David Mikics at Salmagundi:

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

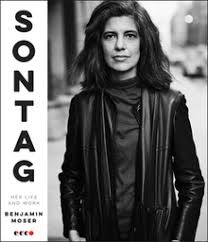

Susan Sontag was a case, all right, as Benjamin Moser’s new biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work makes clear. But she was also interesting in ways that Moser, with his taste for the tawdry and the sensational, is ill-equipped to explore.

more here.