Category: Archives

Basilica di San Francesco d’Assisi

Cynthia Zarin at The Paris Review:

For a number of weeks one spring, I spent every afternoon at the Basilica di San Francesco d’Assisi. It was what we then thought was the tail end of a plague, and I had come to Italy to visit a friend who had lived for many years a few kilometers above Assisi, in an old schoolhouse. This turned out not to be the visit I had imagined, nor, I am sure, the one she had, and after a few weeks, I went to Rome. But before that, every afternoon, I drove down into town—I had rented a car—past the long flank of Monte Subasio, with its temperate oxen, parked on the escarpment before the gates because the switchback of tiny streets flummoxed me, and walked down to the basilica. Everything was off-kilter, as if a great wave had passed over us, and now, if we were lucky to be alive, we found ourselves stranded on the banks of our own lives or paddling furiously toward where we imagined the shore might be. I had been to the basilica and to Assisi many times over the years to visit my friend, and so I knew my way on the small strade that opened and closed into a series of piazze, as if the town had exhaled and then drawn breath again.

For a number of weeks one spring, I spent every afternoon at the Basilica di San Francesco d’Assisi. It was what we then thought was the tail end of a plague, and I had come to Italy to visit a friend who had lived for many years a few kilometers above Assisi, in an old schoolhouse. This turned out not to be the visit I had imagined, nor, I am sure, the one she had, and after a few weeks, I went to Rome. But before that, every afternoon, I drove down into town—I had rented a car—past the long flank of Monte Subasio, with its temperate oxen, parked on the escarpment before the gates because the switchback of tiny streets flummoxed me, and walked down to the basilica. Everything was off-kilter, as if a great wave had passed over us, and now, if we were lucky to be alive, we found ourselves stranded on the banks of our own lives or paddling furiously toward where we imagined the shore might be. I had been to the basilica and to Assisi many times over the years to visit my friend, and so I knew my way on the small strade that opened and closed into a series of piazze, as if the town had exhaled and then drawn breath again.

more here.

An optimist’s guide to the future: the economist who believes that human ingenuity will save the world

David Shariatmadari in The Guardian:

Why is the Anglo-Saxon world so individualistic, and why has China leaned towards collectivism? Was it Adam Smith, or the Bill of Rights; communism and Mao? According to at least one economist, there might be an altogether more surprising explanation: the difference between wheat and rice. You see, it’s fairly straightforward for a lone farmer to sow wheat in soil and live off the harvest. Rice is a different affair: it requires extensive irrigation, which means cooperation across parcels of land, even centralised planning. A place where wheat grows favours the entrepreneur; a place where rice grows favours the bureaucrat.

The influence of the “initial conditions” that shape societies’ development is what Oded Galor has been interested in for the past 40 years. He believes they reverberate across millennia and even seep into what we might think of as our personalities. Whether or not you have a “future-oriented mindset” – in other words, how much money you save and how likely you are to invest in your education – can, he argues, be partly traced to what kinds of crops grew well in your ancestral homelands. (Where high-yield species such as barley and rice thrive, it pays to sacrifice the immediate gains of hunting by giving over some of your territory to farming. This fosters a longer-term outlook.) Differences in gender equality around the world have their roots in whether land required a plough to cultivate – needing male strength, and relegating women to domestic tasks – or hoes and rakes, which could be used by both sexes.

More here.

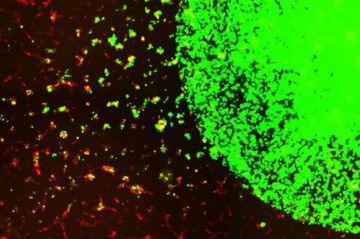

Scientists develop ‘off the shelf’ engineered stem cells to treat aggressive brain cancer

From Phys.Org:

Glioblastomas (GBMs) are highly aggressive cancerous tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Brain cancers like GBM are challenging to treat because many cancer therapeutics cannot pass through the blood-brain barrier, and more than 90 percent of GBM tumors return after being surgically removed, despite surgery and subsequent chemo- and radiation therapy being the most successful way to treat the disease. In a new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, scientists devised a novel therapeutic strategy for treating GBMs post-surgery by using stem cells taken from healthy donors engineered to attack GBM-specific tumor cells. This strategy demonstrated profound efficacy in preclinical models of GBM, with 100 percent of mice living over 90 days after treatment.

