Amy Maxmen in Nature:

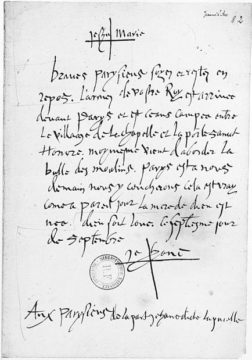

The head is stately, calm, and wise,

And bears a princely part;

And down below in secret lies

The warm, impulsive heart.

— John Godfrey Saxe, 1898

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection.

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection.

In the past 15 years, scientists have uncovered a developmental link between the two. In 2010, for example, researchers revealed that the same small pool of cells that divides and differentiates to form the heart in mouse embryos also gives way to muscles in their throats and lower heads1. Key components of the two are cut from the same cloth.

Even more surprising is that the embryonic head–heart connection pre-dates the evolutionary origin of vertebrates, and perhaps even of the head itself. Researchers stumbled on the link while studying sea squirts, blobby, sedentary marine creatures, found affixed to the sea floor, that have two openings — one for sucking water in and the other for squirting it out — hence the name.

More here.

On a Wednesday morning in January,

On a Wednesday morning in January,  My friend Agnes Callard

My friend Agnes Callard  Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough.

Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough. Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment.

Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment. The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

W

W Y

Y Laura Kipnis in LitHub:

Laura Kipnis in LitHub: Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books:

Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books: Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate:

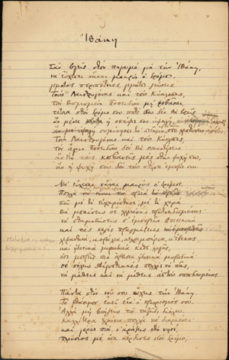

Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate: How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller.

How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller. In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

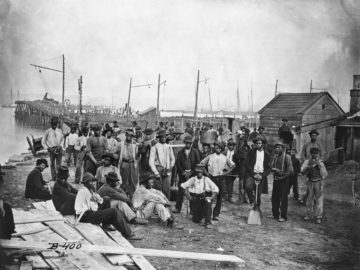

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or