Jordana Cepelewicz in Quanta:

Practically every animal that scientists have studied — insects and cephalopods, amphibians and reptiles, birds and mammals — can distinguish between different numbers of objects in a set or sounds in a sequence. They don’t just have a sense of “greater than” or “less than,” but an approximate sense of quantity: that two is distinct from three, that 15 is distinct from 20. This mental representation of set size, called numerosity, seems to be “a general ability,” and an ancient one, said Giorgio Vallortigara, a neuroscientist at the University of Trento in Italy.

Practically every animal that scientists have studied — insects and cephalopods, amphibians and reptiles, birds and mammals — can distinguish between different numbers of objects in a set or sounds in a sequence. They don’t just have a sense of “greater than” or “less than,” but an approximate sense of quantity: that two is distinct from three, that 15 is distinct from 20. This mental representation of set size, called numerosity, seems to be “a general ability,” and an ancient one, said Giorgio Vallortigara, a neuroscientist at the University of Trento in Italy.

Now, researchers are uncovering increasingly more complex numerical abilities in their animal subjects. Many species have displayed a capacity for abstraction that extends to performing simple arithmetic, while a select few have even demonstrated a grasp of the quantitative concept of “zero” — an idea so paradoxical that very young children sometimes struggle with it.

More here.

Reviewing all of the region’s military interventions between 2010 and 2020, our research

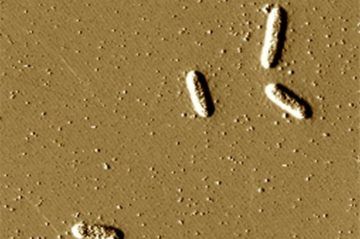

Reviewing all of the region’s military interventions between 2010 and 2020, our research  For decades, scientists suspected that bacteria known as Geobacter could clean up radioactive uranium waste, but it wasn’t clear how the microbes did it.

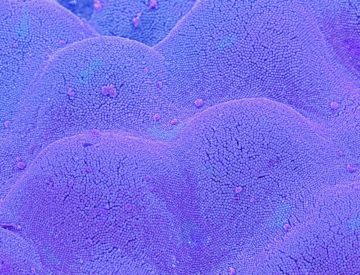

For decades, scientists suspected that bacteria known as Geobacter could clean up radioactive uranium waste, but it wasn’t clear how the microbes did it. Our main goal is to begin deciphering the molecular communication between bacteria (and the small molecules they secrete) and host cells in the small intestine. We’re particularly interested in enteroendocrine cells — cells found in the lining of the small intestine and throughout the intestinal tract — and how the small-intestine microbiome prompts them to release hormones. We also want to explore how this communication allows gut bacteria to alter physiology throughout the body. We know that gut bacteria affect biological processes in distal places such as the brain and skeletal muscles. I believe that bacterial communication with enteroendocrine cells is a major mechanism. These cells secrete hormones and neurotransmitters, and they also talk to neurons, sending signals across the body. We know there are physical interactions, where bacteria adhere to host cells. There are also chemical-signaling interactions, where intestinal cells sense and react to small molecules produced by microbes. We don’t yet understand the full context or implications of this molecular language in the small intestine. We hope to begin probing which small molecules the enteroendocrine cells respond to, which bacteria produce these molecules, which receptors they bind to, and how that translates to changes in biological processes. Our hope is to provide valuable novel therapeutic targets, not just for metabolic disorders, but also for neuropsychiatric conditions, and disorders influenced by the microbiome.

