Revisions

Before the poet was a poet

nothing was reworked:

not the smudge of ink on twelve sets of clothes

not the fearsome top berth on the train

not a room full of boxes and dull windows

not the cat that left its kittens and afterbirth in a pair of jeans

not doubt.

Before the poet was a poet

everything had a place:

six years were six years parallel lines followed rules

like obedient children

[the Dewey Decimal System]

………………………………………………….. homes remained where they’d

been left.

Before the poet was a poet

many things went unseen:

clouds sometimes wheedled a ray out of the sun| parents kept photos under their

pillows| letters never said everything they wanted to| lectures were interrupted by a

commotion of leaves | | every step was upon a blind spot.

by Sridala Swami

from Escape Artist

Aleph Book Co., New Delhi, 2014

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges.

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges. We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as

We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as  We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control.

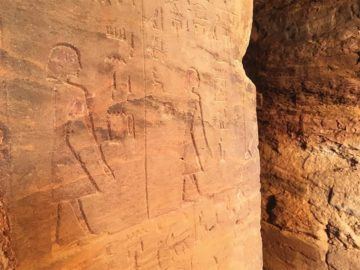

We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control. Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet.

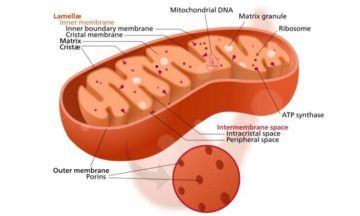

Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet. Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of

Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of  The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be.

The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be. In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote.

In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote. Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book,

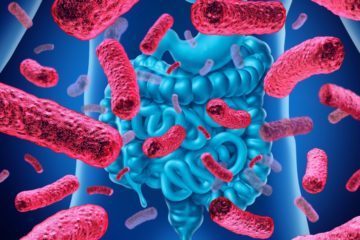

Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book,  We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974).

We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974). When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in

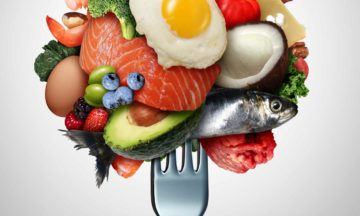

When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in  The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight.

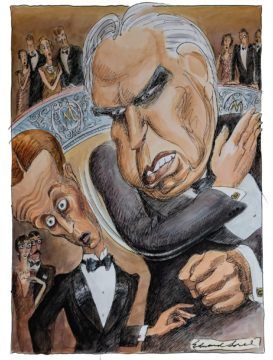

The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight. Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his.

Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his.