Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

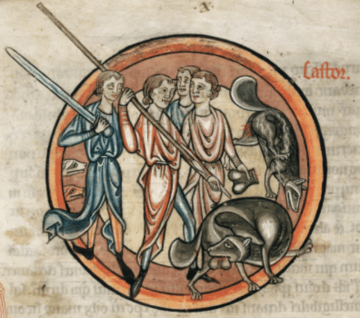

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “Wynona’s Big Brown Beaver” (1995), that entirely explains this animal’s peculiar symbolic scent. The crude term for a woman’s genitals, “beaver”, itself builds on a long history in which the figure of the animal is held up as a mirror and a speculum of human venery, and also of the transcendence of this condition through virtue.

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “Wynona’s Big Brown Beaver” (1995), that entirely explains this animal’s peculiar symbolic scent. The crude term for a woman’s genitals, “beaver”, itself builds on a long history in which the figure of the animal is held up as a mirror and a speculum of human venery, and also of the transcendence of this condition through virtue.

For most of its history the beaver, hunted for its medicinal castoreum, was sooner associated with male testicles, and with the horrible yet paradoxically emboldening prospect of their loss. Later, it was taken up as the very model of the social animal, living in imagined New World dam communities constructed through the ingenious collaborative labor of these hominoid rodents. Beavers, the “busy” American animals, embodied the work ethic so many thought necessary for the transformation of that wild continent.

It is worth considering the extent to which these two images of the beaver —the one focused on its hind parts and their perceived virtues and vices, the other on its industry— are but two chapters of a single continuous history.

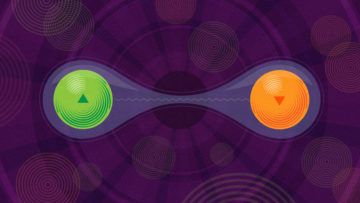

We take for granted that an event in one part of the world cannot instantly affect what happens far away. This principle, which physicists call locality, was long regarded as a bedrock assumption about the laws of physics. So when Albert Einstein and two colleagues showed in 1935 that quantum mechanics permits “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein put it, this feature of the theory seemed highly suspect. Physicists wondered whether quantum mechanics was missing something.

We take for granted that an event in one part of the world cannot instantly affect what happens far away. This principle, which physicists call locality, was long regarded as a bedrock assumption about the laws of physics. So when Albert Einstein and two colleagues showed in 1935 that quantum mechanics permits “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein put it, this feature of the theory seemed highly suspect. Physicists wondered whether quantum mechanics was missing something. It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has

It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has  So here is my ask. I want fiction by “men” in which they go into real detail about the internal mechanics of their own masculinity. I want evidence of that interiority on the page. Does it exist. All I’ve ever seen is silence or violence. I mean he’s perpetually doing it, the performance of being a man in writing, but he concomitantly refuses its existence except when there’s a glitch, meaning a woman, a queer, or an oddly behaving man. It’s like the only way a man ever talks about gender at all is by talking about them. Never talking about how it is to be a man.

So here is my ask. I want fiction by “men” in which they go into real detail about the internal mechanics of their own masculinity. I want evidence of that interiority on the page. Does it exist. All I’ve ever seen is silence or violence. I mean he’s perpetually doing it, the performance of being a man in writing, but he concomitantly refuses its existence except when there’s a glitch, meaning a woman, a queer, or an oddly behaving man. It’s like the only way a man ever talks about gender at all is by talking about them. Never talking about how it is to be a man. TM: The epigraph to your poem “Cotton Candy” is from John Donne: “To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us.” In its original context, the line appears: “All their proportion’s lame, it sinks, it swells; / For of meridians and parallels / Man hath weaved out a net, and this net thrown / Upon the heavens, and now they are his own. / Loth to go up the hill, or labour thus / To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us. / We spur, we rein the stars, and in their race / They’re diversely content to obey our pace.” I love your epigraphic eye here. Who is Donne to you, as both poet and legacy? Why choose these lines in particular from his poem?

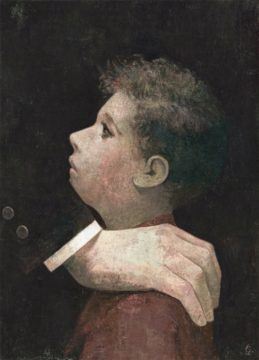

TM: The epigraph to your poem “Cotton Candy” is from John Donne: “To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us.” In its original context, the line appears: “All their proportion’s lame, it sinks, it swells; / For of meridians and parallels / Man hath weaved out a net, and this net thrown / Upon the heavens, and now they are his own. / Loth to go up the hill, or labour thus / To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us. / We spur, we rein the stars, and in their race / They’re diversely content to obey our pace.” I love your epigraphic eye here. Who is Donne to you, as both poet and legacy? Why choose these lines in particular from his poem? In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.”

In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.” Blaise Pascal was a renowned French polymath of the 17th century, scientist, philosopher, mathematician, inventor, and later in life a theologian. Among his many contributions was an attempt to prove by logical means the existence of God, which came to be known as Pascal’s Wager. Stated simply, Pascal reasoned that not believing in God, if there was one, would damn you to eternal suffering. Conversely, believing in God, if there wasn’t one, would cost you little in this life and nothing once you were dead. Therefore, the only sensible course of action was to believe in God.

Blaise Pascal was a renowned French polymath of the 17th century, scientist, philosopher, mathematician, inventor, and later in life a theologian. Among his many contributions was an attempt to prove by logical means the existence of God, which came to be known as Pascal’s Wager. Stated simply, Pascal reasoned that not believing in God, if there was one, would damn you to eternal suffering. Conversely, believing in God, if there wasn’t one, would cost you little in this life and nothing once you were dead. Therefore, the only sensible course of action was to believe in God. “It feels qualitatively different this time.” There are few people I know in South Africa who don’t think this about the

“It feels qualitatively different this time.” There are few people I know in South Africa who don’t think this about the  How can data be biased? Isn’t it supposed to be an objective reflection of the real world? We all know that these are somewhat naive rhetorical questions, since data can easily inherit bias from the people who collect and analyze it, just as an algorithm can make biased suggestions if it’s trained on biased datasets. A better question is, how do biases creep in, and what can we do about them? Catherine D’Ignazio is an MIT professor who has studied how biases creep into our data and algorithms, and even into the expression of values that purport to protect objective analysis. We discuss examples of these processes and how to use data to make things better.

How can data be biased? Isn’t it supposed to be an objective reflection of the real world? We all know that these are somewhat naive rhetorical questions, since data can easily inherit bias from the people who collect and analyze it, just as an algorithm can make biased suggestions if it’s trained on biased datasets. A better question is, how do biases creep in, and what can we do about them? Catherine D’Ignazio is an MIT professor who has studied how biases creep into our data and algorithms, and even into the expression of values that purport to protect objective analysis. We discuss examples of these processes and how to use data to make things better. Human rights activists, journalists and lawyers across the world have been targeted by authoritarian governments using hacking software sold by the Israeli surveillance company NSO Group, according to an investigation into a massive data leak.

Human rights activists, journalists and lawyers across the world have been targeted by authoritarian governments using hacking software sold by the Israeli surveillance company NSO Group, according to an investigation into a massive data leak. Byung-Chul Han tells us in The Disappearance of Rituals, that ‘symbolic perception, as recognition, is the perception of the permanent’. In a world that often seems to be determined by change, by transient experiences, names are an anomaly. They are stubborn things, pushing back against the relentless march of time. Ages change, job titles, citizenship, but names we carry with us. In defiance of a life in constant motion. When we name newborns, we are trying to locate them in the world by carving out their distinction from others, as absolute immutable entities. Some part of that distinction will follow them through the trajectory of their life. Names endure, names remain.