Glioblastomas (GBMs) are highly aggressive cancerous tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Brain cancers like GBM are challenging to treat because many cancer therapeutics cannot pass through the blood-brain barrier, and more than 90 percent of GBM tumors return after being surgically removed, despite surgery and subsequent chemo- and radiation therapy being the most successful way to treat the disease. In a new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, scientists devised a novel therapeutic strategy for treating GBMs post-surgery by using stem cells taken from healthy donors engineered to attack GBM-specific tumor cells. This strategy demonstrated profound efficacy in preclinical models of GBM, with 100 percent of mice living over 90 days after treatment.

More here.

Wednesday, May 18, 2022

Is Moral Expertise Possible? —A Roundtable

Geoffrey Miller, Oliver Traldi, Spencer Case, and Bo Winegard in Quillette:

Is moral expertise possible? Well, we certainly act like it is in our everyday judgments of other people. We judge some people as lacking moral expertise, insofar as we don’t expect very good moral decision-making from them, we don’t seek out their advice on moral issues, and we don’t praise them as moral role models. Such people include young children, low-IQ adults, older adults with dementia, and criminal psychopaths.

Is moral expertise possible? Well, we certainly act like it is in our everyday judgments of other people. We judge some people as lacking moral expertise, insofar as we don’t expect very good moral decision-making from them, we don’t seek out their advice on moral issues, and we don’t praise them as moral role models. Such people include young children, low-IQ adults, older adults with dementia, and criminal psychopaths.

We don’t hold our toddlers to the same moral standards as we hold our teenagers, and we don’t expect as much from our teens as we do from our work colleagues. Moral expertise develops gradually in humans, and parents take pride in any moral levelling-up that they see in their kids. In some people, moral expertise never fully develops.

More here.

Want to prevent pandemics? Stop spillovers

Neil M. Vora, Lee Hannah, Susan Lieberman, Mariana M. Vale, Raina K. Plowright, and Aaron S. Bernstein in Nature:

Spillover events, in which a pathogen that originates in animals jumps into people, have probably triggered every viral pandemic that’s occurred since the start of the twentieth century1. What’s more, an August 2021 analysis of disease outbreaks over the past four centuries indicates that the yearly probability of pandemics could increase several-fold in the coming decades, largely because of human-induced environmental changes2.

Spillover events, in which a pathogen that originates in animals jumps into people, have probably triggered every viral pandemic that’s occurred since the start of the twentieth century1. What’s more, an August 2021 analysis of disease outbreaks over the past four centuries indicates that the yearly probability of pandemics could increase several-fold in the coming decades, largely because of human-induced environmental changes2.

Fortunately, for around US$20 billion per year, the likelihood of spillover could be greatly reduced3. This is the amount needed to halve global deforestation in hotspots for emerging infectious diseases; drastically curtail and regulate trade in wildlife; and greatly improve the ability to detect and control infectious diseases in farmed animals.

More here.

The Man Who Revolutionized Computer Science With Math

[More on Leslie Lamport in Quanta here.]

Ta-Nehisi Coates on Tony Judt

Eyal Press in Public Books:

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.

That influence is the late Tony Judt, a British historian. In 2005, Judt published his magnum opus, Postwar, a sweeping, 933-page history of modern Europe.

In this conversation, which was recorded last fall, Ta-Nehisi talks about why Postwar had such a profound impact on him. He explores the preface he wrote to Ill Fares the Land, another of Judt’s books, which has just been reissued by Penguin. He also talks about the power of language to help us imagine a better world, whether he identifies as an Afro-pessimist, and what it’s like to grow up in a nationalist household.

