Category: Archives

On Percival Everett

Leo Robson at the LRB:

No American novelist has devoted as much energy as Percival Everett to the proper noun, its powers as engine, instrument and index. Towards the end of Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (first published in 2013), a story about storytelling in which nobody is called Percival Everett or Virgil Russell, one of the narrators gives a list of 516 gerunds that encompass the whole of human activity. ‘Naming’ appears first and last – and seventeen times in-between. Everett’s first novel, Suder (1983), ends with the main character, a baseball player in a terminal slump, uttering the words ‘Craig Suder’. The hero of I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009) goes through life being called ‘Not Sidney’, and battles with his resulting inclination towards passivity and victimhood. Everett has expressed opposition to labels, categories and genres. ‘I never think in regions,’ he said, during an interview for a book about writers from the American South. Once something is named, its potential is limited, its freedom compromised. In Percival Everett by Virgil Russell, a father-to-be tries to persuade his wife to leave their son unnamed in order to spare the child ridicule. (‘You can’t mess up ———.’) The painter in So Much Blue (2017) has spoken the title of his long-gestating work-in-progress just once ‘under my breath while I was alone in my studio’ and fears that his children ‘might try to name it and so ruin it and everything’.

No American novelist has devoted as much energy as Percival Everett to the proper noun, its powers as engine, instrument and index. Towards the end of Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (first published in 2013), a story about storytelling in which nobody is called Percival Everett or Virgil Russell, one of the narrators gives a list of 516 gerunds that encompass the whole of human activity. ‘Naming’ appears first and last – and seventeen times in-between. Everett’s first novel, Suder (1983), ends with the main character, a baseball player in a terminal slump, uttering the words ‘Craig Suder’. The hero of I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009) goes through life being called ‘Not Sidney’, and battles with his resulting inclination towards passivity and victimhood. Everett has expressed opposition to labels, categories and genres. ‘I never think in regions,’ he said, during an interview for a book about writers from the American South. Once something is named, its potential is limited, its freedom compromised. In Percival Everett by Virgil Russell, a father-to-be tries to persuade his wife to leave their son unnamed in order to spare the child ridicule. (‘You can’t mess up ———.’) The painter in So Much Blue (2017) has spoken the title of his long-gestating work-in-progress just once ‘under my breath while I was alone in my studio’ and fears that his children ‘might try to name it and so ruin it and everything’.

more here.

Bears In The Villa

John Last at The New Atlantis:

Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state, brown bears were hunted nearly to extinction — by the mid-1990s, just four were counted in the region around Trento, where Papi was killed.

Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state, brown bears were hunted nearly to extinction — by the mid-1990s, just four were counted in the region around Trento, where Papi was killed.

For the past twenty-some years, however, an E.U.-funded program called Life Ursus has imported brown bears to Northern Italy to boost the region’s number of breeding pairs, taking candidates from its eastern neighbor Slovenia, where forests less pressed upon by human activity are still capable of sheltering a reasonably healthy bear population.

Though the program has undoubtedly succeeded in its aim — the brown bear population is now estimated at over 100 in the region — it has not been without controversy.

more here.

Slavoj Žižek & Ash Sarkar – In Conversation

We’ve Had Great Success Extending Life. What About Ending It?

Brooke Jarvis in The New Yorker:

In “Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer” (Riverhead), Steven Johnson credits John Graunt with creating history’s first “life table”—using death data to predict how many years of remaining life a given person could expect. (One Dutch contemporary, a proto-actuary, took Graunt’s tables a bit too literally, writing confidently to his brother, “You will live to until about the age of 56 and a half. And I until 55.”) In fact, Graunt’s estimates were more of a guess than a calculation: when he wrote his treatise, in the sixteen-sixties, the Bills of Mortality didn’t record people’s age at death, and they wouldn’t for another half century. Yet his guesses about survival rates for different age groups turned out to be remarkably accurate in describing not just London at the time but humanity as a whole. For most of our long history as a species, our average life expectancy was capped at about thirty-five years.

In “Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer” (Riverhead), Steven Johnson credits John Graunt with creating history’s first “life table”—using death data to predict how many years of remaining life a given person could expect. (One Dutch contemporary, a proto-actuary, took Graunt’s tables a bit too literally, writing confidently to his brother, “You will live to until about the age of 56 and a half. And I until 55.”) In fact, Graunt’s estimates were more of a guess than a calculation: when he wrote his treatise, in the sixteen-sixties, the Bills of Mortality didn’t record people’s age at death, and they wouldn’t for another half century. Yet his guesses about survival rates for different age groups turned out to be remarkably accurate in describing not just London at the time but humanity as a whole. For most of our long history as a species, our average life expectancy was capped at about thirty-five years.

