Carrie Battan at The New Yorker:

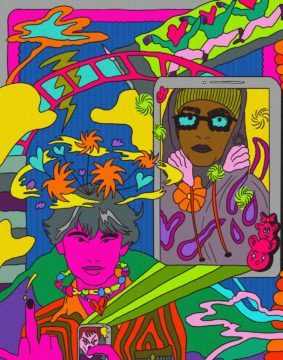

In 2014, music fans and critics began paying close attention to a mysterious group of artists who’d started releasing tracks online. They were part of PC Music, a loose electronic-music collective that functioned more like a conceptual-art project. Led by a young, inventive producer from London named A. G. Cook, PC Music, and its affiliates, rejected a dark, murky strain of underground electronic music that was beloved at the time. Instead, they latched onto the most exuberant and absurd elements of pop, making cutesy, theatrical songs that sounded a bit like children’s music, but with an unsettling aftertaste. If mainstream pop is designed to make people feel as if they’re on common ground with all of humanity, this music made listeners feel like they were in on a very specific joke. In a Pitchfork article titled “PC Music’s Twisted Electronic Pop: A User’s Manual,” one critic wrote, “The shadowy operation and its bewildering brand of hyper-pop have been everywhere in the past few months . . . and its influence seems to be growing on a daily basis.”

In 2014, music fans and critics began paying close attention to a mysterious group of artists who’d started releasing tracks online. They were part of PC Music, a loose electronic-music collective that functioned more like a conceptual-art project. Led by a young, inventive producer from London named A. G. Cook, PC Music, and its affiliates, rejected a dark, murky strain of underground electronic music that was beloved at the time. Instead, they latched onto the most exuberant and absurd elements of pop, making cutesy, theatrical songs that sounded a bit like children’s music, but with an unsettling aftertaste. If mainstream pop is designed to make people feel as if they’re on common ground with all of humanity, this music made listeners feel like they were in on a very specific joke. In a Pitchfork article titled “PC Music’s Twisted Electronic Pop: A User’s Manual,” one critic wrote, “The shadowy operation and its bewildering brand of hyper-pop have been everywhere in the past few months . . . and its influence seems to be growing on a daily basis.”

more here.

E

E In the darkness of her small bedroom in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas, Sara Qquehuarucho Zamalloa packed her bag, thoughts racing: Would the weather be good? Would the team be friendly? Would she encounter park rangers with bad attitudes toward women? Would her mum, who suffers from chronic pain, be okay while she was gone?

In the darkness of her small bedroom in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas, Sara Qquehuarucho Zamalloa packed her bag, thoughts racing: Would the weather be good? Would the team be friendly? Would she encounter park rangers with bad attitudes toward women? Would her mum, who suffers from chronic pain, be okay while she was gone? The class structure of Western society has gotten scrambled over the past few decades. It used to be straightforward: You had the rich, who joined country clubs and voted Republican; the working class, who toiled in the factories and voted Democratic; and, in between, the mass suburban middle class. We had a clear idea of what class conflict, when it came, would look like—members of the working classes would align with progressive intellectuals to take on the capitalist elite.

The class structure of Western society has gotten scrambled over the past few decades. It used to be straightforward: You had the rich, who joined country clubs and voted Republican; the working class, who toiled in the factories and voted Democratic; and, in between, the mass suburban middle class. We had a clear idea of what class conflict, when it came, would look like—members of the working classes would align with progressive intellectuals to take on the capitalist elite. By the summer of 1981, I had completed my PhD under Steve’s supervision and was starting a junior faculty position at Harvard. I knew that my parents, who were visiting, would enjoy meeting Steve and Louise, so we all had dinner together in my backyard. Realizing how much it would please my parents, Steve made some kind remarks about me during dinner. But the most memorable moment was when we were discussing how to make ice cream, and Steve expressed puzzlement over why one adds salt to the ice-cream maker. My Dad, who was not a scientist, helpfully suggested, “Isn’t it to lower the melting point of the ice, so the ice cream will be cold enough to solidify?” “Of course!” Steve replied, slapping his forehead. “I never understood that before. Thank you!” And for the rest of his life, my Dad would relish the time he gave the great Steven Weinberg a physics lesson.

By the summer of 1981, I had completed my PhD under Steve’s supervision and was starting a junior faculty position at Harvard. I knew that my parents, who were visiting, would enjoy meeting Steve and Louise, so we all had dinner together in my backyard. Realizing how much it would please my parents, Steve made some kind remarks about me during dinner. But the most memorable moment was when we were discussing how to make ice cream, and Steve expressed puzzlement over why one adds salt to the ice-cream maker. My Dad, who was not a scientist, helpfully suggested, “Isn’t it to lower the melting point of the ice, so the ice cream will be cold enough to solidify?” “Of course!” Steve replied, slapping his forehead. “I never understood that before. Thank you!” And for the rest of his life, my Dad would relish the time he gave the great Steven Weinberg a physics lesson. 100 years ago yesterday — on July 29, 1921 — Adolph Hitler was elected leader of the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party, later known as the Nazi Party. The combustible Army corporal succeeded the party’s original leader, Anton Drexler, whom Hitler originally been sent to spy on, but whose ideas he came to admire (he may even have shaved his mustache to emulate his predecessor). The 533-1 delegate vote set in motion a series of events that would dominate the next two and a half decades of world history.

100 years ago yesterday — on July 29, 1921 — Adolph Hitler was elected leader of the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party, later known as the Nazi Party. The combustible Army corporal succeeded the party’s original leader, Anton Drexler, whom Hitler originally been sent to spy on, but whose ideas he came to admire (he may even have shaved his mustache to emulate his predecessor). The 533-1 delegate vote set in motion a series of events that would dominate the next two and a half decades of world history. W

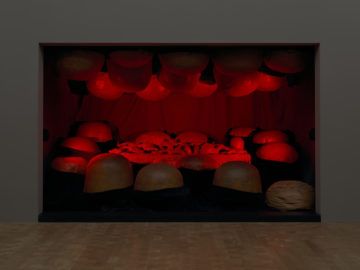

W The list of mycologists whose names are known beyond their fungal field is short, and at its apex is Paul Stamets. Educated in, and a longtime resident of, the mossy, moldy, mushy Pacific Northwest region, Stamets has made numerous contributions over the past several decades— perhaps the best summation of which can be found in his 2005 book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. But now he is looking beyond Earth to discover new ways that mushrooms can help with the exploration of space.

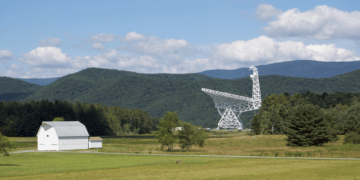

The list of mycologists whose names are known beyond their fungal field is short, and at its apex is Paul Stamets. Educated in, and a longtime resident of, the mossy, moldy, mushy Pacific Northwest region, Stamets has made numerous contributions over the past several decades— perhaps the best summation of which can be found in his 2005 book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. But now he is looking beyond Earth to discover new ways that mushrooms can help with the exploration of space. The Log Lady of the Quiet Zone lived a few miles away and had the mysterious power to “detect” WiFi, cell signals, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. I was told I might find the Log Lady at church—perhaps the only church in America quiet enough for her to attend.

The Log Lady of the Quiet Zone lived a few miles away and had the mysterious power to “detect” WiFi, cell signals, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. I was told I might find the Log Lady at church—perhaps the only church in America quiet enough for her to attend. I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural.

I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural. Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these.

Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these. The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics. Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead.

Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead. It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty.

It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty.