William Thomas III in The New York Times:

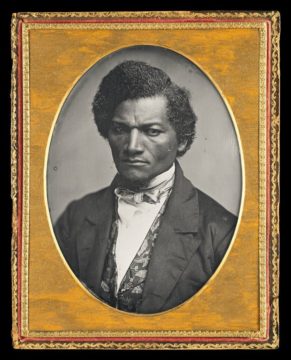

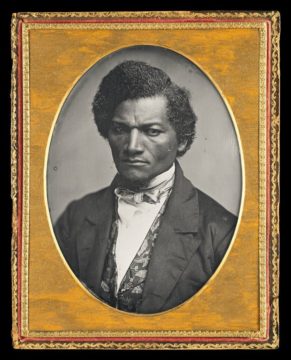

On Aug. 6, 1845, Frederick Douglass set sail on a speaking tour of England and Ireland to promote the cause of antislavery. He had just published “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” an instant best seller that, along with his powerful oratory, had made him a celebrity in the growing abolition movement. No sooner had he arrived in Britain, however, than Douglass began to realize that white abolitionists in Boston had been working to undermine him: Before he’d even left American shores, they had privately written his British hosts and impugned his motives and character.

On Aug. 6, 1845, Frederick Douglass set sail on a speaking tour of England and Ireland to promote the cause of antislavery. He had just published “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” an instant best seller that, along with his powerful oratory, had made him a celebrity in the growing abolition movement. No sooner had he arrived in Britain, however, than Douglass began to realize that white abolitionists in Boston had been working to undermine him: Before he’d even left American shores, they had privately written his British hosts and impugned his motives and character.

The author of these “sneaky,” condescending missives, Douglass soon discovered, was Maria Weston Chapman, a wealthy, well-connected and dedicated activist whose scornful nickname, “the Contessa,” stemmed from her imperious behind-the-scenes work with the leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. In Linda Hirshman’s fresh, provocative and engrossing account of the abolition movement, Chapman was “the prime mover” in driving Douglass away from the avowedly nonpolitical Garrisonians and toward the overtly political wing of abolitionism led by Gerrit Smith, a wealthy white businessman in upstate New York. With brisk, elegant prose Hirshman lays bare “the casual racism of the privileged class” within Garrison’s abolitionist circle.

Setting out on her research, Hirshman initially considered Chapman a feminist hero whose significant role in the movement had long been overlooked. After all, Chapman raised enormous funds for abolition societies, edited Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, for years in his long absences, and carried on a massive petition campaign to end slavery. But when she read Chapman’s voluminous correspondence, Hirshman encountered the ugly personal rivalries and private politics at the center of a shaky alliance between the uncompromising Garrison and the ambitious and self-possessed Douglass.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

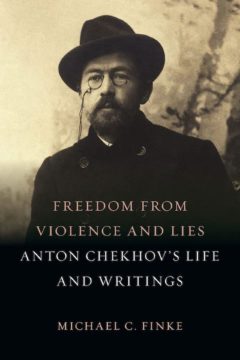

Chekhov is easier to know and read than the other Russian giants. He doesn’t look big or talk big. He’s funny on purpose. He shows us how to read him; he quietly attunes us to place and situation. We observe more than judge his characters’ actions; we detect their mental and emotional states through their physical symptoms. Chekhov began his professional career as a writer while in medical school. Even as he imagined the agitations and disruptions and occasional explosions of his characters, he was always also a doctor. He describes what it feels like to fall in love, to be pregnant and to miscarry, to bully one’s children, to flutter about helplessly while seeking someone to love, to have typhus, to cringe with embarrassment over a bespattering sneeze, to blather like a professor, to be struck dumb by love, to beg for sympathy, to grieve, to menace the innocent, to be conscious of but prey to one’s weaknesses, to be overworked to the point of hallucinating, to be ruthless.

Chekhov is easier to know and read than the other Russian giants. He doesn’t look big or talk big. He’s funny on purpose. He shows us how to read him; he quietly attunes us to place and situation. We observe more than judge his characters’ actions; we detect their mental and emotional states through their physical symptoms. Chekhov began his professional career as a writer while in medical school. Even as he imagined the agitations and disruptions and occasional explosions of his characters, he was always also a doctor. He describes what it feels like to fall in love, to be pregnant and to miscarry, to bully one’s children, to flutter about helplessly while seeking someone to love, to have typhus, to cringe with embarrassment over a bespattering sneeze, to blather like a professor, to be struck dumb by love, to beg for sympathy, to grieve, to menace the innocent, to be conscious of but prey to one’s weaknesses, to be overworked to the point of hallucinating, to be ruthless. Paul Farmer, a physician, anthropologist and humanitarian who gained global acclaim for his work delivering high-quality health care to some of the world’s poorest people, died on Monday on the grounds of a hospital and university he had helped establish in Butaro, Rwanda. He was 62.

