Category: Archives

Saturday, March 30, 2024

Metaperson: The enchanted worlds of Marshall Sahlins

Anna Della Subin in The Nation:

As a god, or any divine power, only a mirage of the human-made political structures that oppress us? This understanding of religion, popularized by 19th-century thinkers like Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, has become received wisdom among the anthropologists and sociologists studying the origins and functions of religious life. We sense that we live under forces of authority that constrain us, and yet we cannot precisely locate or understand them. Needing to give some shape or form to this coercion, we project it onto the clouds, fashioning heavenly beings that are ultimately deifications of the human state. “Religion is realistic,” Durkheim noted; it corresponds to our social realities and reinforces them.

Yet the existence of societies without chiefs or kings, or any vertical political organization, challenges this picture. In communities that traditionally recognized no rulers or government, from Tierra del Fuego to the Central Arctic to the Philippines, we still find complex concepts of celestial hierarchies, metahuman authorities, and bureaucracies of deities and spirits with no correspondence to the human social order. Where do these ideas come from, which reflect no living conditions on the ground? How is it that notions of the state seem to be anticipated by cosmology before they are realized in society?

More here.

Raymond Williams’s Resources for Hope

Jedediah Britton-Purdy in Dissent:

All sorts of people had come to the Welsh countryside to spend the day talking about the history of labor radicalism: miners, organizers, researchers, politicians. But the star attraction was missing. Raymond Williams, the Cambridge scholar and socialist beacon, had agreed by letter to speak; rumor was that he would be arriving in a big car. Then, as a runner returned from the parking area to report the distressing news that no big car had arrived, a tall, craggy-featured man rose from the audience and made his way to the stage. He had been there all day, listening, watching, content among his people, not making a point of himself. There was no need to make a point; everyone in that world knew his name. It was not a merely local fame. Zadie Smith recalls that when she was an undergraduate at Cambridge in the 1990s, Williams sat beside Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes in the pantheon of social and literary theorists. He was Stuart Hall’s friend and collaborator, E.P. Thompson’s ally and sparring partner, Terry Eagleton’s teacher, and often worked side by side with Perry Anderson. When he died in 1988, Robin Blackburn wrote in the New Left Review that Williams was the “most authoritative, consistent, and radical voice” of the British left.

Asked to give an account of himself, Williams would begin, “I come from Pandy.” The Welsh village of Pandy sits a short walk across fields from the English border, at the edge of the Black Mountains. The peaks near Pandy rise more than 1,000 feet above the farmland of the valleys. A person can always walk to higher ground for a long and encompassing view. When Williams was young there, in the 1920s and ’30s, the view from the ridges included smoke coming from ironworks and coal pits less than twenty miles to the south and west. At night, the flames of the industrial valleys edged the black horizon with red.

More here.

The Gaza Strip Has Been Destroyed. So Has Hope For A Fair Future For The Two Peoples.

Amira Hass in Hammer and Hope:

I write these words from the West Bank with a profound sense of grief and defeat, as the clashing terms of victory, genocide, erasure, heroic struggle, and historic achievement come up again and again in reference to the Palestinian people and to Gazans in particular.

The Gaza Strip cast a spell on me, as it did for many who visited it and came to know its people. It was an inseparable part of historic Palestine until it was cut off after the creation of the state of Israel and the expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948-49. As a result, it emerged as a distinct sociological and geopolitical entity. Its core characteristic was its high proportion of refugees (about 75 percent of its population), whose roots were in dozens of villages and towns that Israel depopulated and destroyed.

The Gaza Strip we knew as a compact geographical entity of 365 square kilometers was still large enough to contain the diversity of village and city, of new neighborhoods and old, of the shore and the hills, of poor and rich, of refugees and native-born. And it was small and crowded, so its people lived in one another’s pockets, more and more as their numbers grew, and it felt that everyone knew everyone else and there were no secrets. It was so small and tightly bound it seemed that all people living there took an active part in whatever political, social, and military events were going on.

More here.

Daniel Kahneman & Yuval Noah Harari in conversation

How Not to Think Like a Fascist

Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as “sculpting with lava.”

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as “sculpting with lava.”

Even Phillips’s titles tell us only so much. “Attention Seeking” (2019) sounds as if it’s about something shameful, when in fact, he says, “attention-seeking is one of the best things we do.” In “On Wanting to Change” (2021), he writes about change as an object of both desire and dread; we long for the conclusiveness of a conversion experience, “a change that will finally put a stop to the need for change.”

