Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World:

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World:

In 1959, the leaders of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC, now the OECD) appointed a Group of Independent Experts “to study the experience of rising prices” in the recent history of the advanced capitalist countries. Between the end of World War II and the termination of the Korean War conflict, economic planners had tolerated rising prices as an insurmountable consequence of postwar reconstruction and war-induced commodity speculation. These governments expected inflation to end as economies readjusted following the stalemate in Korea. “In the event, however,” the Group of Independent Experts wrote in their final report, “rising prices proved to be a continuing problem.”

The OECD report classified four causes to the inflation of the 1950s: rising wages, monopolistic pricing, excess demand, and what they called “special prices”—those influenced, for example, by foreign governments, bad harvests, or the lifting of government price controls.

At a moment when inflation control is back on the agenda, it is worth observing just how little consensus existed—during a period remembered for its supposed social cohesion and intellectual conformity—on these ostensibly technical concerns. By 1961, when the study group released its final report, its members were not even able to agree on concrete findings regarding the causes of inflation.

More here.

I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is

I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is  Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language.

Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language. It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.”

It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.” A

A  From the Dynomight blog:

From the Dynomight blog:  Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements.

Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements. The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been

The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been  After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic.

After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic. Imagine there were no Beatles—or that there was no Beatlemania anyway and that the lads from Liverpool were just another band that never got a record deal or that split up before they hit it big. That is the premise Harvard University professor

Imagine there were no Beatles—or that there was no Beatlemania anyway and that the lads from Liverpool were just another band that never got a record deal or that split up before they hit it big. That is the premise Harvard University professor  On the back cover of Tariq Ali’s new book on Winston Churchill, a less flattering and so less familiar portrait of the wartime icon comes into view. Here, the man voted the Greatest Briton ever by over a million of his compatriots in 2002 fulminates against everything from women’s suffrage and liberal causes to “international Jews,” “uncivilised tribes” and “people with slit eyes and pigtails.” Ali also alludes to Churchill’s approval of the Conservative slogan “Keep England White”—at the same time MPs like Fenner Brockway were bringing the Race Discrimination Bill to parliament—and includes an extract from the cringeworthy praise he heaped on Mussolini in 1927. Such pronouncements will not be new to anyone familiar with the subject, but to invoke them in rarefied British company is usually to elicit the dismissive claim that they are not representative of Churchill or that they were simply “of their time.” “Nobody’s perfect” goes the more casual response, as if a view of the world in which Anglo-Saxons were “a higher grade race” entitled to rule the rest was simply a charming upper-class foible.

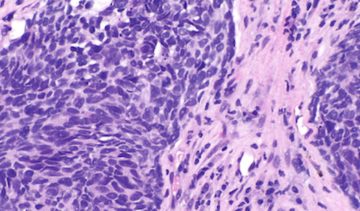

On the back cover of Tariq Ali’s new book on Winston Churchill, a less flattering and so less familiar portrait of the wartime icon comes into view. Here, the man voted the Greatest Briton ever by over a million of his compatriots in 2002 fulminates against everything from women’s suffrage and liberal causes to “international Jews,” “uncivilised tribes” and “people with slit eyes and pigtails.” Ali also alludes to Churchill’s approval of the Conservative slogan “Keep England White”—at the same time MPs like Fenner Brockway were bringing the Race Discrimination Bill to parliament—and includes an extract from the cringeworthy praise he heaped on Mussolini in 1927. Such pronouncements will not be new to anyone familiar with the subject, but to invoke them in rarefied British company is usually to elicit the dismissive claim that they are not representative of Churchill or that they were simply “of their time.” “Nobody’s perfect” goes the more casual response, as if a view of the world in which Anglo-Saxons were “a higher grade race” entitled to rule the rest was simply a charming upper-class foible. “No cancer patient should die without trying immunotherapy” is a refrain in oncology clinics across the country right now. A treatment consisting of antibodies that awaken the immune system to attack cancer, immunotherapy carries far more promise than chemotherapy, and it has considerably fewer side effects. Since the FDA’s first approval a decade ago, it has revolutionized cancer care. Consider Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Twenty years ago, when the only option was chemotherapy, oncologists could tell their patient, with almost 100 percent certainty, that they would not be alive in two years. Today, miraculously, many patients with Stage IV lung cancer are alive five years after diagnosis — and some are even cured.

“No cancer patient should die without trying immunotherapy” is a refrain in oncology clinics across the country right now. A treatment consisting of antibodies that awaken the immune system to attack cancer, immunotherapy carries far more promise than chemotherapy, and it has considerably fewer side effects. Since the FDA’s first approval a decade ago, it has revolutionized cancer care. Consider Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Twenty years ago, when the only option was chemotherapy, oncologists could tell their patient, with almost 100 percent certainty, that they would not be alive in two years. Today, miraculously, many patients with Stage IV lung cancer are alive five years after diagnosis — and some are even cured. In recent weeks, I spoke with nearly two dozen people in, adjacent to, and critical of the crypto space about what they envision to be the purpose of crypto. What emerged was a picture that was simultaneously murky and clarifying, in that there’s not one good answer. Some of what it does is promising; a lot of what it does — even boosters admit — is trash, and trash that’s costing some people a lot of money. This probably isn’t the death knell for crypto — it’s gone through plenty of boom and bust cycles in the past. It would be unwise to definitively say that crypto has no chance of being a game changer; it would also be disingenuous to claim it is now.

In recent weeks, I spoke with nearly two dozen people in, adjacent to, and critical of the crypto space about what they envision to be the purpose of crypto. What emerged was a picture that was simultaneously murky and clarifying, in that there’s not one good answer. Some of what it does is promising; a lot of what it does — even boosters admit — is trash, and trash that’s costing some people a lot of money. This probably isn’t the death knell for crypto — it’s gone through plenty of boom and bust cycles in the past. It would be unwise to definitively say that crypto has no chance of being a game changer; it would also be disingenuous to claim it is now.