Morten Høi Jensen in Liberties:

Pity literary biographers. There are few writers less appreciated, there are none more despised. There they sit, with their church bulletins of family trees and their dental records, their interviews with ex-lovers, mad uncles, and discarded children, and go about “reconstructing” the life of someone they never knew, or knew just barely. To George Eliot, biographers were a “disease of English literature,” while Auden thought all literary biographies “superfluous and usually in bad taste.” Even Ian Hamilton, the intrepid chronicler of Robert Lowell, J. D. Salinger, and Matthew Arnold, thought that there was “some necessary element of sleaze” to the whole enterprise.

Pity literary biographers. There are few writers less appreciated, there are none more despised. There they sit, with their church bulletins of family trees and their dental records, their interviews with ex-lovers, mad uncles, and discarded children, and go about “reconstructing” the life of someone they never knew, or knew just barely. To George Eliot, biographers were a “disease of English literature,” while Auden thought all literary biographies “superfluous and usually in bad taste.” Even Ian Hamilton, the intrepid chronicler of Robert Lowell, J. D. Salinger, and Matthew Arnold, thought that there was “some necessary element of sleaze” to the whole enterprise.

And yet biographies of writers continue to excite the reading public’s imagination. Last year alone saw big new accounts of the lives of W. G. Sebald, Fernando Pessoa, Philip Roth, Tom Stoppard, D. H. Lawrence, Elizabeth Hardwick, H.G. Wells, Stephen Crane, and Sylvia Plath. The most controversial of these, of course, was Blake Bailey’s biography of Roth, which was withdrawn by its publisher just a few weeks after it appeared owing to accusations against Bailey of sexual assault and inappropriate behavior.

More here.

Both countries are English-speaking democracies with similar demographic profiles. In Australia and in the United States, the

Both countries are English-speaking democracies with similar demographic profiles. In Australia and in the United States, the  In 2005, Britain’s then–Labour chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, chose the backdrop of Tanzania to make a dramatic statement about his nation’s unmatched record of imperial conquest and rule. “The time is long gone,” he said, “when Britain needs to apologize for its colonial history.” The choice of locale for such a proclamation was, to be charitable, curious. A braver stage would have been Kenya, to pick an African nation that had experienced horrific violence during its independence struggle from British colonial rule, or India or Malaya, where extreme and brutal measures to sustain imperial control had been carried out on an even greater scale. But here we were, nonetheless.

In 2005, Britain’s then–Labour chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, chose the backdrop of Tanzania to make a dramatic statement about his nation’s unmatched record of imperial conquest and rule. “The time is long gone,” he said, “when Britain needs to apologize for its colonial history.” The choice of locale for such a proclamation was, to be charitable, curious. A braver stage would have been Kenya, to pick an African nation that had experienced horrific violence during its independence struggle from British colonial rule, or India or Malaya, where extreme and brutal measures to sustain imperial control had been carried out on an even greater scale. But here we were, nonetheless. Apparently Anna Wintour wants to be seen as human, and Amy Odell’s biography goes some way to helping her achieve that aim. Nearly all the photographs show her smiling, looking friendly, even girlish. And the text quite often mentions her crying. On 9 November 2016 she cried in front of her entire staff because Hillary Clinton lost the election. But then she immediately set about trying to persuade Melania Trump to do a Vogue shoot. Melania, another tough cookie, refused unless she was guaranteed the cover.

Apparently Anna Wintour wants to be seen as human, and Amy Odell’s biography goes some way to helping her achieve that aim. Nearly all the photographs show her smiling, looking friendly, even girlish. And the text quite often mentions her crying. On 9 November 2016 she cried in front of her entire staff because Hillary Clinton lost the election. But then she immediately set about trying to persuade Melania Trump to do a Vogue shoot. Melania, another tough cookie, refused unless she was guaranteed the cover. These are strange times for the Indigenous Nenets reindeer herders of northern Siberia. In their lands on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, bare tundra is thawing, bushes are sprouting, and willows that a generation ago struggled to reach knee height now grow 3 meters tall, hiding the reindeer. Surveys show the Nenets autonomous district, an area the size of Florida, now has four times as many trees as official inventories recorded in the 1980s. In some places the trees are advancing along a wide front, but in other places the gains are patchier, says forest ecologist Dmitry Schepaschenko of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who has mapped the greening of the Siberian tundra. “A few trees appear here and there, and some shrublike trees become higher.”