Johnson calls this phenomenon “the long ceiling.”

More here.

To Live Past 100, Mangia a Lot Less: Italian Expert’s Ideas on Aging

Jason Horowitz in The New York Times:

Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

Now, decades after Dr. Longo dropped his grunge-era band, DOT, for a career in biochemistry, the Italian professor stands with his floppy rocker hair and lab coat at the nexus of Italy’s eating and aging obsessions. “For studying aging, Italy is just incredible,” said Dr. Longo, a youthful 56, at the lab he runs at a cancer institute in Milan, where he will speak at an aging conference later this month. Italy has one of the world’s oldest populations, including multiple pockets of centenarians who tantalize researchers searching for the fountain of youth. “It’s nirvana.” Dr. Longo, who is also a professor of gerontology and director of the U.S.C. Longevity Institute in California, has long advocated longer and better living through eating Lite Italian, one of a global explosion of Road to Perpetual Wellville theories about how to stay young in a field that is itself still in its adolescence.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

The Sum of Life

Nothing to do but work,

…. Nothing to eat but food,

Nothing to wear but clothes

…. To keep one from going nude.

Nothing to breathe but air,

…. Quick as a flash it’s gone;

Nowhere to fall but off,

…. Nowhere to stand but on.

………… . . . . . . . . . .

Nothing to sing but songs,

…. Ah, well, alas! alack!

Nowhere to go but out,

…. Nowhere to come but back.

…………. . . . . . . . . .

Nothing to strike but a gait;

…. Everything moves that goes.

Nothing at all but common sense

…. can ever withstand these woes.

by Benjamin Franklin King, Jr. (1857-1894)

from Confucius to Cummings

New Direction Books, 1964

Sunday, March 24, 2024

Nobel Laureate, Angus Deaton: Rethinking My Economics

Angus Deaton at the website of the IMF:

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right.

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right.

Like many others, I have recently found myself changing my mind, a discomfiting process for someone who has been a practicing economist for more than half a century. I will come to some of the substantive topics, but I start with some general failings.

More here.

The Extraordinary Life and Work of Frans de Waal

Lawrence M. Krauss in Quillette:

Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center.

Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center.

His passing is a loss not just for his family and friends, but for science and society more broadly. De Waal’s death ends a career that showed what science can accomplish at its very best, by changing our perspective on ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

Frans was more than just a colleague and friend to me. He was a teacher. I count myself among the innumerable people who were impacted by his writing and lecturing in clear and explicit ways.

That is why I don’t feel that it is inappropriate for me to pen this brief memorial, even though I am a theoretical physicist and Frans was a primatologist.

More here.

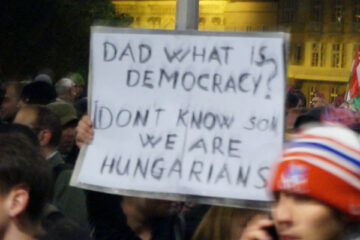

On Hungary and the strange bedfellows of anti-refugeeism

Holly Case in the Boston Review:

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Anyone who has followed the serpentine trajectory of Hungarian politics since the controlled collapse of state socialism in 1989 might be forgiven for throwing their hands up in confusion. For more than two and a half decades, Hungarian political life has been a story of reversals.

More here.

Maniza Naqvi on Saving Karachi’s Oldest Bookstore

Maniza Naqvi at Literary Hub:

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

I came from Pakistan thirty years ago for my job. I absolutely love my job. I get to work with national and local governments and villages to build social safety nets in order to reduce poverty. I get to design and supervise projects. I don’t actually do anything with my own hands, but I’m on the ground in many different countries, and I travel a lot. And now—as if flying while Muslim wasn’t fun enough—they’re going to ban me too?

I feel scattered all over the map. My writing helps to ground me. But still, I feel like I need a change. I need someone to throw me a lifeline.

More here.

The Keys to a Long Life Are Sleep and a Better Diet—and Money

Matt Reynolds in Wired:

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

Today’s elite take life-extension a lot more literally. Skipping neatly over the matter of Bryan Johnson’s nightly penis rejuvenation regime, billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel are sinking big money into the prospect of therapies to extend our mortal lives.

