Will Glovinsky at Public Books:

It was 1968, and the “battle to feed all of humanity” had already been lost. In the coming 1970s, soaring populations and finite global resources would lead hundreds of millions of people to starve to death. Or so prophesized Paul and Anne Ehrlich in their book The Population Bomb. Paul Ehrlich, a Stanford entomologist, gained unlikely fame as an outrider of the apocalypse. He went on Johnny Carson and declared that “the end” was near.

But, notoriously, the Ehrlichs were wrong. They had predicted that vast swathes of humanity would die, yet by 1990, the human population had added some 1.5 billion people. Moreover, famines became much rarer, malnutrition decreased, and living standards rose across the industrializing world. To top it off, the Ehrlichs’ prognostications of scarcity came with generous servings of first-world environmentalist racism (he suggested food aid to India was pointless). They even inspired, from Mexico to Bangladesh, horrific campaigns of coerced sterilizations. As such, Ehrlich has become a byword for one of environmentalism’s most shortsighted—and morally bankrupt—impulses.

Yet one might also say, in hindsight, that the Ehrlichs were only wrong about which species would starve. In the second half of the 20th century, global human famine was averted by the Green Revolution’s formula of high-yield, semi-dwarf cereal varieties, synthetic fertilizers, chemical pesticides, monocrop agriculture, and intensified irrigation. These advances helped save perhaps two billion lives, yet the planet is strewn with the costs of this miracle. What The Population Bomb failed to predict was that we would largely survive by starving and poisoning countless species and ecosystems to the point of collapse.

More here.

“You need to work on your face.”

“You need to work on your face.” F

F Everett has spoken in the past with frustration about Erasure looming so large in his body of work. Does he still feel that way? “The only thing that ever pissed me off is that everyone agreed with it. No one took issue, or said: ‘It’s not like that.’” Why was that annoying? “I like the blowback. It’s interesting. There’s nothing worse than preaching to the choir, right?” Erasure came out in 2001, but people have taken American

Everett has spoken in the past with frustration about Erasure looming so large in his body of work. Does he still feel that way? “The only thing that ever pissed me off is that everyone agreed with it. No one took issue, or said: ‘It’s not like that.’” Why was that annoying? “I like the blowback. It’s interesting. There’s nothing worse than preaching to the choir, right?” Erasure came out in 2001, but people have taken American  Despite its notoriously opaque prose, Butler’s best-known book, “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” (1990), has been both credited and blamed for popularizing a multitude of ideas, including some that Butler doesn’t propound, like the notions that biology is entirely unreal and that everybody experiences gender as a choice.

Despite its notoriously opaque prose, Butler’s best-known book, “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” (1990), has been both credited and blamed for popularizing a multitude of ideas, including some that Butler doesn’t propound, like the notions that biology is entirely unreal and that everybody experiences gender as a choice. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, pen name Lewis Carroll, is best known as the Victorian-era author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Now, out of obscurity, comes

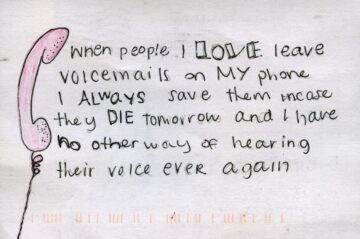

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, pen name Lewis Carroll, is best known as the Victorian-era author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Now, out of obscurity, comes  In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous.

In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous. On Thursday, astronomers who are conducting what they describe as the biggest and most precise survey yet of the history of the universe announced that they might have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, the mysterious force that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos.

On Thursday, astronomers who are conducting what they describe as the biggest and most precise survey yet of the history of the universe announced that they might have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, the mysterious force that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos. Even though more people will cast a ballot in 2024 than any previous year, the prevailing mood seems more fearful than celebratory. In the words of Darrell M. West, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, the combination of online influence campaigns and artificial intelligence has created a “

Even though more people will cast a ballot in 2024 than any previous year, the prevailing mood seems more fearful than celebratory. In the words of Darrell M. West, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, the combination of online influence campaigns and artificial intelligence has created a “