Byung-Chul Han tells us in The Disappearance of Rituals, that ‘symbolic perception, as recognition, is the perception of the permanent’. In a world that often seems to be determined by change, by transient experiences, names are an anomaly. They are stubborn things, pushing back against the relentless march of time. Ages change, job titles, citizenship, but names we carry with us. In defiance of a life in constant motion. When we name newborns, we are trying to locate them in the world by carving out their distinction from others, as absolute immutable entities. Some part of that distinction will follow them through the trajectory of their life. Names endure, names remain. I’d like to set up an experiment to chart the sadness—try to find out where it comes from, where it goes—to trace it, in that melody (whichever variation) as it threads across Manhattan from the Lower East Side straight across the river, more or less west, into the suburbs of New Jersey and whatever lies beyond. This would require, I’m guessing, maybe a hundred saxophonists stationed along the route on tops of buildings, water towers, farther out on people’s porches (with permission), empty parking lots, at intervals determined by the limits of their mutual audibility under variable conditions in the middle of the night, so each would strain a bit to pick it up and pass it on in step until they’re going all at once and all strung out along this fraying thread of melody for hours, with relievers in reserve. There’s bound to be some drifting in and out of phase, attenuation of the tempo, of the sadness for that matter, of the waveform, what I think of as the waveform of the whole thing as it comes across the river losing amplitude and sharpness, rounding, flattening, and diffusing into neighborhoods where maybe it just sort of washes over people staying up to hear it or, awakened, wondering what is that out there so faint and faintly echoed, faintly sad but not so sad that you can’t close your eyes again and drift right back to sleep.

I’d like to set up an experiment to chart the sadness—try to find out where it comes from, where it goes—to trace it, in that melody (whichever variation) as it threads across Manhattan from the Lower East Side straight across the river, more or less west, into the suburbs of New Jersey and whatever lies beyond. This would require, I’m guessing, maybe a hundred saxophonists stationed along the route on tops of buildings, water towers, farther out on people’s porches (with permission), empty parking lots, at intervals determined by the limits of their mutual audibility under variable conditions in the middle of the night, so each would strain a bit to pick it up and pass it on in step until they’re going all at once and all strung out along this fraying thread of melody for hours, with relievers in reserve. There’s bound to be some drifting in and out of phase, attenuation of the tempo, of the sadness for that matter, of the waveform, what I think of as the waveform of the whole thing as it comes across the river losing amplitude and sharpness, rounding, flattening, and diffusing into neighborhoods where maybe it just sort of washes over people staying up to hear it or, awakened, wondering what is that out there so faint and faintly echoed, faintly sad but not so sad that you can’t close your eyes again and drift right back to sleep. Memoria is a beautiful and mysterious movie, slow cinema that decelerates your heartbeat.

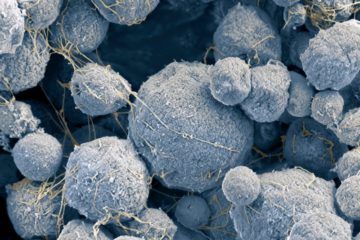

Memoria is a beautiful and mysterious movie, slow cinema that decelerates your heartbeat.  The Borg have landed — or, at least, researchers have discovered their counterparts here on Earth. Scientists analysing samples from muddy sites in the western United States have found novel DNA structures that seem to scavenge and ‘assimilate’ genes from microorganisms in their environment, much like the fictional Star Trek ‘Borg’ aliens who assimilate the knowledge and technology of other species. These extra-long DNA strands, which the scientists named in honour of the aliens, join a diverse collection of genetic structures — circular plasmids, for example — known as extrachromosomal elements (ECEs). Most microbes have one or two chromosomes that encode their primary genetic blueprint. But they can host, and often share between them, many distinct ECEs. These carry non-essential but useful genes, such as those for antibiotic resistance.

The Borg have landed — or, at least, researchers have discovered their counterparts here on Earth. Scientists analysing samples from muddy sites in the western United States have found novel DNA structures that seem to scavenge and ‘assimilate’ genes from microorganisms in their environment, much like the fictional Star Trek ‘Borg’ aliens who assimilate the knowledge and technology of other species. These extra-long DNA strands, which the scientists named in honour of the aliens, join a diverse collection of genetic structures — circular plasmids, for example — known as extrachromosomal elements (ECEs). Most microbes have one or two chromosomes that encode their primary genetic blueprint. But they can host, and often share between them, many distinct ECEs. These carry non-essential but useful genes, such as those for antibiotic resistance. One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.”

One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.”