But how would one do that exactly? In his new book, Why We Die, Nobel Prize–winning biologist Venki Ramakrishnan breaks down the biology of aging to examine what potential humankind really has for life extension.

More here.

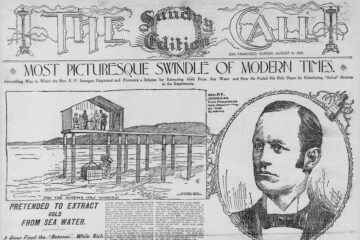

Eleven of the greatest scientific hoaxes

Eleanor Harris in New Scientist:

CRAP paper accepted by journal

CRAP paper accepted by journal

At New Scientist we love a good hoax, especially one that both amuses and makes a serious point about the communication of science. So kudos to Philip Davis, a graduate student at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who got a nonsensical computer-generated paper accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

The Sokal hoax

In 1996, American physicist Alan Sokal submitted a paper loaded with nonsensical jargon to the journal Social Text, in which he argued that quantum gravity is a social and linguistic construct. (Read Sokal’s paper). When the journal published it, Sokal revealed that the paper was in fact a spoof. The incident triggered a storm of debate about the ethics of Sokal’s prank.

More here.

Sunday Poem

“Damn!”

Sometimes he’d be washing the car

. . . all by himself|

and he’d say, “Damn!”

or sweeping the last dry morsels of leaves

onto an old dust pan

saved just for outside

for when he was alone

in the silence of a summer afternoon

he’d say, “Damn!”

He didn’t go to his aubuelita’s funeral

He wasn’t there when his father died

He was with someone else he loved,

and he wasn’t there the moment she died

Y le pesaba, sabes?

An anvil of loneliness

would fall into his chest

and he’d say, “Damn!”

by César A Gonzalez

from Paper Dance, 55 Latino Poets

Persea Books, 1995

Y le pesaba, sabes?: and it weighed on him, you know?

Paulin Hountondji (1942 – 2024) Philosopher And Politician

Frans de Waal (1948 – 2024) Primatologist And Ethologist

Lyn Hejinian (1941 – 2024) Poet Associated With ‘Language Poets’

Saturday, March 23, 2024

Carlo Rovelli on White Holes

An Exquisite Biography of a Gilded Age Legend

Megan O’Grady at the New York Times:

Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much.

Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much.

Belle, as she was known, thought nothing of bringing home lion cubs from the zoo to show off at teatime, or of taking a younger lover. The necklines of her couture dresses were low; her trademark rope of pearls — a gift from her devoted (and long-suffering) husband — hung nearly to her knees. Society columnists struck a tone of derisive admiration: One 1894 profile marveled at Gardner’s magnetism, given that her face was “almost destitute of those lines of beauty” appreciated at the time.

more here.

The Virtue of Slow Writers

Lauren Alwan at The Millions:

The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published Middlesex, Dwight Garner wrote in The New York Times, “It has been a long, lonely vigil. We’d nearly forgotten he was out there.” Garner’s 2011 article, “Dear Important Novelists: Be Less Like Moses and More Like Howard Cosell,” argues the “long gestation period” among the period’s young writers (Middlesex was written over nine) marks “a desalinating tidal change in the place novelists occupy in our culture.” The writer, hidden away in monkish solitude, is no longer a commentator on events of the moment in the vein of, say, Saul Bellow. Bellow wrote four massive books in 11 years, and in doing so, Garner says, “snatched control, with piratical confidence and a throbbing id, of American literature’s hive mind.” Comparing Eugenides’s books, he notes, “So much time elapses between them that his image in dust-jacket photographs can change alarmingly.” Write slowly and not only do you risk being forgotten, you may no longer be recognizable.

The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published Middlesex, Dwight Garner wrote in The New York Times, “It has been a long, lonely vigil. We’d nearly forgotten he was out there.” Garner’s 2011 article, “Dear Important Novelists: Be Less Like Moses and More Like Howard Cosell,” argues the “long gestation period” among the period’s young writers (Middlesex was written over nine) marks “a desalinating tidal change in the place novelists occupy in our culture.” The writer, hidden away in monkish solitude, is no longer a commentator on events of the moment in the vein of, say, Saul Bellow. Bellow wrote four massive books in 11 years, and in doing so, Garner says, “snatched control, with piratical confidence and a throbbing id, of American literature’s hive mind.” Comparing Eugenides’s books, he notes, “So much time elapses between them that his image in dust-jacket photographs can change alarmingly.” Write slowly and not only do you risk being forgotten, you may no longer be recognizable.

more here.