Kelefa Sanneh at The New Yorker:

Wilkes, who is thirty-one, grew up in Connecticut, and Gendel, who is thirty-five, grew up in central California. Both were drawn to Los Angeles by way of the jazz program at the University of Southern California. They turned out to have mixed feelings about studying jazz in a university setting. And maybe they had mixed feelings, too, about being tied to a tradition that arouses as much strong feeling—and, worse, as much weak feeling—as jazz does. As a boy, Wilkes was obsessed with the Grateful Dead and Phish, which gave him a love of improvisation. By the time he applied to U.S.C., he was a proficient electric-bass player, and, although he knew that the jazz program typically accepted only upright-bass players, he figured that the jazz bureaucracy might make an exception for him. It did not, and so he studied R. & B. and funk instead, working with a string of legendary musicians, including Patrice Rushen, an esteemed composer and keyboardist, and Leon (Ndugu) Chancler, a drum virtuoso. This was not a sad story: it turned out that Wilkes loved session playing, which demands precision and adaptability, and he had no complaints about his college experience. But, as Wilkes talked in the studio, Gendel grew outraged on his behalf—he couldn’t abide the idea that a jazz department would reject an eager student just because he played the wrong instrument. “It’s the most anti-jazz, anti-open-minded mentality I can imagine,” he said, becoming more animated than he’d been all afternoon. “This is why I’m against it all. It’s just stupid!”

Wilkes, who is thirty-one, grew up in Connecticut, and Gendel, who is thirty-five, grew up in central California. Both were drawn to Los Angeles by way of the jazz program at the University of Southern California. They turned out to have mixed feelings about studying jazz in a university setting. And maybe they had mixed feelings, too, about being tied to a tradition that arouses as much strong feeling—and, worse, as much weak feeling—as jazz does. As a boy, Wilkes was obsessed with the Grateful Dead and Phish, which gave him a love of improvisation. By the time he applied to U.S.C., he was a proficient electric-bass player, and, although he knew that the jazz program typically accepted only upright-bass players, he figured that the jazz bureaucracy might make an exception for him. It did not, and so he studied R. & B. and funk instead, working with a string of legendary musicians, including Patrice Rushen, an esteemed composer and keyboardist, and Leon (Ndugu) Chancler, a drum virtuoso. This was not a sad story: it turned out that Wilkes loved session playing, which demands precision and adaptability, and he had no complaints about his college experience. But, as Wilkes talked in the studio, Gendel grew outraged on his behalf—he couldn’t abide the idea that a jazz department would reject an eager student just because he played the wrong instrument. “It’s the most anti-jazz, anti-open-minded mentality I can imagine,” he said, becoming more animated than he’d been all afternoon. “This is why I’m against it all. It’s just stupid!”

more here.

I

I When Yas Crawford started feeling the effects of her chronic illness, she says she felt as if her body and mind were at war. “When you’re ill for a long time, your body takes over,” she says. “Your brain wants to do one thing, and your body does something else.”

When Yas Crawford started feeling the effects of her chronic illness, she says she felt as if her body and mind were at war. “When you’re ill for a long time, your body takes over,” she says. “Your brain wants to do one thing, and your body does something else.” My beloved if

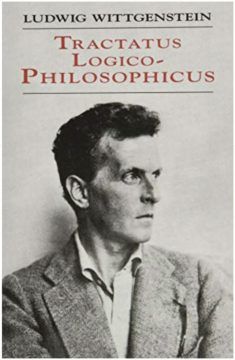

My beloved if Somewhere along the crooked scar of the eastern front, during those acrid summer months of the Brusilov Offensive in 1916, when the Russian Empire pierced into the lines of the Central Powers and perhaps more than one million men would be killed from June to September, a howitzer commander stationed with the Austrian 7th Army would pen gnomic observations in a notebook, having written a year before that the “facts of the world are not the end of the matter.” Among the richest men in Europe, the 27-year-old had the option to defer military service, and yet an ascetic impulse compelled Ludwig Wittgenstein into the army, even though he lacked any patriotism for the Austro-Hungarian cause. Only five years before his trench ruminations would coalesce into 1921’s

Somewhere along the crooked scar of the eastern front, during those acrid summer months of the Brusilov Offensive in 1916, when the Russian Empire pierced into the lines of the Central Powers and perhaps more than one million men would be killed from June to September, a howitzer commander stationed with the Austrian 7th Army would pen gnomic observations in a notebook, having written a year before that the “facts of the world are not the end of the matter.” Among the richest men in Europe, the 27-year-old had the option to defer military service, and yet an ascetic impulse compelled Ludwig Wittgenstein into the army, even though he lacked any patriotism for the Austro-Hungarian cause. Only five years before his trench ruminations would coalesce into 1921’s  Biotechnology company Moderna is preparing to begin human trials on HIV vaccines as early as Wednesday, using the same mRNA platform as the firm’s COVID-19 vaccine.

