Casey Cep in The New Yorker:

What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure.

What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure.

The Civil War features in some dozen of Faulkner’s novels. It is most prominent in those set in Yoknapatawpha County, an imaginary Mississippi landscape filled with battlefields and graveyards, veterans and widows, slaves and former slaves, draft dodgers and ghosts. In “Light in August,” the Reverend Gail Hightower is haunted by his Confederate grandfather; in “Intruder in the Dust,” the lawyer Gavin Stevens insists that all the region’s teen-age boys are obsessed with the hours before Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. In these books, no Southerner is spared the torturous influence of the war, whether he flees the region, as Quentin Compson does, in “The Sound and the Fury,” or whether, like Rosa Coldfield, in “Absalom, Absalom!,” she stays.

A new book by Michael Gorra, “The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War” (Liveright), traces Faulkner’s literary depictions of the military conflict in the nineteenth century and his personal engagement with the racial conflict of the twentieth. The latter struggle, within the novelist himself, is the real war of Gorra’s subtitle. In “The Saddest Words,” Faulkner emerges as a character as tragic as any he invented: a writer who brilliantly portrayed the way that the South’s refusal to accept its defeat led to cultural decay, but a Southerner whose private letters and public statements were riddled with the very racism that his books so pointedly damned.

More here.

The beating heart of literature is writers’ engagement with sadness and the conflicts of their time. Many of these conflicts are centred on wealth and access to natural resources: land, water, mineral, forest, stone, sand, clean air. Big money, often with the aid of big media, attempts to shape public opinion about who controls the world, who deserves what, how resources ought to be shared. In a similar vein, traditional hegemonies in India – patriarchy and the caste system – try to control the stories we tell about each other.

The beating heart of literature is writers’ engagement with sadness and the conflicts of their time. Many of these conflicts are centred on wealth and access to natural resources: land, water, mineral, forest, stone, sand, clean air. Big money, often with the aid of big media, attempts to shape public opinion about who controls the world, who deserves what, how resources ought to be shared. In a similar vein, traditional hegemonies in India – patriarchy and the caste system – try to control the stories we tell about each other.

THERE’S A WEALTH OF

THERE’S A WEALTH OF The Covid-19 pandemic has made the world feel lonelier than ever as people have been shut away in their homes, aching to gather with their loved ones again. This instinct to evade loneliness is deeply engrained in our brains, and a new study published in the journal

The Covid-19 pandemic has made the world feel lonelier than ever as people have been shut away in their homes, aching to gather with their loved ones again. This instinct to evade loneliness is deeply engrained in our brains, and a new study published in the journal

More than 40 years ago, three psychologists published

More than 40 years ago, three psychologists published  Thea Riofrancos in The Baffler:

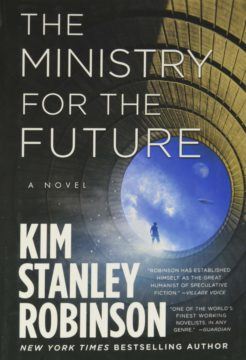

Thea Riofrancos in The Baffler: Gerry Canavan in the LA Review of Books:

Gerry Canavan in the LA Review of Books:

Suzanne Schneider in n+1:

Suzanne Schneider in n+1: Nicola Miller in Boston Review:

Nicola Miller in Boston Review: Gray never bought the idea that his book was a handbook for despair. His subject was humility; his target any ideology that believed it possessed anything more than doubtful and piecemeal answers to vast and changing questions. The cat book is written in that spirit. If like me you read with a pencil to hand, you will be underlining constantly with a mix of purring enjoyment and frequent exclamation marks. “Consciousness has been overrated,” Gray will write, coolly. Or “the flaw in rationalism is the belief that human beings can live by applying a theory”. Or “human beings quickly lose their humanity but cats never stop being cats”. He concludes with a 10-point list of how cats might give their anxious, unhappy, self-conscious human companions hints “to live less awkwardly”. These range from “never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable”, to “do not look for meaning in your suffering” to “sleep for the joy of sleeping”.