Phillips, who was formerly a child psychotherapist, likes to play with terms that are capacious, elastic and stubbornly ambiguous. The title of his new book, “On Giving Up,” covers the vast territory between hope and despair. We can give up smoking, sugar or a bad habit; but we can also give up on ourselves. “We give things up when we believe we can change; we give up when we believe we can’t.”

More here.

The Deep Roots Of AI

Sukhdev Sandhu at The Guardian:

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as Friedrich Kittler, Donna Haraway and N Katherine Hayles. For the most part, it’s a call for rhetorical de-escalation. Relax, he says, machines and literature go back a long way; his goal is to reconstruct “the modern chatbot from parts found on the workbench of history” using “strings of anecdote and light philosophical commentary”.

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as Friedrich Kittler, Donna Haraway and N Katherine Hayles. For the most part, it’s a call for rhetorical de-escalation. Relax, he says, machines and literature go back a long way; his goal is to reconstruct “the modern chatbot from parts found on the workbench of history” using “strings of anecdote and light philosophical commentary”.

This chatbot backstory begins with Arab philosopher Ibn Khaldun’s 1377 Muqaddimah, which includes a description of “zairajah”, a kind of “letter magic” performed via a sort of horoscope, in which a large circle encloses other circles which, in turn, represent various elements and branches of science. Was this an apparatus for analogical reasoning? For astrological projections?

more here.

The Notebooks Of Sonny Rollins

Dwight Garner at the New York Times:

It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.”

It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.”

He began to practice alone, often at night, on the Williamsburg Bridge. A novelist might view this scene from avian heights, swooping down the East River, in and out of his grainy, Dopplered wail. As Rollins aged, accolades began to settle on his head and shoulders the way pigeons do on statues in the Piazza San Marco in Venice. Fame and honor were not enough to assuage his fears when he and his wife bought a house in upstate New York; a Black man and a white woman couldn’t live anywhere too isolated because interracial marriage still drew outrage.

more here.

Sonny Rollins – St. Thomas

Saturday Poem

Villanelle

The crack is moving down the wall,

Defective plaster isn’t all the cause.

We Must remain until the roof falls in.

It’s mildly cheering to recall

That every building has its little flaws.

The crack is moving down the wall.

Here in the kitchen drinking gin,

We can accept the damndest laws.

We Must remain until the roof falls in.

And though there’s no one here at all,

One searches every room because

The crack is moving down the wall.

Repairs? But how can one begin?

The lease has warnings buried in each clause.

We Must remain until the roof falls in.

These nights one hears a creaking in the hall,

The sort of thing that gives one pause.

The crack is moving down the wall.

We Must remain until the roof falls in.

by Weldon Kees

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins,1986

Friday, March 29, 2024

Why a New Adaptation of “The Master and Margarita” is Setting Russian Society Aflame

Cameron Manley at Literary Hub:

One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own.

One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own.

Bulgakov’s work was highly controversial at the time for its allegorical anti-Soviet rhetoric. Much like his protagonist, the author, out of despair for the suffocating climate of Stalinist repression, consigned the initial draft of his manuscript to the flames. The subsequent treatment of the novel by authorities—censored to the point of butchery—has long been viewed as a prime example of the Bulgakov’s central point.

Michael Lockshin’s new screen adaptation of Bulgakov’s opus appears to be heading down a similar path.

More here.

How Our Cells Strategize To Keep Us Alive

Dan Levitt in Time:

Our cells, each composed of 100 trillion atoms made of particles from the Big Bang, are filled with all kinds of structures. These include organelles—little factories like energy-producing mitochondria—and tiny molecular machines like ATP synthase, whose rotor and shaft spin at up to 300 rpm to produce ATP, the molecules that transmit energy in our cells. The interior of our cells are also filled with all kinds of molecules randomly colliding at tremendous speeds. Water molecules, for example, zigzag at the astonishing speed of over 1 thousand miles an hour (although they only go about 4 billionths of an inch before they smack into another molecule). In addition to collisions, cells face a myriad of other threats from within and without. You might expect them to suffer the same fate as our cars and dishwashers and constantly break down. But they don’t. Your body has an ingenious three-part strategy to keep you out of the junkyard.

