Rebecca Panovka at Bookforum:

IN THE FALL OF 1866, FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY FOUND HIMSELF barreling toward every writer’s worst nightmare: a deadline he couldn’t ignore. Having signed an ill-advised contract to avoid a trip to debtor’s prison, he now owed the publisher Fyodor Stellovsky a new novel of at least 160 pages by November 1. If he failed to deliver, Stellovsky would be entitled to publish whatever Dostoyevsky wrote over the next nine years free of charge. A more practical man might have spent his summer on the project for Stellovsky, but Dostoyevsky was simultaneously preparing segments of Crime and Punishment for serialization, and his plan to write one novel in the morning and another at night hadn’t panned out. By the beginning of October, he had not produced a single page of the promised novel. Staring down the literary equivalent of indentured servitude, he decided to try a new method to pick up the pace: hiring a stenographer and writing by dictation.

more here.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture. Researchers with the

Researchers with the  “P

“P The

The

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes?

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes? IN OSAKA, JAPAN,

IN OSAKA, JAPAN, In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by

In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by  There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by

There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by  Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated.

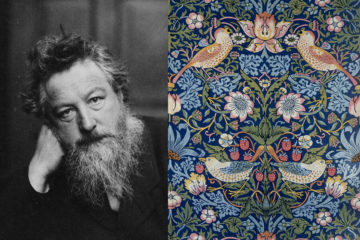

Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated. Behind the exquisite floral wallpaper lurks a social reformer. British designer William Morris (1834-96) is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. He sought nothing less than to overturn what he considered the deleterious effects of industrialization on Victorian society. And his artistic influence continues today, not only at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution he helped shape, but also as inspiration to contemporary artists.

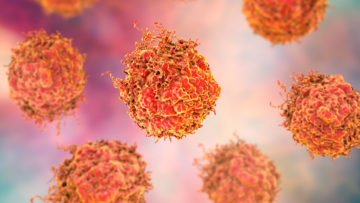

Behind the exquisite floral wallpaper lurks a social reformer. British designer William Morris (1834-96) is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. He sought nothing less than to overturn what he considered the deleterious effects of industrialization on Victorian society. And his artistic influence continues today, not only at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution he helped shape, but also as inspiration to contemporary artists. Underground creepy crawly state. Bosom malignancy. Sun oriented force. These might sound like expressions from a work of fiction, but they are actually strange translations, pulled from the scholarly literature, of scientific terms — ant colony, breast cancer and solar energy, respectively. Guillaume Cabanac, a computer scientist at the University of Toulouse, France, spots such bizarre phrases in academic papers every day.

Underground creepy crawly state. Bosom malignancy. Sun oriented force. These might sound like expressions from a work of fiction, but they are actually strange translations, pulled from the scholarly literature, of scientific terms — ant colony, breast cancer and solar energy, respectively. Guillaume Cabanac, a computer scientist at the University of Toulouse, France, spots such bizarre phrases in academic papers every day. About 30 minutes into his new concert film Blackalachia,

About 30 minutes into his new concert film Blackalachia,  Of course, he was looking for love. Aren’t we all? And he seemed to be looking for it in all the right places—namely, the southern coastal counties of California, where he was, literally, the lone wolf, with seemingly no male competitors at all. In fact, OR-93 (2019-2021) was the first gray wolf to appear in the region for two or three hundred years. The absence of rivals was good news for him, but the rest of the equation was hopeless, because there were apparently no female counterparts for him to encounter there, either—no one to meet and mate with. To be honest, OR-93’s journey from his birthplace, in Oregon, to California was reproductively doomed from the start. He could have crossed party lines with a wayward labradoodle or a lusty mountain

Of course, he was looking for love. Aren’t we all? And he seemed to be looking for it in all the right places—namely, the southern coastal counties of California, where he was, literally, the lone wolf, with seemingly no male competitors at all. In fact, OR-93 (2019-2021) was the first gray wolf to appear in the region for two or three hundred years. The absence of rivals was good news for him, but the rest of the equation was hopeless, because there were apparently no female counterparts for him to encounter there, either—no one to meet and mate with. To be honest, OR-93’s journey from his birthplace, in Oregon, to California was reproductively doomed from the start. He could have crossed party lines with a wayward labradoodle or a lusty mountain