From here.

Paradoxes Of Irrationality – Donald Davidson (1981)

Michelangelo Frammartino’s Il Buco

Anthony Hawley at Artforum:

Throughout Il Buco, most human speech—apart from that in a television feature on the Pirelli palace and the old man’s cattle calls—is only ever heard at a distance, both standard Italian and Calabrian dialects disappearing into the acoustic fabric of the film. Cinematographer Renato Berta’s camera, either suffocatingly close or slightly afield from its subjects, hastens this sensorial defamiliarization. So does the rarity of subtitles. That these only appear under two brief archival segments—the aforementioned scientific report and the Pirelli doc, viewed, in a beguiling crepuscular scene, by a mesmerized group of townspeople motionlessly watching a television plopped outside on the dirt—is to insist upon a certain incommunicability. Despite our best efforts to dominate the heavens and the underworld, some places evade epistemic capture. Murmurous soundscapes, both infinitesimal and grandiose, perplex and disorient, causing human agents and their endeavors to appear more like incidental elements in the greater chasm of time.

Throughout Il Buco, most human speech—apart from that in a television feature on the Pirelli palace and the old man’s cattle calls—is only ever heard at a distance, both standard Italian and Calabrian dialects disappearing into the acoustic fabric of the film. Cinematographer Renato Berta’s camera, either suffocatingly close or slightly afield from its subjects, hastens this sensorial defamiliarization. So does the rarity of subtitles. That these only appear under two brief archival segments—the aforementioned scientific report and the Pirelli doc, viewed, in a beguiling crepuscular scene, by a mesmerized group of townspeople motionlessly watching a television plopped outside on the dirt—is to insist upon a certain incommunicability. Despite our best efforts to dominate the heavens and the underworld, some places evade epistemic capture. Murmurous soundscapes, both infinitesimal and grandiose, perplex and disorient, causing human agents and their endeavors to appear more like incidental elements in the greater chasm of time.

more here.

After Christendom

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt at Commonweal:

Jean-Luc Marion (b. 1946) and Chantal Delsol (b. 1947) are both prominent French philosophers who are very public about their Roman Catholicism. This alone would put them, in the minds of many of their fellow citizens, into “conservative” political and cultural camps, though the truth is considerably more complicated. This past year saw the appearance in English translation of Marion’s 2017 book, A Brief Apology for a Catholic Moment, and the publication of Delsol’s La Fin de la Chrétienté. Both of these short works grapple with the role of the Church in a dechristianized culture; both show the complex negotiations required to steer between what Marion calls the “twin and rival disasters” of integralism, which seeks to establish a Christian social order, and progressivism, which risks letting any distinctively Christian identity evaporate.

Jean-Luc Marion (b. 1946) and Chantal Delsol (b. 1947) are both prominent French philosophers who are very public about their Roman Catholicism. This alone would put them, in the minds of many of their fellow citizens, into “conservative” political and cultural camps, though the truth is considerably more complicated. This past year saw the appearance in English translation of Marion’s 2017 book, A Brief Apology for a Catholic Moment, and the publication of Delsol’s La Fin de la Chrétienté. Both of these short works grapple with the role of the Church in a dechristianized culture; both show the complex negotiations required to steer between what Marion calls the “twin and rival disasters” of integralism, which seeks to establish a Christian social order, and progressivism, which risks letting any distinctively Christian identity evaporate.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Helping With Math Homework

In the beginning

there were polynomials

differences of squares

trial and error

and the sum of two cubes.

X2 minus Y2

has always had

the same meaning

whatever it is.

But when Pythagoras

looked into

the eye of a triangle

and saw the solution

I wasn’t there.

Nor have I ever found

anything more

than safety in numbers.