Paul Farmer, a physician, anthropologist and humanitarian who gained global acclaim for his work delivering high-quality health care to some of the world’s poorest people, died on Monday on the grounds of a hospital and university he had helped establish in Butaro, Rwanda. He was 62. Black humanity is unexceptional, Walter Johnson exhorts. Once we have taken up the debate of humanization versus dehumanization under slavery, we have already ceded critical ground. Like Johnson, midcentury Black Power activists understood that it was necessary to redirect such questions toward the matter of how the legacy of racial slavery continues to shape citizenship, democratic participation, and human rights, not just for black Americans but for people of color around the globe. Johnson’s essay offers profitable avenues for reappraising how Black Power is the conceptual bridge between Reconstruction-era black struggles for self-determination and Black Lives Matter’s present-day fight to end martial and economic violence against people of color.

Black humanity is unexceptional, Walter Johnson exhorts. Once we have taken up the debate of humanization versus dehumanization under slavery, we have already ceded critical ground. Like Johnson, midcentury Black Power activists understood that it was necessary to redirect such questions toward the matter of how the legacy of racial slavery continues to shape citizenship, democratic participation, and human rights, not just for black Americans but for people of color around the globe. Johnson’s essay offers profitable avenues for reappraising how Black Power is the conceptual bridge between Reconstruction-era black struggles for self-determination and Black Lives Matter’s present-day fight to end martial and economic violence against people of color. In 1975, Finnissy witnessed Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter

In 1975, Finnissy witnessed Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter

The biggest argument I’ve ever witnessed was about whether men had landed on the moon. Some years ago, at dinner—paella and wine—a chemist with a Ph.D. from Stanford suggested that the moon landing had been a hoax. This did not go over well with his father-in-law at the head of the table. At first I didn’t understand what I was hearing—I didn’t know then how many people believe the moon landing to be a fiction. Soon the men were roaring, the chemist’s brother-in-law got involved: “Of all the boneheaded bullshit to come pouring out of your face …” “Well, how do you explain …” Threats were flung, neck veins swelling, a hand slammed on the table, a knife clattered to the floor. We joked about it recently, the brother-in-law and I, recalling the scene, eating pasta with clams and garlic, and he asked me, “You’ve read the Apollo 11 eulogy speech, right?” I hadn’t. “Read it,” he said.

The biggest argument I’ve ever witnessed was about whether men had landed on the moon. Some years ago, at dinner—paella and wine—a chemist with a Ph.D. from Stanford suggested that the moon landing had been a hoax. This did not go over well with his father-in-law at the head of the table. At first I didn’t understand what I was hearing—I didn’t know then how many people believe the moon landing to be a fiction. Soon the men were roaring, the chemist’s brother-in-law got involved: “Of all the boneheaded bullshit to come pouring out of your face …” “Well, how do you explain …” Threats were flung, neck veins swelling, a hand slammed on the table, a knife clattered to the floor. We joked about it recently, the brother-in-law and I, recalling the scene, eating pasta with clams and garlic, and he asked me, “You’ve read the Apollo 11 eulogy speech, right?” I hadn’t. “Read it,” he said.

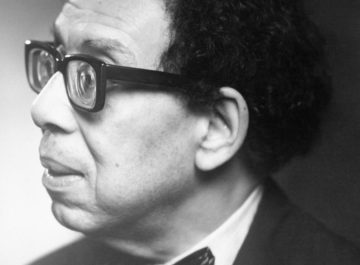

JARVIS GIVENS

JARVIS GIVENS On Aug. 6, 1845, Frederick Douglass set sail on a speaking tour of England and Ireland to promote the cause of antislavery. He had just published “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” an instant best seller that, along with his powerful oratory, had made him a celebrity in the growing abolition movement. No sooner had he arrived in Britain, however, than Douglass began to realize that white abolitionists in Boston had been working to undermine him: Before he’d even left American shores, they had privately written his British hosts and impugned his motives and character.

On Aug. 6, 1845, Frederick Douglass set sail on a speaking tour of England and Ireland to promote the cause of antislavery. He had just published “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” an instant best seller that, along with his powerful oratory, had made him a celebrity in the growing abolition movement. No sooner had he arrived in Britain, however, than Douglass began to realize that white abolitionists in Boston had been working to undermine him: Before he’d even left American shores, they had privately written his British hosts and impugned his motives and character. Angela

Angela

A few years ago, an older colleague of mine passed away. I spent some time with his widow in the months afterward. As a prominent sleep researcher, her husband had traveled quite often to attend academic conferences. Over dinner one night, she shook her head as she told me it just did not feel like he was gone. It felt as though he was just away on another trip and would walk through their door again at any minute.

A few years ago, an older colleague of mine passed away. I spent some time with his widow in the months afterward. As a prominent sleep researcher, her husband had traveled quite often to attend academic conferences. Over dinner one night, she shook her head as she told me it just did not feel like he was gone. It felt as though he was just away on another trip and would walk through their door again at any minute. Like everyone, we at Scientific American have been thinking about this terrible disease constantly and trying to make sense of it. We’ve published hundreds of articles about the

Like everyone, we at Scientific American have been thinking about this terrible disease constantly and trying to make sense of it. We’ve published hundreds of articles about the