of Caution: Actually, we are not a lot better. I have been using the same two drugs to treat acute myeloid leukemia since 1977 and to this day, no one knows how they act. It is not for lack of trying or resources. This is the exact type of optimistic article that misleads the public into believing cures are around the corner.)

Columns of smoke “spread their veils / Like funeral crape upon the sylvan robe / Of thy romantic rocks, pollute thy gales, / And stain thy glassy floods”. Poet Anna Seward wrote these lines in 1785, after seeing the forges, furnaces and lime kilns of Coalbrookdale in England — the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. It is among the first descriptions of industrial emissions as ‘pollution’, a term that invoked moral impurity, the corruption of the countryside. More than two centuries later, humanity’s polluting activities have devastating impacts on biodiversity, agricultural productivity and human health. Will it take a radical reimagining of our lifestyles and sociopolitical systems to end these disastrous mistakes? Or is it already too late to avoid even greater catastrophe?

Columns of smoke “spread their veils / Like funeral crape upon the sylvan robe / Of thy romantic rocks, pollute thy gales, / And stain thy glassy floods”. Poet Anna Seward wrote these lines in 1785, after seeing the forges, furnaces and lime kilns of Coalbrookdale in England — the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. It is among the first descriptions of industrial emissions as ‘pollution’, a term that invoked moral impurity, the corruption of the countryside. More than two centuries later, humanity’s polluting activities have devastating impacts on biodiversity, agricultural productivity and human health. Will it take a radical reimagining of our lifestyles and sociopolitical systems to end these disastrous mistakes? Or is it already too late to avoid even greater catastrophe? 3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

3:16: What made you become a philosopher? Quick: Rate how much you agree with each of these items on a scale of 1 (“not me at all”) to 5 (“this is so me”):

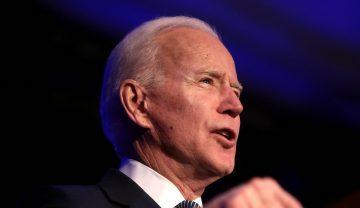

Quick: Rate how much you agree with each of these items on a scale of 1 (“not me at all”) to 5 (“this is so me”): The U.S. presidential election has so far involved and will undoubtedly continue to involve a clash over voting strategy for the left. A significant array of left commentators, for example, Cornel West, AOC, Angela Davis, and Noam Chomsky have been and will likely continue urging all progressives to vote for Biden at least in swing states, even if they can’t stand his personal history and his stated and implied policies. Another array of left commentators, for example Chris Hedges, Glenn Greenwald, Krystal Ball, and Howie Hawkins, has been and will likely continue asserting that instead all progressives should vote their true preferences, for example for the Green candidate, or not vote, but in any event not vote for someone they despise, like Joe Biden.

The U.S. presidential election has so far involved and will undoubtedly continue to involve a clash over voting strategy for the left. A significant array of left commentators, for example, Cornel West, AOC, Angela Davis, and Noam Chomsky have been and will likely continue urging all progressives to vote for Biden at least in swing states, even if they can’t stand his personal history and his stated and implied policies. Another array of left commentators, for example Chris Hedges, Glenn Greenwald, Krystal Ball, and Howie Hawkins, has been and will likely continue asserting that instead all progressives should vote their true preferences, for example for the Green candidate, or not vote, but in any event not vote for someone they despise, like Joe Biden. For decades, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has routinely warned its agents that the white supremacist and far-right militant groups it investigates often have links to law enforcement. Yet the justice department has no national strategy designed to protect the communities policed by these dangerously compromised law enforcers. As our nation grapples with how to reimagine public safety in the wake of the protests following the police killing of George Floyd, it is time to confront and resolve the persistent problem of explicit racism in law enforcement.

For decades, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has routinely warned its agents that the white supremacist and far-right militant groups it investigates often have links to law enforcement. Yet the justice department has no national strategy designed to protect the communities policed by these dangerously compromised law enforcers. As our nation grapples with how to reimagine public safety in the wake of the protests following the police killing of George Floyd, it is time to confront and resolve the persistent problem of explicit racism in law enforcement. On 13 December 1807, in fashionable Weimar, Johanna Schopenhauer picked up her pen and wrote to her 19-year-old son Arthur: ‘It is necessary for my happiness to know that you are happy, but not to be a witness to it.’ Two years earlier, in Hamburg, Johanna’s husband Heinrich Floris had been discovered dead in the canal behind their family compound. It is possible that he slipped and fell, but Arthur suspected that his father jumped out of the warehouse loft into the icy waters below. Johanna did not disagree. Four months after the suicide, she had sold the house, soon to leave for Weimar where a successful career as a writer and saloniste awaited her. Arthur stayed behind with the intention of completing the merchant apprenticeship his father had arranged shortly before his death. It wasn’t long, however, before Arthur wanted out too. In an exchange of letters throughout 1807, mother and son entered tense negotiations over the terms of Arthur’s release. Johanna would be supportive of Arthur’s decision to leave Hamburg in search of an intellectually fulfilling life – how could she not? – including using her connections to help pave the way for his university education. But on one condition: he must leave her alone. Certainly, he must not move to be near her in Weimar, and under no circumstances would she let him stay with her.

On 13 December 1807, in fashionable Weimar, Johanna Schopenhauer picked up her pen and wrote to her 19-year-old son Arthur: ‘It is necessary for my happiness to know that you are happy, but not to be a witness to it.’ Two years earlier, in Hamburg, Johanna’s husband Heinrich Floris had been discovered dead in the canal behind their family compound. It is possible that he slipped and fell, but Arthur suspected that his father jumped out of the warehouse loft into the icy waters below. Johanna did not disagree. Four months after the suicide, she had sold the house, soon to leave for Weimar where a successful career as a writer and saloniste awaited her. Arthur stayed behind with the intention of completing the merchant apprenticeship his father had arranged shortly before his death. It wasn’t long, however, before Arthur wanted out too. In an exchange of letters throughout 1807, mother and son entered tense negotiations over the terms of Arthur’s release. Johanna would be supportive of Arthur’s decision to leave Hamburg in search of an intellectually fulfilling life – how could she not? – including using her connections to help pave the way for his university education. But on one condition: he must leave her alone. Certainly, he must not move to be near her in Weimar, and under no circumstances would she let him stay with her.

In 1965, Bob Dylan gifted Allen Ginsberg with a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder, which Ginsberg was to use to record his thoughts and observations as he traveled throughout the United States. Ginsberg, already heavily influenced by Jack Kerouac’s methods of spontaneous composition, felt the taping was an ideal way to pursue his own spontaneous work. He began planning a volume of poems, a literary documentary examining contemporary America, not unlike what Kerouac had done in On the Road, or what Robert Frank had accomplished in his photographs in The Americans. He would add one important element: the violence, destruction, and inhumanity of the escalating war in Vietnam—an edgy contrast to what he was witnessing in his travels, particularly his country’s natural beauty. The public’s polarized dialogue over Vietnam—and, earlier in the decade, the civil rights movement—convinced Ginsberg that America was teetering on the precipice of a fall.

In 1965, Bob Dylan gifted Allen Ginsberg with a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder, which Ginsberg was to use to record his thoughts and observations as he traveled throughout the United States. Ginsberg, already heavily influenced by Jack Kerouac’s methods of spontaneous composition, felt the taping was an ideal way to pursue his own spontaneous work. He began planning a volume of poems, a literary documentary examining contemporary America, not unlike what Kerouac had done in On the Road, or what Robert Frank had accomplished in his photographs in The Americans. He would add one important element: the violence, destruction, and inhumanity of the escalating war in Vietnam—an edgy contrast to what he was witnessing in his travels, particularly his country’s natural beauty. The public’s polarized dialogue over Vietnam—and, earlier in the decade, the civil rights movement—convinced Ginsberg that America was teetering on the precipice of a fall. Carmen Lea Dege in Boston Review:

Carmen Lea Dege in Boston Review: Maya Adereth, Shani Cohen and Jack Gross interview Stephen Marglin in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth, Shani Cohen and Jack Gross interview Stephen Marglin in Phenomenal World: Kate Aronoff in TNR:

Kate Aronoff in TNR: Kimberly Drew and various people in the arts in Vanity Fair:

Kimberly Drew and various people in the arts in Vanity Fair: Rebecca Tan in The Washington Post:

Rebecca Tan in The Washington Post: Although Mark Twain apparently didn’t coin the phrase “truth is stranger than fiction,” he offered perhaps the best explanation for why it is so. “It is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities,” he wrote. “Truth isn’t.” History is replete with proof; try, for instance, plotting a novel that faithfully replicates the events of Sept. 11 or John F. Kennedy’s assassination and watch it be dismissed as absurd.

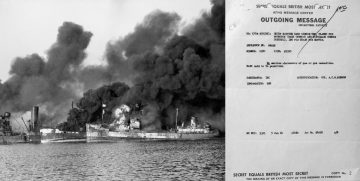

Although Mark Twain apparently didn’t coin the phrase “truth is stranger than fiction,” he offered perhaps the best explanation for why it is so. “It is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities,” he wrote. “Truth isn’t.” History is replete with proof; try, for instance, plotting a novel that faithfully replicates the events of Sept. 11 or John F. Kennedy’s assassination and watch it be dismissed as absurd.