This is the new math

these are your problems

and I was born

before the back of the book.

What I have been saying is this:

I can lead you

only so far into wisdom.

Soon

you must begin to learn

how to be ignorant

on your own.

by John Stone

from In All This Rain

The Lost Art of Staying Put

Lucy Ellmann in The Baffler:

NOT ALL THAT LONG AGO, air travel was a clear badge of elite cultural distinction, from the “jet set” to the Sinatra-mangling ad slogan, “Come Fly With Me.” Droit-de-seigneur sexual fantasies of stewardess life were memorialized in that elegantly titled sixties tell-all Coffee, Tea, or Me? People actually used to dress up to take a plane. But that’s all over. Now you need a bulletproof vest when dealing with the cabin crew.

NOT ALL THAT LONG AGO, air travel was a clear badge of elite cultural distinction, from the “jet set” to the Sinatra-mangling ad slogan, “Come Fly With Me.” Droit-de-seigneur sexual fantasies of stewardess life were memorialized in that elegantly titled sixties tell-all Coffee, Tea, or Me? People actually used to dress up to take a plane. But that’s all over. Now you need a bulletproof vest when dealing with the cabin crew.

Airlines seem to be competing for Jerk of the Year awards. When they’re not bumping people off, figuratively or literally, they’re frighteningly “reaching out” to the customers they abused, customers with “issues.” (The language is patronizing and predatory.) We’re all sorry United’s planes are so attractive to terrorists. The staff must be under constant strain. But so are the passengers, with whom these tin-pot dictators are increasingly strict, banning leggings on ten-year-olds and bodily removing people from the passenger manifests.

Delta recruited airport police to threaten a couple with jail and the confiscation of their children, all for refusing to give up seats they’d paid for on a flight from Hawaii to LA. An American Airlines flight attendant bullied a tired mother of twin babies over her stroller, and then readied himself to punch a passenger who rose to her defense. These companies seem very exacting about how their customers behave—while apparently giving staff (or airport-based security officials) full license to unleash their inner demons. In airplane disaster movies, the pilot’s always wrestling with the yoke, trying to get full throttle; now these exertions are directed towards throttling the yokels.

More here.

“I Have to Admit, I Have a Very Low Opinion of Human Beings”

Benjamin Ehrlich in Nautilus:

In 1914, when World War I broke out, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the most influential neuroscientist in the world—the man who discovered brain cells, later termed neurons— published only one article, by far his lowest output ever. “The horrendous European war of 1914 was for my scientific activity a very rude blow,” Cajal recalled. “It altered my health, already somewhat disturbed, and it cooled, for the first time, my enthusiasm for investigation.” Cajal’s tertulia, or café social circle, was “overwhelmed with horror and abomination, erasing the last relics of our youthful optimism.” Science was supposed to be universal, but now, as mail became unreliable, telegraph lines were cut, trenches were dug, and borders were almost constantly closed, scientists could not even share their work internationally.

In 1914, when World War I broke out, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the most influential neuroscientist in the world—the man who discovered brain cells, later termed neurons— published only one article, by far his lowest output ever. “The horrendous European war of 1914 was for my scientific activity a very rude blow,” Cajal recalled. “It altered my health, already somewhat disturbed, and it cooled, for the first time, my enthusiasm for investigation.” Cajal’s tertulia, or café social circle, was “overwhelmed with horror and abomination, erasing the last relics of our youthful optimism.” Science was supposed to be universal, but now, as mail became unreliable, telegraph lines were cut, trenches were dug, and borders were almost constantly closed, scientists could not even share their work internationally.