Biotechnology company Moderna is preparing to begin human trials on HIV vaccines as early as Wednesday, using the same mRNA platform as the firm’s COVID-19 vaccine. AT THE CASABLANCA Book Fair in Morocco back in 2009, the Iraqi poet Saadi Youssef was signing the seventh volume of his Complete Poetic Works. A flock of junior high school girls in their blue uniforms were standing nearby. One of them pointed to her friend, telling Youssef: “She, too, is a poet.” He smiled and gestured to the young poet to come forward. She hesitated: “I’m just a beginner.” “I, too, am a beginner. We are all beginners,” said Youssef. The septuagenarian who uttered those words is widely recognized as one of the greatest modern Arab poets. When he uttered those words, he had been writing and publishing poetry for more than half a century. It was neither a hyperbolic statement, nor false modesty on his part. Well into his 80s, one of the most remarkable features of Youssef’s poetry (and his persona) was his restlessness. He was audacious (even reckless, at times) and on an incessant quest for new beginnings.

AT THE CASABLANCA Book Fair in Morocco back in 2009, the Iraqi poet Saadi Youssef was signing the seventh volume of his Complete Poetic Works. A flock of junior high school girls in their blue uniforms were standing nearby. One of them pointed to her friend, telling Youssef: “She, too, is a poet.” He smiled and gestured to the young poet to come forward. She hesitated: “I’m just a beginner.” “I, too, am a beginner. We are all beginners,” said Youssef. The septuagenarian who uttered those words is widely recognized as one of the greatest modern Arab poets. When he uttered those words, he had been writing and publishing poetry for more than half a century. It was neither a hyperbolic statement, nor false modesty on his part. Well into his 80s, one of the most remarkable features of Youssef’s poetry (and his persona) was his restlessness. He was audacious (even reckless, at times) and on an incessant quest for new beginnings. Hi. My name is Marc. I’m a guitarist who points extremely loud amplifiers directly at his head. Very often. Sometimes as often as 200 nights a year for the past 45 years. Audiologists say this could make one’s ears howl, create an uncomfortable sensation of density in one’s head, and eventually make it impossible to hear human conversation. Yet I persist . . . Why?

Hi. My name is Marc. I’m a guitarist who points extremely loud amplifiers directly at his head. Very often. Sometimes as often as 200 nights a year for the past 45 years. Audiologists say this could make one’s ears howl, create an uncomfortable sensation of density in one’s head, and eventually make it impossible to hear human conversation. Yet I persist . . . Why? L

L In the past few weeks, the Biden administration’s domestic agenda has come into sharp focus: a bipartisan Senate bill for physical and environmental infrastructure projects nearing passage; new statistics showing that COVID-19 relief has dramatically reduced poverty across demographic groups; an executive order aimed at concentrated market power, promoting competition and worker power; a $3.5 trillion budget proposal with large outlays in social spending, paid for by taxes on the rich and corporations; presidential speeches on behalf of better jobs for Americans at the bottom and middle of the economy. The sum of these and other policies is more ambitious, and more ideologically pointed, than the Biden campaign slogan “Build Back Better.” President Biden is using the resources of the federal government to reverse nearly half a century of growing monopoly, plutocracy, and inequality. Regardless of whether this agenda goes far enough, or whether Congress allows it to go anywhere at all, the administration is pointing the country in a fundamentally new direction.

In the past few weeks, the Biden administration’s domestic agenda has come into sharp focus: a bipartisan Senate bill for physical and environmental infrastructure projects nearing passage; new statistics showing that COVID-19 relief has dramatically reduced poverty across demographic groups; an executive order aimed at concentrated market power, promoting competition and worker power; a $3.5 trillion budget proposal with large outlays in social spending, paid for by taxes on the rich and corporations; presidential speeches on behalf of better jobs for Americans at the bottom and middle of the economy. The sum of these and other policies is more ambitious, and more ideologically pointed, than the Biden campaign slogan “Build Back Better.” President Biden is using the resources of the federal government to reverse nearly half a century of growing monopoly, plutocracy, and inequality. Regardless of whether this agenda goes far enough, or whether Congress allows it to go anywhere at all, the administration is pointing the country in a fundamentally new direction. Arjun Jayadev and J.W. Mason in Boston Review:

Arjun Jayadev and J.W. Mason in Boston Review: Virginia Jackson on the late Lauren Berlant, over at Critical Inquiry:

Virginia Jackson on the late Lauren Berlant, over at Critical Inquiry: Kate Aronoff in The New Republic:

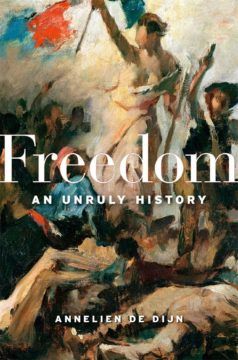

Kate Aronoff in The New Republic: Aziz Huq in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Aziz Huq in the Los Angeles Review of Books: