Peter Frankopan at The Guardian:

Antwerp is the star of this charming and rather lovely history. The “trade of the whole world”, wrote the Venetian ambassador and cardinal Bernardo Navagero in the middle of the 16th century, could be found in this city. It was hardly an exaggeration: all kinds of spices could be bought there; so too could books and art, produced by the score for all tastes and inclinations; when William Cecil wanted “little pillars of marble” for Burghley House – along with a ready-made classical gallery – it was to Antwerp that he turned.

Antwerp is the star of this charming and rather lovely history. The “trade of the whole world”, wrote the Venetian ambassador and cardinal Bernardo Navagero in the middle of the 16th century, could be found in this city. It was hardly an exaggeration: all kinds of spices could be bought there; so too could books and art, produced by the score for all tastes and inclinations; when William Cecil wanted “little pillars of marble” for Burghley House – along with a ready-made classical gallery – it was to Antwerp that he turned.

It was not just goods and products that could be acquired, for in Antwerp everything had a price, including knowledge, information and secrets – although distinguishing truth from scurrilous rumours was not easy, especially when it came to sex.

more here.

Illich was a purveyor of impossible truths, truths so radical that they questioned the very foundations of modern certitudes — progress, economic growth, health, education, mobility. While he was not wrong, we had all been riding on a train going in the opposite direction for so long that it was hard to see how, in any practical sense, the momentum could ever be stalled. And that was his point. Now that “the shadow our future throws” of which Illich warned is darkening the skies of the present, it is time to reconsider his thought.

Illich was a purveyor of impossible truths, truths so radical that they questioned the very foundations of modern certitudes — progress, economic growth, health, education, mobility. While he was not wrong, we had all been riding on a train going in the opposite direction for so long that it was hard to see how, in any practical sense, the momentum could ever be stalled. And that was his point. Now that “the shadow our future throws” of which Illich warned is darkening the skies of the present, it is time to reconsider his thought. For an entire year that involved emergency room visits, legal proceedings, involuntary unemployment and the death of loved ones, Mehran Nazir struggled with a depressive episode. He would find his mind flooded with self-destructive thoughts. He’d faintly hope his plane from Newark to San Francisco would crash or that he would doze off at the wheel of his car and end up in a fatal accident. The normally extroverted Nazir would lie paralyzed in bed for hours doing nothing, not wanting to speak with family and canceling plans with friends. It came to a head when Nazir found himself on the brink of suicide. In his darkest moment, he drafted a will and decided where it would happen.

For an entire year that involved emergency room visits, legal proceedings, involuntary unemployment and the death of loved ones, Mehran Nazir struggled with a depressive episode. He would find his mind flooded with self-destructive thoughts. He’d faintly hope his plane from Newark to San Francisco would crash or that he would doze off at the wheel of his car and end up in a fatal accident. The normally extroverted Nazir would lie paralyzed in bed for hours doing nothing, not wanting to speak with family and canceling plans with friends. It came to a head when Nazir found himself on the brink of suicide. In his darkest moment, he drafted a will and decided where it would happen. There are many variations to Hans Christian Andersen’s classic literary folktale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” but most have the same basic plot points: A vain emperor is duped by two con men into buying clothes that don’t exist. They trick him by saying that the non-existent fabric is actually visible, but only stupid and incompetent people can’t see it. The emperor pretends that he can see the clothes, and then ordinary people follow his lead — whether because they believe him, or because they are simply afraid to state otherwise. It is only when a child blurts out that he is naked that the illusion is shattered.

There are many variations to Hans Christian Andersen’s classic literary folktale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” but most have the same basic plot points: A vain emperor is duped by two con men into buying clothes that don’t exist. They trick him by saying that the non-existent fabric is actually visible, but only stupid and incompetent people can’t see it. The emperor pretends that he can see the clothes, and then ordinary people follow his lead — whether because they believe him, or because they are simply afraid to state otherwise. It is only when a child blurts out that he is naked that the illusion is shattered. Octavian Report: Why should we read the Odyssey?

Octavian Report: Why should we read the Odyssey? As Soare (2013) recounts,

As Soare (2013) recounts,  In the wreckage of World War I, it was hard to imagine a return to this borderless “economic Eldorado.” But today, it’s the relatively self-contained national economies of the mid-twentieth century that may seem like a lost world. To access the products of the whole earth, you don’t even have to pick up the phone; you can just log onto Amazon.

In the wreckage of World War I, it was hard to imagine a return to this borderless “economic Eldorado.” But today, it’s the relatively self-contained national economies of the mid-twentieth century that may seem like a lost world. To access the products of the whole earth, you don’t even have to pick up the phone; you can just log onto Amazon. Naturally, there is something contradictory to be found in the emphasis on the “I” in Didion’s work and the supposed “sublime neutrality” which she represents. Considering the omnipresence of the former, the latter seems more or less unattainable. For many Didion readers, who simply cannot shake free of the need to label no matter how hard they wriggle, this paradox might seem unimportant. For me, it is the crux of her work, highlighted in her new collection of essays, Let Me Tell You What I Mean. Encapsulating many pieces from Didion’s emergence with her ‘Points West’ column which she shared with her husband, John Gregory Dunne, as well as later work for establishments like the New York Times Magazine and New Yorker, the collection is a continuation of Didion’s lifelong search for that meagre, almost incommunicable slice of the world where subjectivity and transparency live together hand in hand.

Naturally, there is something contradictory to be found in the emphasis on the “I” in Didion’s work and the supposed “sublime neutrality” which she represents. Considering the omnipresence of the former, the latter seems more or less unattainable. For many Didion readers, who simply cannot shake free of the need to label no matter how hard they wriggle, this paradox might seem unimportant. For me, it is the crux of her work, highlighted in her new collection of essays, Let Me Tell You What I Mean. Encapsulating many pieces from Didion’s emergence with her ‘Points West’ column which she shared with her husband, John Gregory Dunne, as well as later work for establishments like the New York Times Magazine and New Yorker, the collection is a continuation of Didion’s lifelong search for that meagre, almost incommunicable slice of the world where subjectivity and transparency live together hand in hand.

As his armies conquered most of Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte demonstrated an insatiable desire to steal art. These were not smash-and-grab operations. According to Cynthia Saltzman’s marvelous book, “Plunder: Napoleon’s Theft of Veronese’s Feast,” he sought out experts to advise him on which cultural treasures to ship back to Paris. Napoleon wanted to expand the art collection in the Louvre palace. He wrote to France’s five-member governing committee to “send three or four known artists” to choose the best paintings and sculptures.

As his armies conquered most of Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte demonstrated an insatiable desire to steal art. These were not smash-and-grab operations. According to Cynthia Saltzman’s marvelous book, “Plunder: Napoleon’s Theft of Veronese’s Feast,” he sought out experts to advise him on which cultural treasures to ship back to Paris. Napoleon wanted to expand the art collection in the Louvre palace. He wrote to France’s five-member governing committee to “send three or four known artists” to choose the best paintings and sculptures. S

S Neruda’s declaration that “the reality of the world … should not be underprized” implies that we can and often do underprize it. We grow away from our primary relish of the phenomena. The rooms where we come to consciousness, the cupboards we open as toddlers, the shelves we climb up to, the boxes and albums we explore in reserved places in the house, the spots we discover for ourselves in those first solitudes out of doors, the haunts of those explorations at the verge of our security—in such places and at such moments “the reality of the world” first wakens in us. It is also at such moments that we have our first inkling of pastness and find our physical surroundings invested with a wider and deeper dimension than we can, just then, account for.

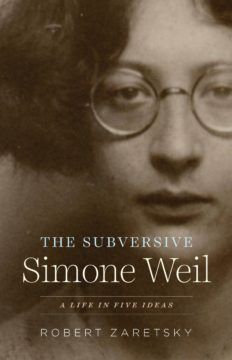

Neruda’s declaration that “the reality of the world … should not be underprized” implies that we can and often do underprize it. We grow away from our primary relish of the phenomena. The rooms where we come to consciousness, the cupboards we open as toddlers, the shelves we climb up to, the boxes and albums we explore in reserved places in the house, the spots we discover for ourselves in those first solitudes out of doors, the haunts of those explorations at the verge of our security—in such places and at such moments “the reality of the world” first wakens in us. It is also at such moments that we have our first inkling of pastness and find our physical surroundings invested with a wider and deeper dimension than we can, just then, account for. Simone Weil was difficult for those who knew her in life and no less difficult for those who encounter her now, through the writings that survived her death at the age of 34 in 1943. Robert Zaretsky’s new intellectual biography, The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas (2021), evokes several difficulties in its epilogue. Weil’s character was “extreme.” Her ideas were largely impractical (“at worst inhuman”). He calls her attitude “merciless.” And yet, “I cannot resist returning time and again to this remarkable individual,” Zaretsky writes. She led an “exemplary” life. “For many of her readers,” he suggests, “Weil’s life has all the trappings of secular sainthood.”

Simone Weil was difficult for those who knew her in life and no less difficult for those who encounter her now, through the writings that survived her death at the age of 34 in 1943. Robert Zaretsky’s new intellectual biography, The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas (2021), evokes several difficulties in its epilogue. Weil’s character was “extreme.” Her ideas were largely impractical (“at worst inhuman”). He calls her attitude “merciless.” And yet, “I cannot resist returning time and again to this remarkable individual,” Zaretsky writes. She led an “exemplary” life. “For many of her readers,” he suggests, “Weil’s life has all the trappings of secular sainthood.” Neo-Malthusians credited environmental feedback loops, not moral failings, for regime collapse. In the 1960s and ’70s, works by Paul Ehrlich and Donella Meadows et al argued that the world’s population was growing so fast it would soon outstrip resource supplies, leading to (among other things) widespread food shortages. More recently, Jared Diamond wrote of the role that environmental depletion and diseases played in the fall of civilisations, and his theory that the collapse of Easter Island resulted from overexploitation of the natural environment has enjoyed particular resonance. For its part, the

Neo-Malthusians credited environmental feedback loops, not moral failings, for regime collapse. In the 1960s and ’70s, works by Paul Ehrlich and Donella Meadows et al argued that the world’s population was growing so fast it would soon outstrip resource supplies, leading to (among other things) widespread food shortages. More recently, Jared Diamond wrote of the role that environmental depletion and diseases played in the fall of civilisations, and his theory that the collapse of Easter Island resulted from overexploitation of the natural environment has enjoyed particular resonance. For its part, the