These are strange times for the Indigenous Nenets reindeer herders of northern Siberia. In their lands on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, bare tundra is thawing, bushes are sprouting, and willows that a generation ago struggled to reach knee height now grow 3 meters tall, hiding the reindeer. Surveys show the Nenets autonomous district, an area the size of Florida, now has four times as many trees as official inventories recorded in the 1980s. In some places the trees are advancing along a wide front, but in other places the gains are patchier, says forest ecologist Dmitry Schepaschenko of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who has mapped the greening of the Siberian tundra. “A few trees appear here and there, and some shrublike trees become higher.” There is a scene in Fox’s 1930 comedy So This Is London in which Hiram Draper, played by Will Rogers, attempts to get a passport. When Hiram is unable to provide a birth certificate, the passport-office official inquires if he is an American citizen. Rogers, in his thick Oklahoman accent, responds: “I think I am. My folks are Indian. Both my mother and father had Cherokee blood in ’em. Born and raised in Indian Territory. Of course, I’m not one of these Americans whose ancestors come over on the Mayflower, but we met ’em when they landed.” It’s a great bit of comedy, a pre-Code jab pointing out an existential absurdity of America itself. It’s also a key to Rogers’s brand of humor and his positioning as a straight-talking outsider lodged in the eye of popular culture’s storm.

There is a scene in Fox’s 1930 comedy So This Is London in which Hiram Draper, played by Will Rogers, attempts to get a passport. When Hiram is unable to provide a birth certificate, the passport-office official inquires if he is an American citizen. Rogers, in his thick Oklahoman accent, responds: “I think I am. My folks are Indian. Both my mother and father had Cherokee blood in ’em. Born and raised in Indian Territory. Of course, I’m not one of these Americans whose ancestors come over on the Mayflower, but we met ’em when they landed.” It’s a great bit of comedy, a pre-Code jab pointing out an existential absurdity of America itself. It’s also a key to Rogers’s brand of humor and his positioning as a straight-talking outsider lodged in the eye of popular culture’s storm. Howe’s latest book, London-rose: Beauty Will Save the World, is a strange, changeable artifact. As does much of her work, it luxuriates in formal and generic plasticity: it is not poetry, exactly, but nor is it precisely prose. London-rose might be more usefully regarded as a consortium of fragments—historical apocrypha, lists, philosophic and monastic citations, and other ephemera—which are loosely gathered in the folds of a skeletal plot concerning an unnamed and structurally anonymized female pencil pusher. Howe called 2020’s Night Philosophy her “last” book, and to give credit where it is due, London-rose isn’t technically “new.” The manuscript is traceable in some form to the early 1990s, the decade during which Howe was in the thick of a sequence of five novels she has said are as near to a personal biography as she wishes to get. (They were collected in an omnibus as Radical Love by Nightboat in 2006, and the last of them—Indivisible—is being reissued in tandem with the publication of London-rose.)

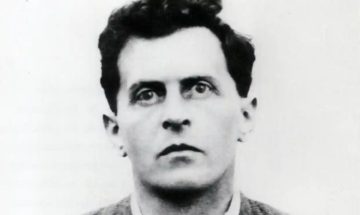

Howe’s latest book, London-rose: Beauty Will Save the World, is a strange, changeable artifact. As does much of her work, it luxuriates in formal and generic plasticity: it is not poetry, exactly, but nor is it precisely prose. London-rose might be more usefully regarded as a consortium of fragments—historical apocrypha, lists, philosophic and monastic citations, and other ephemera—which are loosely gathered in the folds of a skeletal plot concerning an unnamed and structurally anonymized female pencil pusher. Howe called 2020’s Night Philosophy her “last” book, and to give credit where it is due, London-rose isn’t technically “new.” The manuscript is traceable in some form to the early 1990s, the decade during which Howe was in the thick of a sequence of five novels she has said are as near to a personal biography as she wishes to get. (They were collected in an omnibus as Radical Love by Nightboat in 2006, and the last of them—Indivisible—is being reissued in tandem with the publication of London-rose.) Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!”

Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!” There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

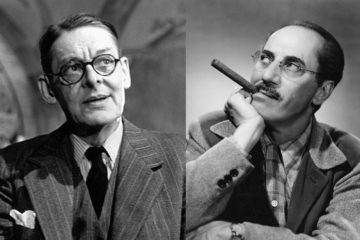

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away.

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away. S

S