Lydia Wilson in Smithsonian:

Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet.

Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet.

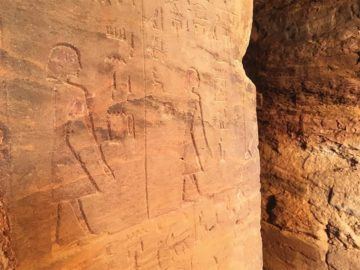

The evidence, which continues to be examined and reinterpreted 116 years after its discovery, is on a windswept plateau in Egypt called Serabit el-Khadim, a remote spot even by Sinai standards. Yet it wasn’t too difficult for even ancient Egyptians to reach, as the presence of a temple right at the top shows. When I visited in 2019, I looked out over the desolate, beautiful landscape from the summit and realized I was seeing the same view the inventors of the alphabet had seen every day. The temple is built into the living rock, dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of turquoise (among many other things); stelae chiseled with hieroglyphs line the paths to the shrine, where archaeological evidence indicates there was once an extensive temple complex. A mile or so southwest of the temple is the source of all ancient interest in this area: embedded in the rock are nodules of turquoise, a stone that symbolized rebirth, a vital motif in Egyptian culture and the color that decorated the walls of their lavish tombs. Turquoise is why Egyptian elites sent expeditions from the mainland here, a project that began around 2,800 B.C. and lasted for over a thousand years. Expeditions made offerings to Hathor in hopes of a rich haul to take home.

More here.