Eloghosa Osunde in The Paris Review:

My memory of my childhood is a black hole, save for the moments and ages marked by revelations and miracles. Take age six for instance, the year I learned to call things that are not (yet) as though they are (already.) It’s a biblical lesson, this, and my brothers were born from inside it, after years of waiting. Leaning on those words from the mouth of my mother, I prayed nightly for twin siblings, and soon started to talk about them like I knew them already. In a sense, I did. One, because they were real before their bodies were formed, and two, because my requests were already cool wax on the inside of God’s ear. I was taught things about holding hope unswervingly, about manifesting with laser focus, and the veracity of those lessons raised the hairs on the back of my neck even when there was no one there. I sealed prayers with amens and had them delivered swiftly; fleshed wishes out in my heart that stumbled into my life, already breathing. The pattern begins in my first name, directly translated to mean “it is not hard for God to do.” As in, nothing is. That name leads my head. My family took my dreams seriously, because God put the future behind my eyes often, but when the seeing got too heavy, I gave one of my many eyes back to God—the one that got visions, that put the weight of knowing on me—saying, This one is too much. Age thirteen, I believe, the year I learned that God understands consent, that They will never force anything on me for the sake of it.

The spiritual controls the physical, so everything breathes there before it ever lands here. I’ve never lost this lesson, which is also an inheritance, as in drooling through the genetic code. A gift, as in given freely. I did hide it though, so as not to look unhinged. For a long time, there was nothing I wanted more than to be normal, to be as a person should, to be young, to unknow things. It still takes work to release the weight of normal, of should.

More here.

In May of this year, The Washington Post published an article damningly titled “Millennials are the Unluckiest Generation in U.S. History.” The piece seemed to tell a truth that our cohort knows all too well: that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought not just an economic recession, but a regression. There were as many jobs in the spring of 2020 as there were in the fall of 1999. For those of us born between the years of 1981 and 1996, it is as if the post-crisis “growth” of the past 10 years never even happened.

In May of this year, The Washington Post published an article damningly titled “Millennials are the Unluckiest Generation in U.S. History.” The piece seemed to tell a truth that our cohort knows all too well: that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought not just an economic recession, but a regression. There were as many jobs in the spring of 2020 as there were in the fall of 1999. For those of us born between the years of 1981 and 1996, it is as if the post-crisis “growth” of the past 10 years never even happened. As the United States and much of the rest of the world struggles through a winter of intensifying death and disease, it is worth remembering that beyond the present darkness lies the dawn, as newly approved vaccines become widely available, and with that, perhaps, a return to something resembling normalcy.

As the United States and much of the rest of the world struggles through a winter of intensifying death and disease, it is worth remembering that beyond the present darkness lies the dawn, as newly approved vaccines become widely available, and with that, perhaps, a return to something resembling normalcy. The Founding Fathers are a perennial source of both wisdom and controversy. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has taken pride of place in these public debates in recent years, thanks in part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical and Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography. In this interview, Michael Busch speaks with journalist and economist Christian Parenti about his new book

The Founding Fathers are a perennial source of both wisdom and controversy. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has taken pride of place in these public debates in recent years, thanks in part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical and Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography. In this interview, Michael Busch speaks with journalist and economist Christian Parenti about his new book  Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth. Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a

Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a  It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me.

It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me. This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’.

This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’. Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself.

Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself. On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat.

On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat. The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships.

The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships. Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

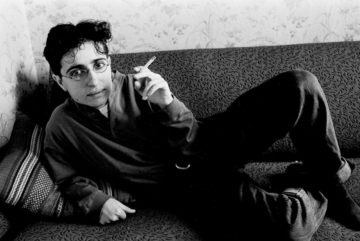

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate. In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.