Our cells, each composed of 100 trillion atoms made of particles from the Big Bang, are filled with all kinds of structures. These include organelles—little factories like energy-producing mitochondria—and tiny molecular machines like ATP synthase, whose rotor and shaft spin at up to 300 rpm to produce ATP, the molecules that transmit energy in our cells. The interior of our cells are also filled with all kinds of molecules randomly colliding at tremendous speeds. Water molecules, for example, zigzag at the astonishing speed of over 1 thousand miles an hour (although they only go about 4 billionths of an inch before they smack into another molecule). In addition to collisions, cells face a myriad of other threats from within and without. You might expect them to suffer the same fate as our cars and dishwashers and constantly break down. But they don’t. Your body has an ingenious three-part strategy to keep you out of the junkyard.

The biophysicist Dan Kirschner told me that just thinking about everything that could go wrong in cells used to keep him awake at night. He was learning about cell development in a graduate school course just as his wife was about to have a baby. He was so overwhelmed by the many opportunities for mistakes that he feared his daughter would be born with a neck like a giraffe.

More here.

On Kahneman

“A Reality Club Discussion on the Work of Daniel Kahneman” from 2014 in Edge.org:

On the occasion of Daniel Kahneman’s 80th birthday on March 5, 2014, Edge celebrated with a reprise of a number of his contributions to our pages. (See Edge Master Class 2007, “A Short Course in Thinking About Thinking“; Edge Master Class 2008, “A Short Course in Behavioral Economics“; Kahneman’s talk on “The Marvels and Flaws of Intuitive Thinking” at the Edge Master Class 2011, “The Science of Human Nature.”

In the first Edge Master Class, “Thinking About Thinking” (2007), Kahneman was the teacher and the students were the founders and architects of Microsoft, Amazon, Google, PayPal, and Facebook, i.e. the individuals responsible for rewriting our global culture. Why did Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Larry Page (Google), Sergey Brin (Google), Nathan Myhrvold (Microsoft), Sean Parker (Facebook), Elon Musk (Space X, Tesla), Evan Williams (Twitter), Jimmy Wales (Wikipedia), among others, travel to Napa that year, and again in 2008, to listen to Kahneman? Because all kinds of things are new. Entirely new economic structures and pathways have come into existence in the past few years: New ideas in psychology, cognitive science, behavioral economics, law, and medicine that take a new look at risk, decision-making, and other aspects of human judgment.

“Danny Kahneman is simply the most distinguished living psychologist in the world, bar none,” writes Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert. “Trying to say something smart about Danny’s contributions to science is like trying to say something smart about water: It is everywhere, in everything, and a world without it would be a world unimaginably different than this one.”

More here.

Namit Arora: “Indian Civilization is an Idea But Also an Enigma”

The Path Is No Path: On Not Becoming a Poet

Bryan Vandyke in The Millions:

In my second year of college I applied for a spot in a creative writing program. If I got in, I could graduate in two years with a writing major. If I didn’t, well, I needed a new major. I fussed over the application for months. Attended info sessions, met with the program director, revised my portfolio of poems so often that one professor finally said, Bryan, relax. Let the poems speak. I didn’t grow up saying I wanted to be a writer, but the signs were there, like a secret wish I kept from everyone, myself included. A stroll through the half-hearted journals and failed diaries of my teenage years turns up observations like: “I want to write books, but you can’t make a living that way.” Such a Midwesterner: The arts just aren’t practical.

In my second year of college I applied for a spot in a creative writing program. If I got in, I could graduate in two years with a writing major. If I didn’t, well, I needed a new major. I fussed over the application for months. Attended info sessions, met with the program director, revised my portfolio of poems so often that one professor finally said, Bryan, relax. Let the poems speak. I didn’t grow up saying I wanted to be a writer, but the signs were there, like a secret wish I kept from everyone, myself included. A stroll through the half-hearted journals and failed diaries of my teenage years turns up observations like: “I want to write books, but you can’t make a living that way.” Such a Midwesterner: The arts just aren’t practical.

Then one cold October afternoon my parents came to visit campus and I stumbled through a confession of sorts: I want to be a poet, I said. I want to declare a major in poetry. To their credit, they took the news quite well. My mom, who captained the family finances, asked a familiar question: How does a poet make a living, exactly?

I got the good news on a Tuesday afternoon. I don’t know how many other people applied, but I felt like one of God’s own elect. I met with Mary Kinzie, the poet who ran the writing division. Her office had books piled on the desk and floor. Propped behind a chair in the corner was the promotional poster for a reading she gave at Barnes & Noble for Ghost Ship, her most recent book published by Knopf. Knopf! I can’t recall a word she said that day, just the halo of high hopes that encircled our conversation.