Our main goal is to begin deciphering the molecular communication between bacteria (and the small molecules they secrete) and host cells in the small intestine. We’re particularly interested in enteroendocrine cells — cells found in the lining of the small intestine and throughout the intestinal tract — and how the small-intestine microbiome prompts them to release hormones. We also want to explore how this communication allows gut bacteria to alter physiology throughout the body. We know that gut bacteria affect biological processes in distal places such as the brain and skeletal muscles. I believe that bacterial communication with enteroendocrine cells is a major mechanism. These cells secrete hormones and neurotransmitters, and they also talk to neurons, sending signals across the body. We know there are physical interactions, where bacteria adhere to host cells. There are also chemical-signaling interactions, where intestinal cells sense and react to small molecules produced by microbes. We don’t yet understand the full context or implications of this molecular language in the small intestine. We hope to begin probing which small molecules the enteroendocrine cells respond to, which bacteria produce these molecules, which receptors they bind to, and how that translates to changes in biological processes. Our hope is to provide valuable novel therapeutic targets, not just for metabolic disorders, but also for neuropsychiatric conditions, and disorders influenced by the microbiome. I’m not gonna say that Everybody Wants Some!!, the film by Richard Linklater, is a great movie. It is not. But it’s pretty good. We should also just appreciate a film that has not one but two!! exclamation marks in its official title. And yet, something nags at me about the title, that sentence, everybody wants some. What is it that everybody wants? Some. Some what? Well sex, of course, everbody wants some sex. And most of the people in the film are chasing after sex, especially the jocks on the baseball team, our ostensive heroes, the protagonists of the film if there are any protagonists in this film. They want to have as much sex as possible, those baseball jocks, and a few of them get just that. They also want something to do with baseball. They want to become baseball players of a professional sort. They want some fame, some glory, the glory of sport. Probably they want some money also, the money that goes along with the glory and that overlaps to at least some degree with the sex. Sex, glory, and money. That is what they want some of.

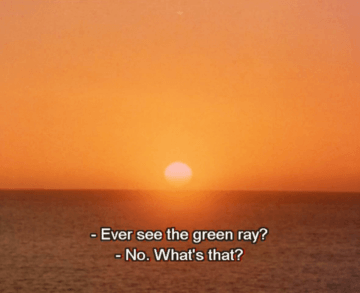

I’m not gonna say that Everybody Wants Some!!, the film by Richard Linklater, is a great movie. It is not. But it’s pretty good. We should also just appreciate a film that has not one but two!! exclamation marks in its official title. And yet, something nags at me about the title, that sentence, everybody wants some. What is it that everybody wants? Some. Some what? Well sex, of course, everbody wants some sex. And most of the people in the film are chasing after sex, especially the jocks on the baseball team, our ostensive heroes, the protagonists of the film if there are any protagonists in this film. They want to have as much sex as possible, those baseball jocks, and a few of them get just that. They also want something to do with baseball. They want to become baseball players of a professional sort. They want some fame, some glory, the glory of sport. Probably they want some money also, the money that goes along with the glory and that overlaps to at least some degree with the sex. Sex, glory, and money. That is what they want some of. The road from SARS-CoV-2’s “immunity shield” or “sheep’s clothing” to its Achilles’ heel involved several state-of-the-art research techniques. In collaboration with Peter Hinterdorfer of the Institute of Biophysics at the University of Linz, Austria, the team used high-tech biophysical methods to analyze how the

The road from SARS-CoV-2’s “immunity shield” or “sheep’s clothing” to its Achilles’ heel involved several state-of-the-art research techniques. In collaboration with Peter Hinterdorfer of the Institute of Biophysics at the University of Linz, Austria, the team used high-tech biophysical methods to analyze how the  In the 1980s, I got to know a man who seemed to be the walking embodiment of privilege. He was an elderly but vigorous WASP, tall and lean, with ancestry in this country that reached back to the seventeenth century. A Princeton man, he had gone into finance and risen to become CEO and chairman of a major regional bank. He had one of those WASP names one can barely resist satirizing, but he had been known all his life by his childhood nickname, Curly.

In the 1980s, I got to know a man who seemed to be the walking embodiment of privilege. He was an elderly but vigorous WASP, tall and lean, with ancestry in this country that reached back to the seventeenth century. A Princeton man, he had gone into finance and risen to become CEO and chairman of a major regional bank. He had one of those WASP names one can barely resist satirizing, but he had been known all his life by his childhood nickname, Curly. The

The  “No one who saw the photo thought I would survive,” said Mohammad Zubair, describing an image, taken by Siddiqui, which came to define last year’s anti-Muslim pogrom in New Delhi. Zubair was beaten by a mob of Hindu men, many wearing bike helmets. “It was like a war zone,” Siddiqui said, recounting how he had walked over the rubble of broken bricks and batons. He stood about a yard away from the group, his mask flecked with Zubair’s blood. He was spotted, and the attackers paused, looking right at his camera. Siddiqui fled just as Zubair lost consciousness. A group of young Muslim boys found Zubair and asked the neighborhood doctor to perform emergency stitches on his head wounds. Siddiqui looked for him later, relieved to find him alive in a local hospital. He made a portrait against the pale blue wall of the intensive treatment wing, Zubair’s head wrapped in gauze, eyes bruised and swollen. Siddiqui often said that he photographed “the human face of a breaking story.”

