Shi En Kim in Smithsonian:

More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.”

More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.”

Turner had an inkling of what the textured surfaces could represent. But as an early-career academic then, she withheld her findings so as not to cause a stir. After several return trips and a slew of publications by other researchers earlier this year on similar-looking fossils, Turner, now a field geologist at Laurentian University, is finally ready to step forward with her discovery: The spangled stones she found are sponge fossils dated at 890 million years old, placing sponges as the earliest prehistoric animal that humanity has ever found so far. Published today in the journal Nature, her findings suggest that animals popped up long before Earth was considered hospitable enough to support complex life. “It’s a big step forward,” says Joachim Reitner, a geobiologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany who wasn’t involved in the study. Like Turner, he’s convinced that the fossils are sponges, because the complexity of the craggy curlicues rules out all other bacterial or fungal candidates. “We have no other choices,” he says.

“T

“T I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored.

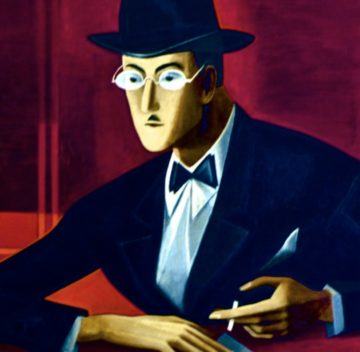

I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored. When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour. Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for

Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for  Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College.

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. P

P Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain.

Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain. Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators

Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators  Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has

Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has  Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.”

Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.” It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider.

It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider. Time after time, Segnit meets the most skilled practitioners, the most enlightened minds on the planet, and time after time they fail to find the words. Early on we are introduced to Sister Nectaria, an elderly nun who has lived at a remote monastery on a Greek island since the age of eleven. She is, says Segnit, ‘a living, breathing, invocation of god’. But she finds his questions irritating, or invasive, or beside the point. Later, we meet Tenzin Palmo, a British woman formerly known as Diane Perry who spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. ‘I hardly remember any of it,’ she insists. ‘At the time it seemed very ordinary.’

Time after time, Segnit meets the most skilled practitioners, the most enlightened minds on the planet, and time after time they fail to find the words. Early on we are introduced to Sister Nectaria, an elderly nun who has lived at a remote monastery on a Greek island since the age of eleven. She is, says Segnit, ‘a living, breathing, invocation of god’. But she finds his questions irritating, or invasive, or beside the point. Later, we meet Tenzin Palmo, a British woman formerly known as Diane Perry who spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. ‘I hardly remember any of it,’ she insists. ‘At the time it seemed very ordinary.’