Liz Mineo in Harvard Gazette:

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

GAZETTE: Carter G. Woodson is known as the father of Black history. How did his life inform his development as a teacher, thinker, and scholar?

GIVENS: It’s always important to start with the fact that Carter G. Woodson was both the child and the student of formerly enslaved people before we emphasize that in 1912, he became the second Black person to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard. He was born in 1875 and grew up working on his family’s farm. His first teachers were his formerly enslaved uncles who taught him in a one-room schoolhouse in Buckingham County, Virginia. He worked in the coal mines before he started high school at the age of 20 and worked alongside formerly enslaved men and Civil War veterans who were illiterate, men who relied on Woodson to read to them in the evenings. It was in those experiences that Woodson came to learn that Black people carried important knowledge from their lived experiences that needed to be taken seriously and preserved. In 1915, he created the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History while he worked as a teacher during Jim Crow, and then went on to become the man that people refer to as the “father of Black history.” As an educator and institution-builder Woodson popularized Black history and celebrated the contributions of Black people in American history, and as a scholar, his books indicted the American school system for the various forms of violence it inflicted upon Black people.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

If the great campaigners for free speech of the past, such as Baruch Spinoza or Mary Wollstonecraft or Frederick Douglass, were alive today, “they would surely declare the 21st century an unprecedented golden age”. So suggests Jacob Mchangama in his

If the great campaigners for free speech of the past, such as Baruch Spinoza or Mary Wollstonecraft or Frederick Douglass, were alive today, “they would surely declare the 21st century an unprecedented golden age”. So suggests Jacob Mchangama in his  In a time

In a time Do laws criminalizing prostitution violate the Constitution? Probably. Until recently, such a proposition would have been as absurd as

Do laws criminalizing prostitution violate the Constitution? Probably. Until recently, such a proposition would have been as absurd as

“If a fat person behaves badly in an artistic context, then they are doubly misbehaving. Being fat is a transgression in itself. . . . An obese person’s simple existence constitutes misbehaving,” Susiraja once remarked in an interview. The impropriety she mentions runs rampant throughout her self-portraiture. Part of this is fueled by her talent for turning commonplace items—food, toys, women’s shoes, boring underwear—into uncanny and even oddly visceral props. Take Happy Meal, 2011, in which various lengths of apple peel delicately grace the top of the artist’s plump bare foot, calling to mind old scabs, skin ulcers; or Let’s Call, 2016, a picture of Susiraja hunched over, an orange rotary telephone shoved between her legs and trapped in the crotch of a hideous pair of pantyhose that have been pulled down around her knees. The phone makes me think of a miscarried infant—the long, coiled cord of the handset, which is draped over the artist’s neck, feels more than a little umbilical.

“If a fat person behaves badly in an artistic context, then they are doubly misbehaving. Being fat is a transgression in itself. . . . An obese person’s simple existence constitutes misbehaving,” Susiraja once remarked in an interview. The impropriety she mentions runs rampant throughout her self-portraiture. Part of this is fueled by her talent for turning commonplace items—food, toys, women’s shoes, boring underwear—into uncanny and even oddly visceral props. Take Happy Meal, 2011, in which various lengths of apple peel delicately grace the top of the artist’s plump bare foot, calling to mind old scabs, skin ulcers; or Let’s Call, 2016, a picture of Susiraja hunched over, an orange rotary telephone shoved between her legs and trapped in the crotch of a hideous pair of pantyhose that have been pulled down around her knees. The phone makes me think of a miscarried infant—the long, coiled cord of the handset, which is draped over the artist’s neck, feels more than a little umbilical. One day, as a small boy, I was copying the portrait of Napoleon. His left eye was giving me trouble. Already I had erased the drawing of it several times. My father leaned over and lovingly corrected my work. I threw the paper and pencil across the room, saying “now it is your drawing, not mine.” Two cannot make a single drawing. I am sure the most skillful imitation can be detected by the originator. The sheer delight in the act of drawing has its way in the drawing and that also is a quality that the imitator can’t imitate. The personal abstraction, the rapport between subject and the thought also are unimitatable.

One day, as a small boy, I was copying the portrait of Napoleon. His left eye was giving me trouble. Already I had erased the drawing of it several times. My father leaned over and lovingly corrected my work. I threw the paper and pencil across the room, saying “now it is your drawing, not mine.” Two cannot make a single drawing. I am sure the most skillful imitation can be detected by the originator. The sheer delight in the act of drawing has its way in the drawing and that also is a quality that the imitator can’t imitate. The personal abstraction, the rapport between subject and the thought also are unimitatable. From the moment it appeared in April 1903, The Souls of Black Folk caused a sensation. Among black readers,

From the moment it appeared in April 1903, The Souls of Black Folk caused a sensation. Among black readers,  The recent

The recent  Modern particle physics is a victim of its own success. We have extremely good theories — so good that it’s hard to know exactly how to move beyond them, since they agree with all the experiments. Yet, there are strong indications from theoretical considerations and cosmological data that we need to do better. But the leading contenders, especially supersymmetry, haven’t yet shown up in our experiments, leading some to wonder whether anthropic selection is a better answer. Michael Dine gives us an expert’s survey of the current situation, with pointers to what might come next.

Modern particle physics is a victim of its own success. We have extremely good theories — so good that it’s hard to know exactly how to move beyond them, since they agree with all the experiments. Yet, there are strong indications from theoretical considerations and cosmological data that we need to do better. But the leading contenders, especially supersymmetry, haven’t yet shown up in our experiments, leading some to wonder whether anthropic selection is a better answer. Michael Dine gives us an expert’s survey of the current situation, with pointers to what might come next. “Can you see me?” In the age of video calls, this has become a common question. But when posed to philosopher David Chalmers, it takes on a deeper significance. Regarding the basic version of virtual reality (VR) in which we’re having our conversation, Chalmers suggests that “some very conservative philosophers would say no, I am merely seeing a pattern of pixels on a screen and I’m not seeing you behind it.” But Chalmers has a different view: “Yes, I’m seeing you perfectly,” he replies, covering both meanings with his answer. His seemingly simple claim has implications not just for the possibilities of virtual reality, but the nature of actual reality, too.

“Can you see me?” In the age of video calls, this has become a common question. But when posed to philosopher David Chalmers, it takes on a deeper significance. Regarding the basic version of virtual reality (VR) in which we’re having our conversation, Chalmers suggests that “some very conservative philosophers would say no, I am merely seeing a pattern of pixels on a screen and I’m not seeing you behind it.” But Chalmers has a different view: “Yes, I’m seeing you perfectly,” he replies, covering both meanings with his answer. His seemingly simple claim has implications not just for the possibilities of virtual reality, but the nature of actual reality, too. Lee wanted to make Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as a movie that was by China, for China, while the country was at this turning point. But though it was embraced around the world, it failed to meet that criterion of the holy grail production, since it was of little interest to audiences in China. There, moviegoers were watching True Lies because it was the kind of action-packed spectacular their own country’s filmmakers couldn’t produce. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had seemed so novel in America, was old hat to Chinese moviegoers reared on kung fu.

Lee wanted to make Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as a movie that was by China, for China, while the country was at this turning point. But though it was embraced around the world, it failed to meet that criterion of the holy grail production, since it was of little interest to audiences in China. There, moviegoers were watching True Lies because it was the kind of action-packed spectacular their own country’s filmmakers couldn’t produce. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had seemed so novel in America, was old hat to Chinese moviegoers reared on kung fu. S

S

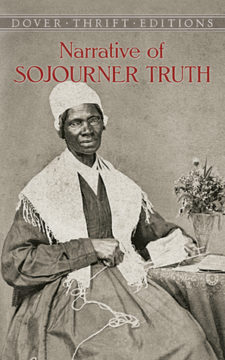

One of the most famous and admired African-American women in U.S. history, Sojourner Truth sang, preached, and debated at camp meetings across the country, led by her devotion to the antislavery movement and her ardent pursuit of women’s rights. Born into slavery in 1797, Truth fled from bondage some 30 years later to become a powerful figure in the progressive movements reshaping American society.

One of the most famous and admired African-American women in U.S. history, Sojourner Truth sang, preached, and debated at camp meetings across the country, led by her devotion to the antislavery movement and her ardent pursuit of women’s rights. Born into slavery in 1797, Truth fled from bondage some 30 years later to become a powerful figure in the progressive movements reshaping American society. Since the declaration of Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s birthday as a federal holiday, our country has celebrated the civil-rights movement, valorizing its tactics of nonviolence as part of our national narrative of progress toward a more perfect union. Yet we rarely ask about the short life span of those tactics. By 1964, nonviolence seemed to have run its course, as Harlem and Philadelphia ignited in flames to protest police brutality, poverty, and exclusion, in what were denounced as riots. Even larger and more destructive uprisings followed, in Los Angeles and Detroit, and, after the assassination of King, in 1968, across the country: a fiery tumult that came to be seen as emblematic of Black urban violence and poverty. The violent turn in Black protest was condemned in its own time and continues to be lamented as a tragic retreat from the noble objectives and demeanor of the church-based Southern movement.

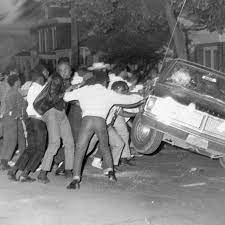

Since the declaration of Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s birthday as a federal holiday, our country has celebrated the civil-rights movement, valorizing its tactics of nonviolence as part of our national narrative of progress toward a more perfect union. Yet we rarely ask about the short life span of those tactics. By 1964, nonviolence seemed to have run its course, as Harlem and Philadelphia ignited in flames to protest police brutality, poverty, and exclusion, in what were denounced as riots. Even larger and more destructive uprisings followed, in Los Angeles and Detroit, and, after the assassination of King, in 1968, across the country: a fiery tumult that came to be seen as emblematic of Black urban violence and poverty. The violent turn in Black protest was condemned in its own time and continues to be lamented as a tragic retreat from the noble objectives and demeanor of the church-based Southern movement.