…“I have to admit,” Cajal wrote in a new weekly newspaper, founded so that prominent intellectuals could share their views on the war, “I have a very low opinion of human beings.” As the “last hunter animal,” he wrote, we retain the “foul instincts” of beasts. “Our nerve cells continue to react in the same way as in the Neolithic Age,” he lamented. Because of “evolutionary resistance,” an “excruciating biological fact,” Cajal claimed that war will never be eradicated. All that civilization can hope to do is prolong the intervals of peace, but the “destructive phase” will always return, with each war becoming more horrifying. “In about twenty or thirty years, when the orphans of the present war will be men, the same stupendous massacre will be repeated,” he predicted with chilling accuracy. Suddenly, Cajal realized that the brain was not perfecting itself by evolution, as he had once believed. “Our descendants will be as putrid as we are,” he concluded.

More here.

Tuesday, May 17, 2022

Hernan Diaz: “I Wouldn’t Be the Person I am Without Borges.”

Jane Ciabattari at Literary Hub:

When his first novel, In the Distance, was published, Hernán Diaz described the sense of “foreignness” he gained from his formative years. He was born in Argentina; his family moved to Stockholm when he was two, and he grew up with Swedish as his first language, then relocated to Argentina when he was nine. In his twenties, he lived in London, then settled in New York.

When his first novel, In the Distance, was published, Hernán Diaz described the sense of “foreignness” he gained from his formative years. He was born in Argentina; his family moved to Stockholm when he was two, and he grew up with Swedish as his first language, then relocated to Argentina when he was nine. In his twenties, he lived in London, then settled in New York.

“Foreignness” is central to In the Distance, published by Coffee House Press in 2017, which follows Håkan Söderström as he leaves Sweden with his brother for New York during the Gold Rush. The brothers lose touch before sailing; Håkan ends up in San Francisco, and becomes determined to make his way east to find his brother. In this dangerous and challenging new land, Håkan becomes known as “The Hawk.” He is a massive fellow, apt, adventurous, solitary, ultimately legendary, able to survive no matter what threats he encounters in the frontier. Diaz’s eerie reinvention of the “Western” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, and winner of the William Saroyan International Prize, the Cabell Award, the Prix Page America, and the New American Voices Award.

More here.

The New Science of Alt Intelligence

Gary Marcus in his Substack newsletter:

For many decades, part of the premise behind AI was that artificial intelligence should take inspiration from natural intelligence. John McCarthy, one of the co-founders of AI, wrote groundbreaking papers on why AI needed common sense; Marvin Minsky, another of the field’s co-founders of AI wrote a book scouring the human mind for inspiration, and clues for how to build a better AI. Herb Simon won a Nobel Prize for behavioral economics. One of his key books was called Models of Thought, which aimed to explain how “Newly developed computer languages express theories of mental processes, so that computers can then simulate the predicted human behavior.”

For many decades, part of the premise behind AI was that artificial intelligence should take inspiration from natural intelligence. John McCarthy, one of the co-founders of AI, wrote groundbreaking papers on why AI needed common sense; Marvin Minsky, another of the field’s co-founders of AI wrote a book scouring the human mind for inspiration, and clues for how to build a better AI. Herb Simon won a Nobel Prize for behavioral economics. One of his key books was called Models of Thought, which aimed to explain how “Newly developed computer languages express theories of mental processes, so that computers can then simulate the predicted human behavior.”

A large fraction of current AI researchers, or at least those currently in power, don’t (so far as I can tell) give a damn about any of this. Instead, the current focus is on what I will call (with thanks to Naveen Rao for the term) Alt Intelligence.

Alt Intelligence isn’t about building machines that solve problems in ways that have to do with human intelligence. It’s about using massive amounts of data – often derived from human behavior – as a substitute for intelligence.

More here.

American Restlessness: Why do good fortune and prosperity leave so many of us unhappy?

