David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review:

David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review:

DB: One of the topics you discuss in the book [Consequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and Resistance, coauthored with Marv Waterstone] is the connection between David Hume, the eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosopher, and Antonio Gramsci, the noted twentieth-century Marxist thinker. What’s that connection?

NC: Hume was a great philosopher. He wrote an important essay, “Of the First Principles of Government” (1741), one of the classic texts on what we now call political philosophy or political science. He opens his study by raising a question. He’s surprised, he says, to see the “easiness” with which people subordinate themselves to power systems. That’s a mystery, because the people themselves really have the power. Why do they subject themselves to masters? The answer, he says, must be consent: the masters succeed in what we now call manufacturing consent. They keep the public in line by their belief that they must subordinate themselves to power systems. And he says this miracle occurs in all societies, no matter how brutal or how free.

Hume was writing in the wake of the first democratic revolution, the English revolution of the mid-seventeenth century, which led to what we call the British constitution—basically, that the king will be subordinate to parliament. Parliament at that time basically meant merchants and manufacturers. Hume’s close friend, Adam Smith, wrote about the consequences of the revolution. In his own famous book The Wealth of Nations (1776), he pointed out that the now sovereign “merchants and manufacturers” are the true “masters of mankind.” They used their power to control the government and to ensure that their own interests are very well taken care of, no matter how “grievous” the effect on the people of England—and even worse, on those who are subject to what he called “the savage injustice of the Europeans,” referring mainly to the British rule in India.

More here.

If power were

If power were  Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny.

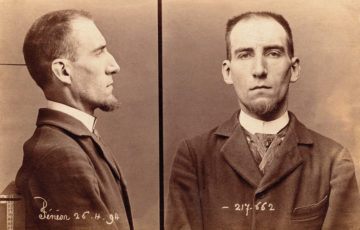

Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny. The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.”

The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.” Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics.

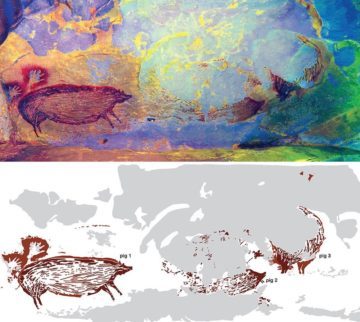

Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics. The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

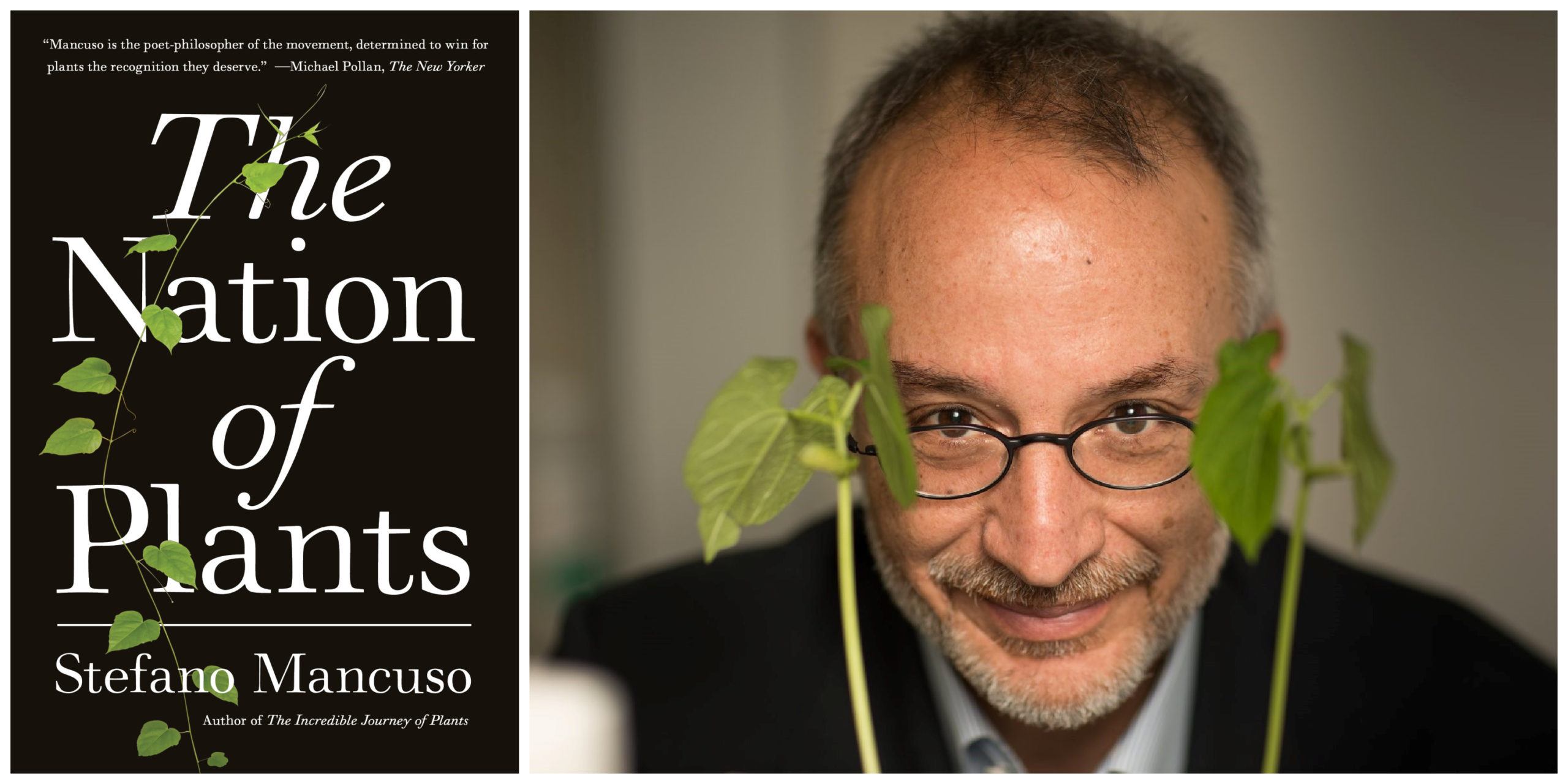

The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time. Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on.

Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on. Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of

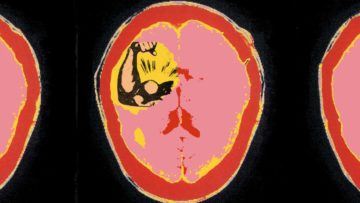

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of  In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique.

In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique. Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it.

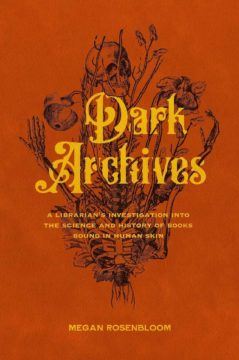

Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it. WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why?

WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why?