More here.

Human Nature – Israelis and Palestinians

(Note: Please take 12 minutes to listen to what this wise man said nine years ago.)

Friday Poem

My Son My Executioner

My son, my executioner,

…… I take you in my arms,

Quiet and small and just astir,

…… And whom my body warms.

Sweet death, small son, our instrument

…… Of immortality,

Your cries and hunger document

…… Our bodily decay.

We twenty-five and twenty-two,

…… Who seemed to live forever,

Observe enduring life in you

…… And start to die together.

by Donald Hall

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

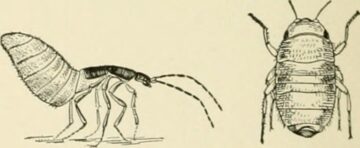

Are Insects Conscious?

Carrie Arnold at Noema:

However, a growing collection of new experiments is challenging the old consensus. Far from being six-legged automatons, they can experience feelings akin to pain and suffering, joy and desire. When Chittka gave bumblebees an extra jolt of sucrose, their favorite food, the bees buzzed with delight. Agitated, anxious honeybees, on the other hand, responded with pessimism when researchers shook them to simulate a predatory attack. Other researchers found that they “scream” when under threat. Ants display rudimentary counting abilities, can understand the concept of zero and make tools. Fruit flies learn from their peers. Cockroaches have complex social lives. Fruit flies drown themselves in booze when deprived of mating opportunities. Some earwigs and other insects play dead when threatened by a predator.

However, a growing collection of new experiments is challenging the old consensus. Far from being six-legged automatons, they can experience feelings akin to pain and suffering, joy and desire. When Chittka gave bumblebees an extra jolt of sucrose, their favorite food, the bees buzzed with delight. Agitated, anxious honeybees, on the other hand, responded with pessimism when researchers shook them to simulate a predatory attack. Other researchers found that they “scream” when under threat. Ants display rudimentary counting abilities, can understand the concept of zero and make tools. Fruit flies learn from their peers. Cockroaches have complex social lives. Fruit flies drown themselves in booze when deprived of mating opportunities. Some earwigs and other insects play dead when threatened by a predator.

In other words, insects have thoughts and feelings. The next question for philosophers and scientists alike is: Do they have consciousness?

more here.

Consciousness In Humans And Other Things

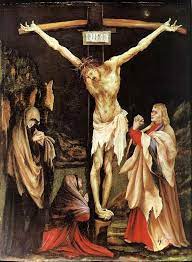

Matthias Grünewald’s Gruesome Good Friday

Ed Simon at Hyperallergic:

Though firmly a Renaissance painter in regard to technical acumen, Grünewald was Medieval in his vision, an inheritor of the 14th and 15th centuries’ comfort with the horrors of embodiment. In Germany, in particular, there existed then a form of devotion that took succor precisely in visualizing the sort of gruesome tableaux that Grünewald expertly painted, especially as regards the paradox of an almighty God himself suffering and dying. “Be assured of this,” wrote Suso’s contemporary, the mystic Thomas à Kempis in The Imitation of Christ (c. 1418–27), “that you must live a dying life.” The so-called Imitatio, whereby the penitent would imagine the degradations of the passion, was common in Medieval Catholicism, and reinvigorated by the Ignatian exercises of the Jesuits centuries later.

Though firmly a Renaissance painter in regard to technical acumen, Grünewald was Medieval in his vision, an inheritor of the 14th and 15th centuries’ comfort with the horrors of embodiment. In Germany, in particular, there existed then a form of devotion that took succor precisely in visualizing the sort of gruesome tableaux that Grünewald expertly painted, especially as regards the paradox of an almighty God himself suffering and dying. “Be assured of this,” wrote Suso’s contemporary, the mystic Thomas à Kempis in The Imitation of Christ (c. 1418–27), “that you must live a dying life.” The so-called Imitatio, whereby the penitent would imagine the degradations of the passion, was common in Medieval Catholicism, and reinvigorated by the Ignatian exercises of the Jesuits centuries later.

As such, nothing is philosophically novel in the Isenheim altarpiece, with its Christ who appears slick with the clammy sweat of death, stinking with the purification of the sepulcher. But to see something so ugly so perfectly depicted remains shocking five centuries later.

more here.