Matt Dinan in The Hedgehog Review:

I am trying, in reviewing Why We Are Restless, an excellent new book by Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey, to keep myself out of it. My usual essayistic approach, I fear, will lead a reader to think that I object to the book’s diagnosis of what went wrong with the modern world more than I do. Besides, the tendency of critics to involve themselves in their reviews is irritating, and surely an example of the type of Montaignean introspection that may well be making us restless. But Why We Are Restless stands out among other books like it by answering the question implied by its title with rigor and charity, by (mostly) succeeding in presenting the view it contests “in terms of the most decent human aspirations.” Cataloguing one’s own restlessness, or subjecting readers to one’s bargain-bin Tocquevillian observations about the United States of America, would veer dangerously into the Montaignean territory here scrutinized. I will make an attempt (essai), in other words, to share some thoughts (pensées) about this fine book.

I am trying, in reviewing Why We Are Restless, an excellent new book by Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey, to keep myself out of it. My usual essayistic approach, I fear, will lead a reader to think that I object to the book’s diagnosis of what went wrong with the modern world more than I do. Besides, the tendency of critics to involve themselves in their reviews is irritating, and surely an example of the type of Montaignean introspection that may well be making us restless. But Why We Are Restless stands out among other books like it by answering the question implied by its title with rigor and charity, by (mostly) succeeding in presenting the view it contests “in terms of the most decent human aspirations.” Cataloguing one’s own restlessness, or subjecting readers to one’s bargain-bin Tocquevillian observations about the United States of America, would veer dangerously into the Montaignean territory here scrutinized. I will make an attempt (essai), in other words, to share some thoughts (pensées) about this fine book.

More here.

Bertrand Russell on his meeting with Vladimir Lenin in 1920

And the rest of the whole interview with John Chandos from 1961:

Tuesday Poem

The Cupboard

broken glass is held together

with bits and pieces

of an old yellowed newspaper

each rectangle

of the doorframe

is an assemblage

insecure setsquares of glass

jagged slivers thrusting down

precarious trapeziums

the cupboard is full

of shelf upon shelf

of gold gods in tiny rows

you can see the golden gods

beyond the strips

of stock exchange quotations

they look out at you

from behind slashed editorials

and promises of eternal youth

you see a hand of gold

behind opinion

stiff with starch

as one would expect

there is naturally

a lock upon the door

by Arun Kolatkar

from Jejuri

New York Review Books, 1974

Very Cold People – chilly legacy of abuse

Lauren Elkin in The Guardian:

Well into a career that encompasses poetry, memoir and projects such as her 2017 collection of quotable fragments 300 Arguments, the American author Sarah Manguso has turned to the novel. Very Cold People is also composed of short sections, compiled like witness testimony by a young girl called Ruthie, as she grows up in the fictional town of Waitsfield, Massachusetts, somewhere near Boston. Ruthie and her family don’t belong there, she tells us in the first sentence; it is a town for people whose ancestors came over with the pilgrims to settle in that violently snowy part of the new world.

Well into a career that encompasses poetry, memoir and projects such as her 2017 collection of quotable fragments 300 Arguments, the American author Sarah Manguso has turned to the novel. Very Cold People is also composed of short sections, compiled like witness testimony by a young girl called Ruthie, as she grows up in the fictional town of Waitsfield, Massachusetts, somewhere near Boston. Ruthie and her family don’t belong there, she tells us in the first sentence; it is a town for people whose ancestors came over with the pilgrims to settle in that violently snowy part of the new world.

The very cold people of the title refers not only to the inhabitants of this icy region, but to Ruthie’s own parents. At the outset they seem merely bohemian and thrifty, buying her toys secondhand and her clothes at factory outlets, but then we hear about Ruthie’s mother dredging a fancy wristwatch catalogue out of the dump, ironing its crumpled cover and displaying it on the coffee table, “just askew […] as if someone had been reading it and carelessly put it down, and she corrected its angle when she walked by”. This is something more than parsimony and closer to a pathological need, in the face of material want, to be perceived in a certain way – as offhandedly rich, casual. Her mother, the victim in her youth of some unspecified assault, “was the protagonist of everything”; Ruthie recalls being told of her own birth: “the doctor said Oh she’s beautiful […] and my mother had thought he was talking about her”.

More here.