“No one who saw the photo thought I would survive,” said Mohammad Zubair, describing an image, taken by Siddiqui, which came to define last year’s anti-Muslim pogrom in New Delhi. Zubair was beaten by a mob of Hindu men, many wearing bike helmets. “It was like a war zone,” Siddiqui said, recounting how he had walked over the rubble of broken bricks and batons. He stood about a yard away from the group, his mask flecked with Zubair’s blood. He was spotted, and the attackers paused, looking right at his camera. Siddiqui fled just as Zubair lost consciousness. A group of young Muslim boys found Zubair and asked the neighborhood doctor to perform emergency stitches on his head wounds. Siddiqui looked for him later, relieved to find him alive in a local hospital. He made a portrait against the pale blue wall of the intensive treatment wing, Zubair’s head wrapped in gauze, eyes bruised and swollen. Siddiqui often said that he photographed “the human face of a breaking story.” It was embarrassingly obvious that

It was embarrassingly obvious that  D

D The first quarter of the twenty-first century has been an uneasy time of rupture and anxiety, filled with historic challenges and opportunities. In that close to twenty-five-year span, the United States witnessed the ominous opening shot of September 11, followed by the seemingly unending Afghanistan and Iraq wars, the effort to control HIV/AIDS, the 2008 recession, the election of the first African American president, the legalization of same-sex marriage, the contentious reign of Donald Trump, the stepped-up restriction of immigrants, the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and the coronavirus pandemic, just to name a few major events. Intriguingly, the essay has blossomed during this time, in what many would deem an exceptionally good period for literary nonfiction—if not a golden one, then at least a silver: I think we can agree that there has been a remarkable outpouring of new and older voices responding to this perplexing moment in a form uniquely amenable to the processing of uncertainty.

The first quarter of the twenty-first century has been an uneasy time of rupture and anxiety, filled with historic challenges and opportunities. In that close to twenty-five-year span, the United States witnessed the ominous opening shot of September 11, followed by the seemingly unending Afghanistan and Iraq wars, the effort to control HIV/AIDS, the 2008 recession, the election of the first African American president, the legalization of same-sex marriage, the contentious reign of Donald Trump, the stepped-up restriction of immigrants, the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and the coronavirus pandemic, just to name a few major events. Intriguingly, the essay has blossomed during this time, in what many would deem an exceptionally good period for literary nonfiction—if not a golden one, then at least a silver: I think we can agree that there has been a remarkable outpouring of new and older voices responding to this perplexing moment in a form uniquely amenable to the processing of uncertainty. CO2 concentrations now sit at 412 ppm, Earth’s temperature is a full 1.3 °C (2.3 °F) above pre-industrial levels, and still, no meaningful, sustained initiatives to reduce our global carbon emissions have been taken. In fact, they’re presently at an all-time high. The longer we delay meaningful climate action, the more severe the consequences will get not just for all of humanity today, but for generations and even millennia to come. Although our climate future intimately depends on how global emissions unfold in the coming years and decades, the latest IPCC report provides unprecedented clarity on a number of important issues. Here are the top six takeaways we should all accept and understand.

CO2 concentrations now sit at 412 ppm, Earth’s temperature is a full 1.3 °C (2.3 °F) above pre-industrial levels, and still, no meaningful, sustained initiatives to reduce our global carbon emissions have been taken. In fact, they’re presently at an all-time high. The longer we delay meaningful climate action, the more severe the consequences will get not just for all of humanity today, but for generations and even millennia to come. Although our climate future intimately depends on how global emissions unfold in the coming years and decades, the latest IPCC report provides unprecedented clarity on a number of important issues. Here are the top six takeaways we should all accept and understand. In June, an unprecedented heat wave in the Pacific Northwest killed hundreds of people and shattered records in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. Canada logged a new national record high when a town in British Columbia soared to 121.3 degrees Fahrenheit.

In June, an unprecedented heat wave in the Pacific Northwest killed hundreds of people and shattered records in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. Canada logged a new national record high when a town in British Columbia soared to 121.3 degrees Fahrenheit.