Katharine Sanderson in Nature:

Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy1.

Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy1.

Physicians wanted to know whether the device could be customized to spot symptoms of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The short answer was ‘yes’. Some 400 of the devices are now being used in Chicago, Illinois, to help spot early signs of COVID-19 in front-line health workers, as well as for disease monitoring in patients. His team has further tweaked the design to assess how coughing rates change in people with COVID-19. “Several of us, designated as essential workers due to our COVID device work, have been in the lab on a daily basis throughout this period,” Rogers says. “I have not missed a day.” His team members also wear the devices in the lab, to monitor themselves for the onset of symptoms. “So far, nothing,” he says.

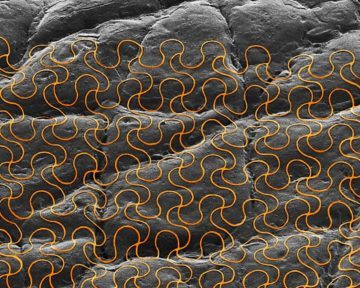

Rogers is one of the most prolific researchers of wearable skin-inspired electronics worldwide. This ‘e-skin’ technology has already made it into volunteers and clinics globally, helping to monitor vital signs in premature infants and hydration in athletes, for instance. Other e-skins are giving robots a lighter, human-like touch. But whether they are for people or robots, such devices represent a significant chemical and engineering challenge: electronic components are typically brittle and inflexible, and human skin is a malleable but difficult canvas.

More here.