Gray never bought the idea that his book was a handbook for despair. His subject was humility; his target any ideology that believed it possessed anything more than doubtful and piecemeal answers to vast and changing questions. The cat book is written in that spirit. If like me you read with a pencil to hand, you will be underlining constantly with a mix of purring enjoyment and frequent exclamation marks. “Consciousness has been overrated,” Gray will write, coolly. Or “the flaw in rationalism is the belief that human beings can live by applying a theory”. Or “human beings quickly lose their humanity but cats never stop being cats”. He concludes with a 10-point list of how cats might give their anxious, unhappy, self-conscious human companions hints “to live less awkwardly”. These range from “never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable”, to “do not look for meaning in your suffering” to “sleep for the joy of sleeping”. To write as an ironist, especially today, is to risk that the reader loses patience with hedging, backtracking, spirals of cleverness. But sometimes the layers of the onion ensure the purity of the tears. “That Was Now, This Is Then” is anchored by “Collins Ferry Landing,” an elegy for the poet’s father. Its middle section, in prose, begins by addressing Seshadri’s father in the self-amused voice that is typical for this writer: “I have a friend. (You’ll be glad to know.) She and I work together. (You’ll be glad to know I still have a job.) She’s an ally. She’s sympathetic.” But it turns out that this sympathetic ally has done something terrible. The poet had been speaking about his loss (“I was telling her about you”) and then shied away from it into a galaxy of other subjects (“I was describing cultures of shame evolving across millennia; economies of scarcity versus economies of surplus. … Deep India, strewn with elephants and cobras”). And then the woman does this: “She put her right hand on my left arm and said, ‘He’ll always be with you. In your heart.’”

To write as an ironist, especially today, is to risk that the reader loses patience with hedging, backtracking, spirals of cleverness. But sometimes the layers of the onion ensure the purity of the tears. “That Was Now, This Is Then” is anchored by “Collins Ferry Landing,” an elegy for the poet’s father. Its middle section, in prose, begins by addressing Seshadri’s father in the self-amused voice that is typical for this writer: “I have a friend. (You’ll be glad to know.) She and I work together. (You’ll be glad to know I still have a job.) She’s an ally. She’s sympathetic.” But it turns out that this sympathetic ally has done something terrible. The poet had been speaking about his loss (“I was telling her about you”) and then shied away from it into a galaxy of other subjects (“I was describing cultures of shame evolving across millennia; economies of scarcity versus economies of surplus. … Deep India, strewn with elephants and cobras”). And then the woman does this: “She put her right hand on my left arm and said, ‘He’ll always be with you. In your heart.’” Susan Simien was born and raised in San Francisco, but he had begun to feel like a stranger in his hometown. In the Nineties, when Simien was growing up, the Ingleside neighborhood where he lived was diverse—nearly half of its households were, like Simien’s, middle-class and African-American. But in recent years, friends and neighbors had left for more affordable towns and suburbs—so many that Simien had lost track. Over the course of his lifetime, the African-American population in San Francisco had been cut in half. “You can’t throw a rock and hit someone who actually grew up around here,” Simien liked to say.

Susan Simien was born and raised in San Francisco, but he had begun to feel like a stranger in his hometown. In the Nineties, when Simien was growing up, the Ingleside neighborhood where he lived was diverse—nearly half of its households were, like Simien’s, middle-class and African-American. But in recent years, friends and neighbors had left for more affordable towns and suburbs—so many that Simien had lost track. Over the course of his lifetime, the African-American population in San Francisco had been cut in half. “You can’t throw a rock and hit someone who actually grew up around here,” Simien liked to say. What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure.

What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure. I asked Iva and James to tell me everything they knew. They looked uncomfortable, whispering despite the fact that there wasn’t really anyone there but the barista.

I asked Iva and James to tell me everything they knew. They looked uncomfortable, whispering despite the fact that there wasn’t really anyone there but the barista.